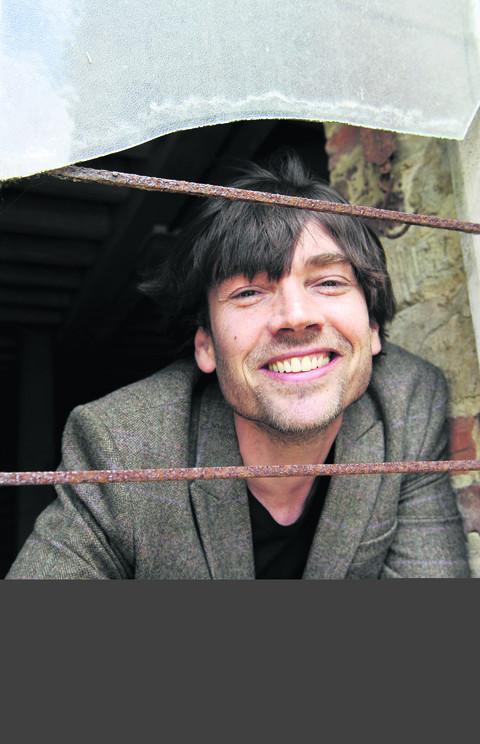

The transformation of Alex James from hell-raising rock star to farmer and cheesemaker has been well chronicled in the journalism that has proved to be a third area of expertise for this versatile man.

Let me at once mention a fourth, fatherhood, he and wife Claire having a brood of five children — sizeable by any standards — with whom they share their life on a 200-acre property at Kingham.

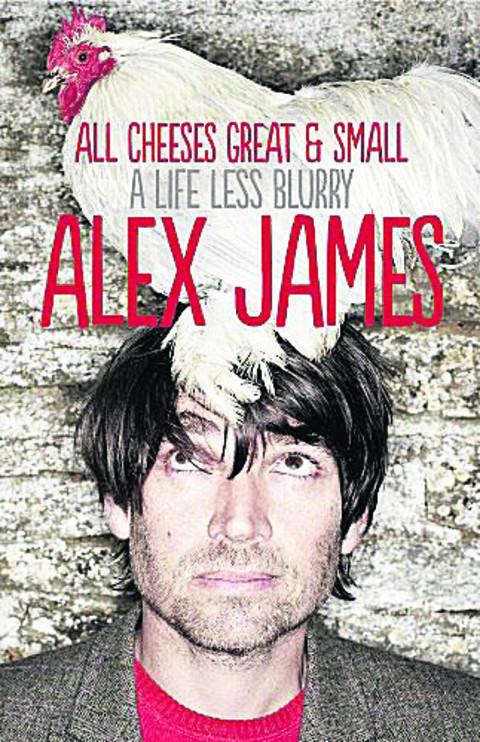

Something of the change in lifestyle experienced by Blur’s bass guitarist was chronicled in the later pages of his biography, A Bit of a Blur, which came out in 2007. Now we are told far more — and very entertainingly — in James’s second book, All Cheeses Great & Small: A Life Less Blurry (4th Estate, £16.99).

Though it is not spelt out in this adroit, well-expressed memoir, I think it can be assumed that the ‘cheeses’ of the title relates as much to the human as to the edible varieties.

The arrival of the Jameses in Kingham nine years ago slightly predated events that were to transform it into a much-commented-upon outpost of the Chipping Norton set.

These included the opening by Emily Watkins of The Kingham Plough, with its many culinary wonders, and the development into a highly-fashionable venue of Carole Bamford’s shop and restaurant at Daylesford Organic. Both these made a major contribution to Kingham’s being named Britain’s best place to live by Country Life magazine.

Forbes magazine was later to even things up for rival Burford, though it has always seemed to me more a place to gaze upon admiringly than live in.

All these matters are described, names in place, by James. The principal figures in the Chippy Set are absent, however. This includes the greatest cheese of all, David Cameron, who will often have crossed our author’s path.

That Alex has made significant inroads into the world of the aristocracy (and, indeed, of much newer money) is obvious from the occasional mention of such as the Duke and Duchess of Somerset and another magnate obstinately — and rather comically — incapable of remembering our hero’s name, despite their repeated meetings.

No less comical to me was the second sentence on page 250 from a James who is now clearly way up the social ladder: “We were going to Daphne’s to shoot grouse.” To one of my generation, mindful of the ‘grouse moor’ image that was said to make Harold Macmillan and his ilk so hopelessly out of touch, it is remarkable to ponder that these types live on into the 21st century.

Years ago, in his days stacking shelves at Safeway, could James have foretold the remarkable trajectory of his career?

Finally, lest he damage his reputation at the local pubs he so much enjoys, I should point out that the “different shaped sticks” he believe figure in Aunt Sally would not go down well with most Oxfordshire players.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here