What a glorious weekend it was! And as the sun shone, Rosemarie and I headed off with two friends for a day and a half in Great Malvern. While it was good to be away, we found the city we had left behind could not be forgotten long.

We travelled there in great style by train, enjoying smoked salmon sandwiches and champagne in a virtually empty carriage as our InterCity 125 zipped through the Cotswold countryside. Having secured a group booking, we paid just £15 each for return fares.

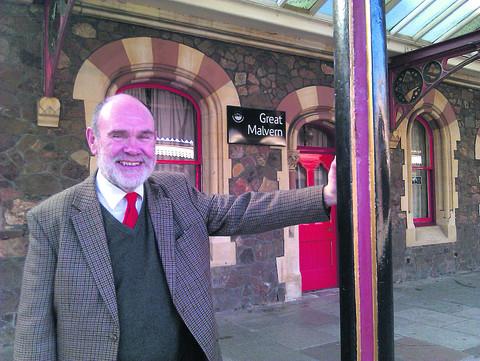

Arrival at Great Malvern’s lovely station (E.W Elmslie, 1862), with its gaily painted pillar capitals, brought our first encounter with a historical figure who would become familiar in the hours ahead. Lady Emily Foley, her name commemorated in the tearooms there, was a key sponsor in the building of the station and, indeed, of so much else in Great Malvern. A daughter of the Duke of Montrose and widow of the local squire, Edward Foley, she was largely responsible, through judicious sale of land, for Great Malvern’s development as a spa resort. Though I did not realise it as we walked up from the station to the town centre, the large Victorian properties we passed — “like a village of vicarages,” I observed — were the product of her ruling that allowed the building of only one house per acre, which had to be surrounded by trees.

Our bags stowed at the Great Malvern Hotel, we set off in search of a drink, then lunch. First, though, I had a haircut, in Burley’s, on Worcester Road, its decor unchanged since the 1960s reminding me of the salons of my childhood. As he gave me a number two trim, David Burley told me of his days as official barber to Malvern College when the teenage Jeremy Paxman and Tim Henman’s two brothers (though not Tim himself) were among his clients. I felt obliged to mention that I had met all three in Oxford.

By now, my companions were enjoying the sunshine (and a spectacular view over the Severn Plain) from the terrace of the Foley Arms Hotel. Here there was lots more to learn (such is owner J.D. Wetherspoon’s commendable respect for history) about the redoubtable Lady Emily, for whom of course it was named.

I thought it so fitting that she should have died, aged 94, as the bells were ringing in January 1, 1900. Such a quintessentially Victorian figure (she dined attended by four footmen and built two new churches in Great Malvern to preserve the Priory for the toffs) clearly had no place in the egalitarian 20th century.

The writers and Oxford dons J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis — regular visitors to Malvern — also feature prominently in the hotel’s historical memorabilia. So does the Oxford poet W.H. Auden, who taught nearby.

Across the road at The Unicorn pub, where we went for lunch, we heard more about Lewis and Tolkien from landlady Sue. Lewis especially, she felt, would have supplied the necessary christian antidote to black magician Aleister Crowley, the self-styled Great Beast 666, who was another frequent visitor.

Lewis and Tolkien, famous for their love of beer, would surely have relished the variety available today at what is, after the Priory, Great Malvern’s oldest building. Brain’s, Doom Bar and Greene King London Glory were all much enjoyed.

Even as I pointed this out, I heard the name of the pair’s favourite Oxford pub, the Eagle and Child, emerge from a group clustered at the bar. Soon there was mention, too, of The Grapes in George Street, whose reopening I shall have attended before this is read.

“There are some chaps who clearly know Oxford,” I said — at which point one of them strode over and asked: “Aren’t you Mr Gray?” There could in the circumstances be only one answer. “I came to service your boiler last year,” he added. “Did you remember to get that outlet pipe fixed?”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here