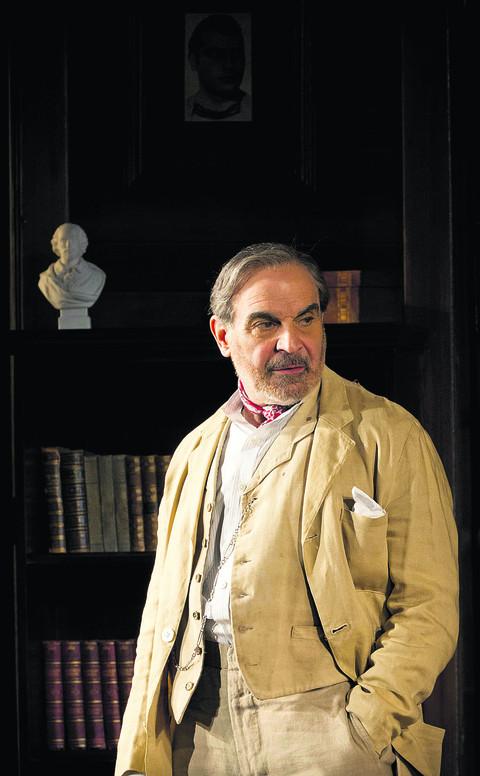

David Suchet’s portrait of the richly talented but fatally flawed James Tyrone in Eugene O’Neill’s dark autobiographical drama Long Day’s Journey into Night proves to be another triumph for this popular and charismatic actor. In Milton Keynes this week on its way to a West End run, the production looks set to garner for Suchet plaudits to rival those he enjoyed two years ago in Arthur Miller’s All My Sons.

The revival, under director Antony Page, could in one sense be considered centennial, since 1912 is the setting for the action, all of it with a solid basis in reality. The play — written 30 years after the events set down “in tears and blood,” as O’Neill expressed it — presents a day in the life of the writer at home among a family clearly making — as Tolstoy might have it — its own unique stab at unhappiness.

Presiding over the discord and discontent is paterfamilias James, a portrait of O’Neill’s father, an Irish immigrant who achieved fame on the American stage. Outwardly cheery in their gimcrack summer house by the sea (designer Lez Brotherston), he turns out to be wrestling with twin demons of alcoholism and low self-worth. Tight-fistedness — not considered characteristic of the Irish — is a problem, too, at least for his wife and sons.

Like Joe Keller in All My Sons, Tyrone is a man who has made ‘one big mistake’. Not until significant inroads have been made into a series of whisky bottles, do we learn what this is.

Like Keller, too, he possesses a wife who obstinately blinds herself to reality concerning one of her offspring. Mary Cavan Tyrone (Laurie Metcalf) speaks of her younger son Edmund (O’Neill himself) as suffering from a “summer cold” when it is obvious to all that his condition is much more serious.

Her self-delusion is as much an incurable aspect of her character as her distressing addiction to morphine. That nothing can change — in O’Neill’s view at least — is the most lowering aspect of the play. “The past is the present, it is the future, too,” we are told.

There is consolation, though, in that one ‘character’ — as we know — will go on to survive that upbringing, the envy and enmity of an alcoholic elder brother (Trevor White) and the tuberculosis, to become the greatest playwright of his age.

Something of the genius to come is apparent in the poetry of lines O’Neill gives to ‘himself’ — particularly on the subject of his beloved sea — and which are sensitively delivered here by Kyle Soller. Inspired, no doubt, by the subtle, beautifully spoken performances of Suchet and Metcalf, Soller — a memorable Tom Ripley at Northampton a while since — is making a clear bid here (as other Edmunds have before him) to become a big-name star. I think it probable he will succeed.

At Milton Keynes Theatre until Saturday. Apollo Theatre, London, from April 2.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article