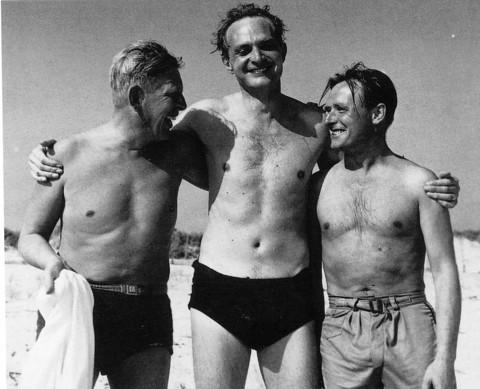

Since it’s summer (of a sort), let us begin on the beach, or rather with a reference to it. W.H. Auden is driving from London to Oxford, for his installation as the university’s Professor of Poetry, in June 1956. His slightly nervous passenger Stephen Spender, who recorded their conversation in his Journals, is wondering whether their pal Christopher Isherwood “had any sense of having failed in his vocation as a writer”. Auden replies: “Perhaps the truth of the matter is that what Christopher likes is lying in the sun in California and being surrounded by boys who are also lying in the sun”.

Famously disciplined where his own work was concerned, Auden could make such a remark with no fear of provoking comments about pots and kettles. His achievement is a mighty one, as great as that of any 20th-century poet. But Spender? His was a life of artistic disappointment. More intent on playing the part of a literary man — at conferences, on the lecture circuit and as a reviewer and editor — he had little time left actually to be the thing.

He was the first to acknowledge the comparative paucity of his creative output. It is a recurring theme of his Journals, almost one million words of which were written from 1939. A few months away from his death, for instance, in February 1995, he responds to critic Philip Hensher’s opinion that he had “always been elevated by the company he keeps”. He admits the justice of this — his inferiority to his friends in terms of output — and adds: “I want a few of my poems to survive and perhaps some memory of myself also, as distinct from any group.”

Assisting in this process of survival, for sure, will be the Journals themselves. A new selection from them has just been published (Faber and Faber, £45), under the editorship of Laura Feigel and his authorised biographer Prof John Sutherland, with input from his wife, the former concert pianist Natasha Litvin.

One suspects that this ‘input’ was rather more to do initially with what should be left out, principally where this concerned her husband’s ongoing sexual involvement with men. Her own death in 2010 removed this constraint, enabling us to find out, for instance, about his affair with a American nearly 50 years his junior, who sadly died of Aids. Natasha had been aware of this at the time, as a consequence of an overheard telephone conversation. But both stuck firm to an agreed line, that his gayness had been a passing phase and over years before.

Though I mean it as no criticism, the Spenders’ attitude contrasts sharply with that of Christopher Isherwood, whose own final volume of diaries has also just been published. The title Liberation (Chatto & Windus, £30) refers to the campaign for acceptance of same-sex affairs in which he played a prominent role.

Though one hardly thinks of the Daily Telegraph as a flag-flyer in this area, it was actually an article about Isherwood in this newspaper, by Brendan Lehane, that ‘outed’ him in 1970. He was pleased about it, too. “The article says I am homosexual, quite flatly, without further explanation,” he wrote. “I think this is the first time anyone has said this right out, in print. I am glad [Lehane] did.”

That Isherwood did considerably more than loll on beaches is evident throughout this consistently entertaining book. His was a life led among a gallery of celebrities, a number of whom (including David Hockney, Igor Stravinsky and Gore Vidal) also crop up in Spender’s Journals. While the writer’s preoccupation with his and others’ illnesses, real or imagined, sometimes palls (‘Health’ is one of the longest entries under Isherwood’s name in the index), one can forgive this as an understandable concern of old age.

At a time when some of us are also thinking about beaches and our reading matter there, Isherwood and Spender are both worth taking along — in ebook format if their hefty weight is off-putting.

But don’t read Spender anywhere where laughter might be misconstrued. Who could keep a straight face on learning, for instance, why he considered it “an honour” to be called “a prodigious bore” by Virginia Woolf?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article