That fine historian David Kynaston celebrated — if celebration there was — his 62nd birthday eight days ago, two weeks ahead of my reaching this same gloomy anniversary. Our being of an age means that we share many memories and can call up similar cultural references. Since these supply a lot of material for David’s books, it is not surprising that I enjoy them so much. We wallow together in the same warm bath of nostalgia (if the indecorous vision inspired by this metaphor is not judged too repellent).

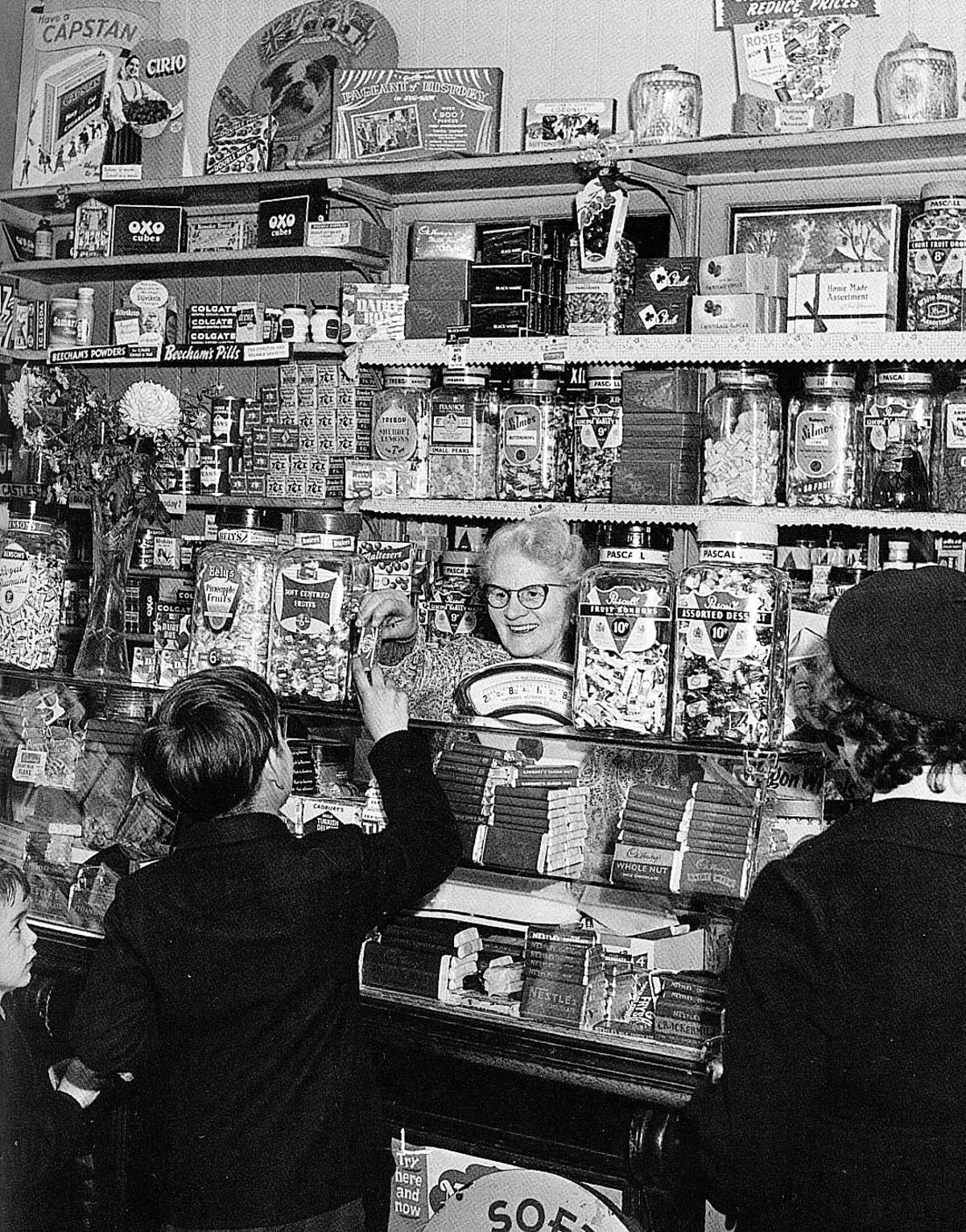

His Tales of a New Jerusalem is a projected sequence of books about Britain between 1945 and 1979. The latest volume, Modernity Britain (Bloomsbury, £25), advances the story to the years 1957-59, taking us well into a period which, in my case at least, is vividly recalled. The date of 1957 is the first I remember writing — with primitive wooden pen, its brass nib dipped into inkwell — at the head of a piece of work in the manner demanded at my infants’ school. In those days no compulsion was greater than to spend such limited funds as I could wheedle from my parents in a sweeetshop like the one in the splendid photograph on the right. Its caption in the book (“Unrationed sweets: London, 1957”) rather misleadingly suggests confectionery had just come off ration; it was available without limit, in fact, from 1953.

Close study of the photograph reveals that the smiling proprietor, who is seen handing a two-finger Kit-Kat to an eager lad, stocked products that would have been considered rather unusual in a sweet shop at the time. I can make out, for instance, pots of hair cream, tubes of Colgate toothpaste, sachets of Silvikrin shampoo and tins of Oxo cubes. There is a Pageant of History jigsaw, too.

Though no cigarettes are on view, an advertisement for Capstan suggests they were probably sold. Under the counter? Hardly, although by this time cigarettes were starting to get a name as something not entirely good for you. There were even suggestions of legal curbs, which, said a newspaper, would “run counter to British sensibilities”. The editorial added that since there was “no evidence that smokers harm anybody but themselves . . . an act forbidding smoking in public places would have no more moral validity than one prohibiting it altogether”.

