The setting is the upper library, stacked high with ancient volumes, of a grammar school in Stockport. This is the domain — away from hoi polloi in the common room — of a group of A-level pupils who appear to regard themselves as the academic elite of this evidently venerable institution.

For two hours we shall watch them, in an environment oddly untroubled by any member of staff. Sometimes they work; usually they are about the business of tormenting each other (intentionally or not) or being tormented.

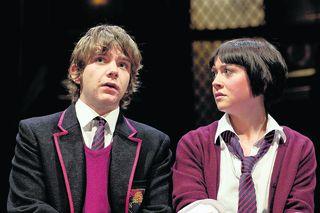

An unintentional tormenter is new girl Lily Cahill (Laura Pyper), a pert lass of Irish background, who has at once caught the eye of William Carlisle (Rupert Simonian), a garrulous fabulist whose fertile, scattergun imagination charms us from the start. She, though, prefers the looks and well-developed muscles of gym-honed Nicholas Chatman (Nicholas Banks) with whom she is soon conducting a clandestine affair.

By contrast, the odious Bennett Francis (Edward Franklin) has a deliberate mission to bully. He is socially a cut above the others, one suspects, an impression reinforced by the sophistication of girlfriend Cissy Franks (Ruth Mills) whose terror of disappointing her pushy parents through exam failure eloquently shows the pressures under which some youngsters’ school work is conducted in these ultra-competitive times.

In his superior, hectoring demeanour Bennett is reminiscent of the Rik Mayall character in The Young Ones. His principal victim is mathematics nerd Chadwick Meade (Mike Noble) — to whom, when he eventually fights back, is given by writer Simon Stephens the great speech of the play, an apocalyptic vision of disaster for the world. But he is not above putting the boot into the maternal Tanya Gleason (Katie West), chiefly taunting her for being fat.

These scenes are painful to witness, leading one to wonder why they are tolerated by the others. In particular, it seems strange that Nicholas, clearly a good egg, does not intervene. But then, in a clever plot development, it becomes clear that he and Bennett are on close terms, perhaps even — though unrecognised by either — romantically drawn towards each other.

The result of all this is compelling viewing, with an edgy, slightly unreal feeling that is heightened by sudden explosions of very loud rock music. The shocking act of violence at the play’s climax supplies a coup de théâtre I have rarely seen matched.

This brilliant and unsettling production, under director Sarah Frankcom, can be seen until Saturday (box office tel. 01865 305305 — www.oxfordplayhouse.com).

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article