Comradeship, brotherhood, mateship — call it what you will, male friendship has been around far longer than Hollywood and its newly-discovered ‘bromance’ would have us believe. Ever since Macbeth fought alongside Banquo or Gerald and Rupert wrestled by D. H. Lawrence’s firelight, the bond between men has been celebrated in literature. Not so in opera.

A genre of the explicit, with one eye always on musical textures, opera has tended to privilege the primary-coloured intensity of male-female romance — with the soprano-tenor love duet at its core — over the unspoken everyday affection between men. Bizet’s The Pearl Fishers is that bravest and most unusual of things: an operatic paean to male friendship. In Penny Woolcock’s new production for English National Opera it’s also as close to a success as this deeply flawed work is likely to come.

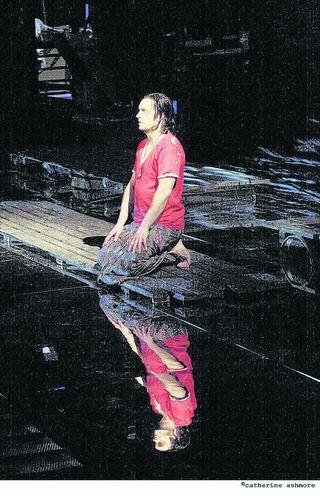

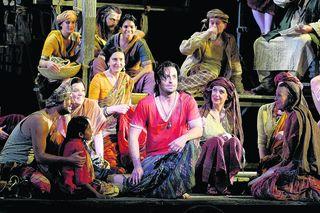

Dick Bird’s set thrusts us from the original Ceylon into the noise and cheap colour of a contemporary Sri Lankan shanty town. Perched precariously on raft foundations, the town toils upward, clinging cockroach-like to the steep cliffs. The sea itself is everywhere, a living force, representing by turns a home, a livelihood and a rising threat to the fragile lives of its inhabitants.

A critic of Bizet’s day famously quipped of The Pearl Fishers that, “there were neither fishermen in the libretto nor pearls in the music”, an accusation more felicitous than it is true. The score, all sinuous oboes and zesty brass, yields genuine melodic rivals to the famous duet Au fond du temple saint, as well as some of Bizet’s finest chorus writing.

In the pit young Scottish conductor Rory Macdonald drove proceedings energetically forward, drawing some unusual passion from the orchestra, but onstage successes were mixed. The light tenor of (Woodstock resident) Alfie Boe is daily growing to match his assured stage presence, and proved itself the equal of Freddie Tong’s’s warmly Lemalu-esque baritone. Hanan Alattar as Leila however was a little stiff (not aided by Martin Fitpatrick’s leaden and lumpish translation, bogged down in its pettifogging English consonants) and perhaps overfaced by the self-conscious virtuosity of the part.

With a climax as nonsensical musically as dramatically, The Pearl Fishers’ tragic flaw is all too evident. The opera is heady, uneven and illogical, yet rather than conceal or distract, Woolcock chooses instead to expose its fault-lines, mirroring the work’s flaws in her generous production. Both the iconoclastic bravery of its male-dominated subject and the naïve Orientalism of its treatment are offered up to the audience — not polished but honest and strangely potent. ENO’s new Pearl Fishers is a failure, but as intelligent and exciting a one as the opera itself.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article