Remarkably, this was the Manchester Guardian, which in those days advanced rather different ideas about freedom than the hectoring, lecturing Grauniad we all know and loathe today.

Fry’s Turkish Delight also features in the sweet shop picture, stacked beside the Cadbury’s variety it was soon to drive out of the market (I have no memory of it, at any rate). Fry’s version with its unforgettable TV advertisement (“Full of Eastern promise”) was among a number of products new on the market then. Others included the scientifically designed (by Lyons) instant porridge known as Ready Brek, ‘the new exciting taste of Gibbs SR’ (toothpaste), the original aftershave (Old Spice), the Hoovermatic twin tub.

Nothing, I think, quite revives the flavour of an age like a list of some of its commercial products. Kynaston supplies an admirable one towards the end of the book, which includes Picnic, Caramac, Bettaloaf, Nimble, Sifta Table Salt, Player’s Bachelor Tipped (possibly the first gasper I tried), Twink, Pakamak, Odo-ro-no, new Tide “with double-action Bluinite”. The list begins with Galaxy, a chocolate not actually sold in the UK until 1960. Anyone recall its TV advert? “The lights are going out all over Britain. Everyone is doing the Galaxy dark room test.” What was that? An attempt to see if the chocolate could be distinguished from the (unnamed) brand leader, Cadbury’s. The answer? I think you can guess.

Oxford figures prominently in the pages of Modernity Britain, with, for instance, the fall at long last of the notorious Cutteslowe Walls, and the arrival in 1958 of the first families in Blackbird Leys (“acres of unlit building sites, inadequate police supervision, parental apathy”, said “a local paper”, though not us, the book’s notes would suggest).

Good use is made again of the diary of clergyman’s wife Madge Martin, in the Oxfordshire History Centre. Much of it is concerned with entertainment. In London for Anna Neagle in No Time For Tears, she finds Piccadilly Circus and its environs “filled with the lowest type — Teddy boys with their friends of both sexes, etc”.

Visiting town in May 1957 she was driven by “horrid” weather to the Cameo Royal and a “naughty French film” with “the kitten-like Brigitte Bardot”. Madge’s hubby went along too, but I feel sure this was only because of the film’s title: And God Created Woman.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article