One of the most original and compelling of England’s 20th- century artists, Graham Sutherland (1903-1980) has been rather neglected in recent decades. An exemplary show at Modern Art Oxford of more than 80 rarely seen works on paper — early Welsh landscapes from the 1930s, works as an official Second World War artist, and after return to Pembrokeshire in the 1970s — reminds us why he was a leading figure in post-war British art.

Graham Sutherland: An Unfinished World is curated by a contemporary painter: 2011 Turner Prize nominee George Shaw, whose own works of deserted urban landscapes reflect the post-war Coventry council estate he grew up on. Sutherland had strong links to Coventry. Shaw traces his interest in Sutherland to his boyhood, recalling that the new cathedral was “like an art gallery” inside which “hung Sutherland’s monstrous tapestry”. Sutherland’s paintings are “a lament to the passing and changing landscape, a monument to the earth itself,” he says, and Sutherland “an artist as much rooted in the past as in the world before him — a world forever unfinished”.

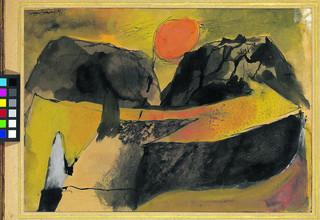

Arranged chronologically, the show begins and ends with two extraordinary paintings: a watercolour of 1937, Sun Setting Between Hills, and Twisting Roads, a 1976 watercolour, gouache and chalk. Stand in the middle of the opening room and you see both at once. They have a lot in common; undated, it would be hard to tell which came first. In the earlier, an orange sun clings drunkenly to a gash in the hills, a dotted line connecting it to standing stones, and a giant slash of yellow road gouges its way across the landscape, like a jagged arrow pointing out of the picture. In the later, things are more cursive, bar geometric man-made structures sitting silently by, and a mournful green sun weeps its sunbeams from a pitch black sky. Twisting Roads is the less edgy, but both are dramatic.

Sutherland felt the intrinsic drama of the Welsh landscape from the moment he first visited Pembrokeshire in 1934. “The clear, yet intricate construction of the landscape coupled with an emotional feeling of being on the brink of some drama . . .” influenced him profoundly.

He was exhilarated by the “exultant strangeness” of what he saw — and you needn’t go far into this show to see Sutherland’s great capacity to convey that in paint.

His titles are down-to-earth, however, unemotional: Landscape with Mounds; Earth Removed from Coal. The titles of his Devastation series of 1941, painted when an official war artist — hung in the impressive third gallery together with emotive mining images — baldly record the destruction wreaked by war: City, Twisted Girders; Fallen Lift Shaft; East End, Burnt Paper Warehouse; Collapsed Roof. In contrast, his interpretations of this destruction have a dark disquieting, yet exciting beauty.

A few of Sutherland’s spiky anthropomorphised trees and stumps, interlocking and anguished, painted in acid shades, shown in a small side room form a colourful counterpoint to the predominant sulphurous yellows, greys and blacks in this electrifying show.

A shot in the arm for Sutherland fans and a thrilling introduction to those previously unfamiliar with his work, it is on at MAO until March 18, 2012.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article