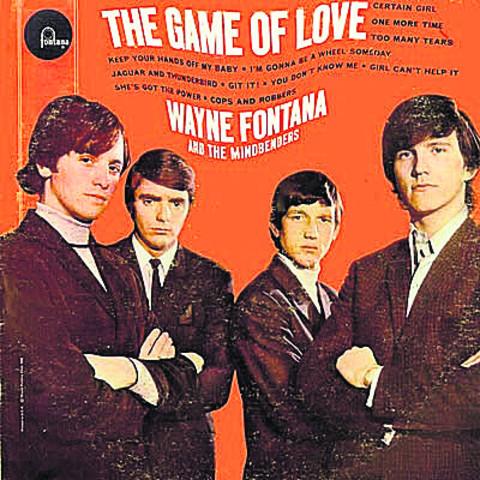

‘Extraordinary how potent cheap music is.” Noël Coward’s memorable observation (from Private Lives) came naturally to mind last Thursday as I watched the matinée performance of Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing at Oxford Playhouse. Like his later hit Rock ’n’ Roll, the play makes significant use of pop music. This is not, as in Rock ’n’ Roll, of the variety we used to style ‘progressive’ (by the likes of The Doors, The Velvet Underground, and Pink Floyd and its flawed creative genius Syd Barrett) but cheesier offerings from, among others, Herman’s Hermits, The Monkees and Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders (that’s Wayne above).

Having said that, we did get to hear Procol Harum’s A Whiter Shade of Pale, a song so perfect that John Lennon, riding round London listening to it over and over again on the tape deck of his psychedelically painted Rolls-Royce Phantom, determined that The Beatles must try to match it. (Personally, I always preferred their follow-up, Homburg.) A Whiter Shade of Pale inspires one of the The Real Thing’s better jokes when its musically ignorant playwright hero Henry (closely modelled, of course, on Stoppard himself) suggests Bach has ripped off its tune for his Air on a G String. The best joke, I thought, related to another of the great Bs: “If Beethoven had been killed in a plane crash at 22, the history of music would have been very different. As would the history of aviation, of course.”

One aspect of music’s potency is its capacity to transport us through time. Just a snatch or two of a song can remind us of where we were and what we were doing when we first heard it.

At the time of the mid-sixties music celebrated in The Real Thing, I was an arrogant schoolboy with what I considered sophisticated tastes. Wayne Fontana’s The Game of Love and Um, Um, Um, Um, Um, Um were defintely not for me. Stoppard has some fun at the expense of the second named hit. These really were the days of daft titles, as seen in Manfred Mann’s Do Wah Diddy Diddy and the Small Faces Sha-La-La La-Lee. At least there was no risk of an accidental mishearing as was the case, say, with Herman’s Hermits’ She a Must to Avoid, which I (and others) originally thought was “She’s a muscular boy”.

By ‘others’ I mean my schoolmates, some of whom were strongly in my mind recently. This was as a consequence of a meeting I fixed up with one of our old masters, a gentleman whom I had not clapped eyes on for 43 years.

Coming across his name in a recent biography of Boris Johnson, I contacted its author (a friend of a friend) who was able to give me his address.

We exchanged a couple of letters and two weeks ago, during a visit to his old Oxford college, my mentor (as in some respects I regard him) joined me for lunch in my local pub, The Punter, the scene of my meeting a few weeks earlier with David Cameron (I regret the disappointment felt by some readers over the delayed publication of photographs of that historic event).

The occasion turned out to be a very happy one, with much discussed about what had befallen us in the half-lifetime and more since our last meeting.

“The years are of no consequence” were the closing words of the letter he had sent in reply to my first approach. It certainly seemed so to me, seated opposite the same wise and witty companion who looked not dissimilar in his mid-sixties from the way he looked in his twenties.

What he must have thought about me, though, is a different matter. The child he drove on a first visit to the Oxford Playhouse aged 15 had become a whiskery old man. A bald pate replaced the luxuriant curls of my youth.

He, it turned out, well remembered my appearance from those days. In one of the slides he showed to generations of schoolboys studying architectural history at Eton, I was to be seen standing in front of the Temple of the Winds at Castle Howard — a relic of one of my childhood trips with him.

Was David Cameron among them? Hard to say. As my friend wrote: “You are rarely privileged to be remembered by me so clearly. When I was phoned up [by the Boris biographer] about D. Cameron, I protested that I’d never taught him, only to be shown that I’d taught him a good deal (ie, for a good deal of time) and in his final A-level year at that. Still, I have no memory of him at all.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here