Funny how over centuries quaint customs flourish, wither, and then flourish again in slightly different form. Take St Valentine’s Day for instance.

In the early 19th century commercially produced cards, such as some of us received or sent this week, were widely available; but by the end of that century they had fallen into disrepute, only to be revived again during the Second World War when American servicemen re-imported the custom — and card manufacturers took it up with gusto.

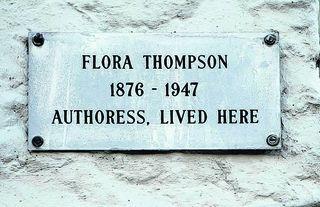

But during the period about which Flora Thompson (1876-1947) was writing in her Lark Rise to Candleford — concerning the goings-on in the North Oxfordshire village of Juniper Hill (Lark Rise in the book) and nearby Candleford — the true Valentine spirit was already all but dead, surviving only in a cynical sort of way in the shape of a surprisingly large number of offensive mock Valentine cards passing through even the most rural of post offices.

Lark Rise heroine Laura (a thinly disguised version of the author) picked one out of the box at the post office in which she worked at Candleford Green (Fringford). It was addressed to her and was immediately consigned to the fire. It featured a picture of a hideous woman selling stamps with a caption that began: “You think yourself so la-di-da/And get yourself up so grand” — and then advised her to wear a veil whenever she went out so as not to frighten the cows.

And yet that part of Oxfordshire, bordering Northamptonshire, had until 30 years or so previously, enjoyed a particularly strong and genuine Valentine spirit. Not only did real cards, both home-made and printed, get sent out but children also went “valentining” from house to house singing “Good morrow, Valentine”.

But so moribund was the true spirit of St Valentine’s Day during the 1890s that the Graphic magazine reported on February 17, 1894: “St Valentine’s Day . . . attracts very little attention nowadays in England, but across the Atlantic the Saint is still honoured.”

As a matter of fact, though, the one thing that is certain about the whole Valentine habit is that St Valentine himself had nothing to do with the various traditions that have grown up around his day. Almost nothing is known of him except that he was one of many with that name and that he was martyred during the reign of the Roman emperor Claudius in about 270 AD. Some say he was buried on February 14 in the Via Flaminia, north of Rome.

But he had nothing to do with romance, or spring, or birds, or even the Roman feast of Lupercalia with which many later writers have tried to associate him. It seems that his day just happened to coincide with a convenient date for celebrating the earliest signs of spring.

The Romantic side of St Valentine’s Day really begins with three 14th-century poets: Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400), whose son Thomas had houses at both Woodstock and Ewelme; his friend John Gower (1330-1408), whose patron was Duke Humfrey of Gloucester, who bequeathed his books to Oxford University; and the soldier poet John Clanvowe (1341-1391) whose grave was discovered in 1913 in Istanbul.

Chaucer’s poem Parliament of Foules tells how birds choose their mates on St Valentine’s Day; Gower’s poem (in French) Cinkante Ballades uses the same theme; and so does Clanvowe’s The Cuckoo and the Nightingale — and it seems that all three were drawing on an earlier tradition.

By the 17th century, Valentine celebrations had evolved into a lively sort of ritualistic game — as described by that frequent visitor to Oxford and Oxfordshire, Samuel Pepys. He refers to Valentine more than 20 times in his diaries between 1660 and 1669. It seems that by then the rules of the game left everything to Fate. Names were written on scraps of paper, lots were drawn, and couples were paired off accordingly.

Each then paid the other little compliments, including the men buying small presents for the girls, for the next few days. Even married people like Samuel and Elizabeth Pepys joined in the game; and adults often made pretend Valentines of friends’ children. (Not that Pepys let that stop him from referring, cynically, to at least one of his real-life mistresses as his “Valentine”).

Mrs Pepys also believed that on St Valentine’s Day she ran the risk of falling in love with the first half-way presentable man upon whom she clapped eyes. She therefore spent the morning of February 14, 1662, blindfolded.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article