That artistic life must proceed through adversity was clearly a principle dear to the heart of Oscar Wilde, whose greatest work, The Importance of Being Earnest, was written as the shadow of shame and imprisonment loomed over him. Rupert Everett, whose star turn as Wilde I review today in Weekend, might find himself reflecting on this theme very soon.

Julian Mitchell’s public school drama Another Country, in which Everett made his mark on the West End stage in 1982, is being revived by Oxford students this week at the Playhouse. Everett has expressed a wish to see it, possibly at a matinée if his schedule for The Judas Kiss permits. When he does, he will find in ‘his’ star role of Guy Bennett — a gay spy-to-be, clearly based on Guy Burgess — a young man touched by family troubles scarcely less shattering, and nearly as well publicised, as those of Wilde.

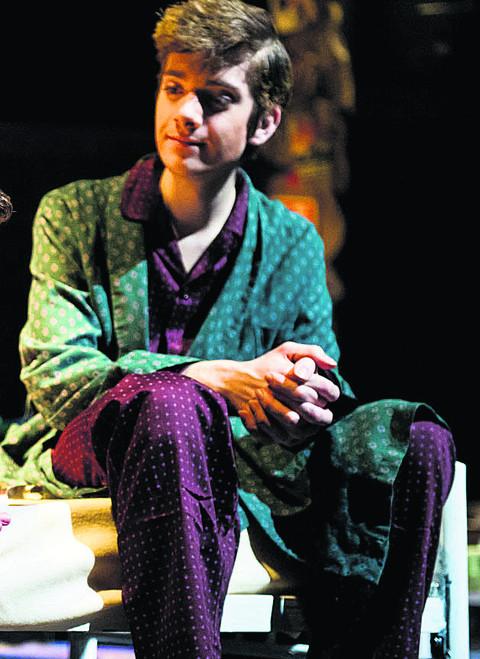

He is Peter Huhne, estranged son of former cabinet minister Chris Huhne, who as I write awaits sentence following his guilty plea to an offence of perverting the course of justice. The St Peter’s College student’s messages to his father, widely aired at the start of his mother’s trial on the same charge, achieved a degree of viciousness that came close to matching the outbursts, in speech and letters, of Wilde’s young nemesis, Lord Alfred Douglas. Everett might find himself pondering on this too.

Some readers will consider it in bad taste that I should be mentioning all this today. Perhaps it is. But I had intended to write of Another Country long before I knew of Peter’s involvement in the production. To have overlooked his presence in the cast would have been an absurdity, and besides — as my first sentences indicate — I feel I must applaud this firm adherence to the rule that ‘the show must go on’.

By the time this appears, I shall have seen the play, and hopefully enjoyed Huhne’s work in it. This seems likely, as he gave a fine performance as Italian immigrant Rodolpho last autumn in a Playhouse production of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge.

It might seem inappropriate to link the fate of Chris Huhne to that of Oscar Wilde. Except, of course, that the downfall of both men was precipitated by the persistence in a lie. In Huhne’s case it was that the missus had been driving the car; in Wilde’s that he was not the “somdomite” that Lord Queensberry claimed him to be.

In this connection might I be permitted to pick the brains of my well-informed readers? His Lordship’s fatal calling card, left for Wilde at the Albemarle Club, is reproduced in the programme for The Judas Kiss. It shows that he favoured the style ‘Marquis of Queensberry’. Why, then, is he always referred to in print as ‘the Marquess of Queensberry’?

The Judas Kiss is by David Hare and dates from 1998. Four years before, Hare had supplied a translation of Bertolt Brecht’s The Life of Galileo for the Almeida Theatre Company. This may explain the coincidence of there being two characters called Galileo mentioned in adjacent notices on our theatre page today.

The Judas Kiss’s Galileo is an Italian fisherman, daringly played as nature made him by Tom Colley. The result — perhaps intended — imitates the swarthy local boys captured naked in Sicily by the photographer Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden, whose pictures enjoyed surprising popularity in Victorian drawing rooms. Wilde visited the Baron in Taormina, the Sicilian town which he helped to make fashionable. Sadly, details of their conversation are not known.

Internet chatter has commented on Tom Colley’s ‘bravery’ in strutting his stuff. But isn’t this what actors do? What interests me is whether he is encouraging friends and family — his grandmother, say — to watch his performance.

“Do come and see me” has an entirely different meaning in this context.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article