‘It is unusual for [Anthony Trollope] to use a real place name for the action of his fiction, as he does in Old Man’s Love,” writes John Sutherland in one of his explanatory notes supplied in the Oxford University Press’s World Classics edition of the novel. While I must accept the opinion of the learned professor, the author of Victorian Novelists and Publishers, I should point out that while Trollope’s use of a real name here might be unusual, it is far from unique in his oeuvre.

As it happens, two other novels by the author I read during a recent holiday are also exact in their depiction of place. An Eye for an Eye — a surprisingly frank account of pre-marital sexual malarkey, which is again edited for World Classics by Prof Sutherland — is set in a lovingly described Co. Clare, with the soaring cliffs of Moher (600ft high) playing a central part in the drama. The Struggles of Brown, Jones and Robinson, an undeservedly little-known comedy of business life, focuses on commercial London, many of whose thoroughfares — including Little Britain, Snow Hill and Cowcross Street — and the markets of Smithfield and Billingsgate are clearly identified.

As an aside, I might note the curious circumstance that all three of these Trollope paperbacks, which I bought from an Oxfam bookshop in Stratford-upon-Avon, turned out to have once belonged, as a signature on the title pages makes clear, to someone I know. Next time I see him I shall mention my surprise at his decision — unusual in a Trollopian — to part with such precious volumes. (A rich man, he has possibly now acquired a uniform edition in hardback.) A book I have no intention of parting with — indeed, I am already halfway through my first reread — is Elanor Dymott’s Every Contact Leaves a Trace (Jonathan Cape, £12.99).

This is a remarkable debut novel by a woman — so her brief biography on the jacket reveals — clearly remarkable in herself: “Elanor Dymott was born in Chingola, Zambia, in 1973. She was educated in the USA and England and also spent parts of her childhood in South East Asia. Having read English at Oxford he qualified as a lawyer before becoming a law reporter.”

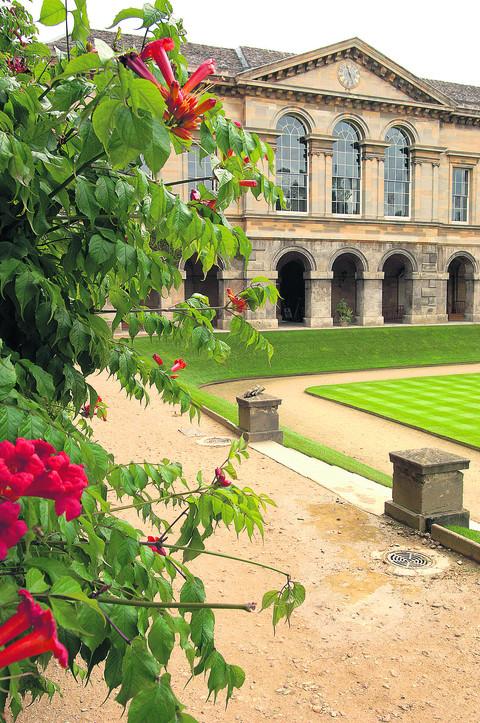

It will come as no surprise to anyone who as much as glances at the novel to learn that the Oxford college at which she read English was Worcester. Most of the events depicted take place in and around the college’s ancient buildings. The event that sets going the plot is a murder beside its famous lake.

This might suggest we are in for further Oxford detective fiction in the manner of Colin Dexter with Inspector Morse. Not quite. Though there is a whodunnit element concerning the killing of the vivacious Rachel, the focus of the book is more on psychology, especially that of her husband, the lawyer Alex, who is initially suspected of involvement in her death.

The novel goes on to consider their time together — though not in that sense — at the college and the remarkable menage of which she was part.

As one who knows Worcester reasonably well, I was delighted to find its gardens and buildings so well described. Some of its people, too. The recently retired English tutor Edward Wilson, whom I have met on a number of occasions, is there in aspects of Rachel’s tutor, Harry Gardner.

Ms Dymott acknowledges this at the end of the book, writing: “Those that know Edward, or know of him, will perhaps recognise him as a source from which I drew in creating Harry Gardner. I would like to note that, to the extent that Harry is a character drawn from life, all of the good in him comes from Edward [and from three other named dons].”

Something of the flavour of Ms Dymott’s writing can be seen in the foregoing. At once precise and, paradoxically, rambling, her dense thickets of prose must be tackled with vigour by those searching for her meaning. The effort is worth it, though.

The new Provost of Worcester, Jonathan Bate, a considerable English stylist himself, is an admirer of the novel, as he told me at a recent dinner in Magdalen College. He is too lately come to Worcester to figure in it.

As for Edward Wilson, I have so far not canvassed his opinion. Meticulous in his own writing, however, he might consider that Harry’s syntactically flawed letter on Page 80 would not be recognised as one that might have come from his pen (fountain, naturally).

Mr Wilson might also feel inclined to point out that ‘underway’ (oft appearing thus) is actually two words and that ‘alright’ (another regular from Ms Dymott tolerated by her editors) is not all right.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here