Sophie Treadwell’s influential 1928 play Machinal begins amid the clattering of typewriters and incessant ringing of telephones — a racket that supplied the background to daily labour for all of us who knew office life before computers and email. Conversation of these American wage slaves rises above it: inane (“Hot dog!”), cliché-ridden, poetically repetitive in the telegraphese manner favoured in expressionist drama.

From the cacophony themes emerge — that one of their number is late, again; that this might spell trouble for her; that, in fact, it probably won’t, since following the arrival of the latecomer (Nouran Koriem) comes new evidence that she’s fancied by the boss (Tim Kiely).

Should she take him? This becomes the principal concern in the second of the nine sections of this compelling play in which its unnamed (at this stage) protagonist is urged by her hard-up, partnerless, nagging mum (Caitlin McMillan) to grab at a union useful to all.

A loveless marriage to a dull-dog, money-fixated bore? Yawning years ahead as a stenographer? The dilemma is explored in the first of the play’s long, self-revealing speeches — another trademark of expressionism. Strange as these probably sounded to the audiences who first heard them — a reason perhaps for the play’s comparatively short Broadway run — they now come over as being oddly prescient of the era of television drama.

Marriage proceeds, soon followed by childbirth, an event which fuels the woman’s developing neurosis. A hospital scene shows her victim of a heartless medical establishment — bloody, supine, speechless.

Then we are in a speakeasy, where booze circulates as three sexual unions are fixed. At one table Liam Steward-George shows us (most entertainingly) an aesthetic predatory gay hitting on a callow youth with the help of a bottle of amontillado: “Let’s go back to my room. I have a first edition of Verlaine that will make your mouth water . . .” The lad follows obediently.

Our sad mother easily succumbs, too, to the temptation offered by an easy-going young man (Jo Allan)— clearly a practised seducer — whom she encounters there. In his bed she finds happiness of a sort she has not previously experienced.

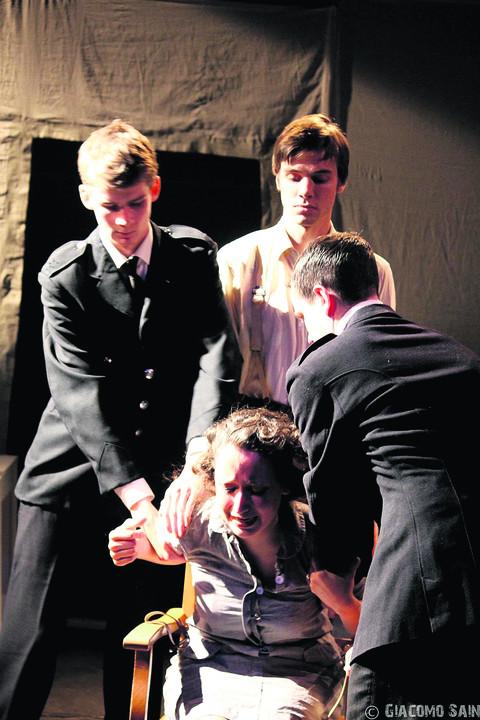

The affair propels the story towards a shattering climax in which figure the woman’s trial for murder — only now do we find she is Helen — and her execution in the electric chair. In both, once more, a grim and unfeeling establishment is shown about its work.

Watching the play on Thursday in a setting not unfamiliar to judicial execution — the former Oxford prison, where it can be seen till Monday — I was moved and impressed by the powerful statement it made on behalf of women in a male-run society.

While one should never, of course, condone murder, that someone could have been driven towards it through the pressures of work, and an unwise route to escape it, can only be a source of pity.

This well-acted, good-looking production (director Jack Sain) offers an eloquent evocation of its period through costumes — some removed daringly close to the audience — and music, including Bessie Smith’s incomparably lovely (and true) Nobody Knows You When Your’re Down and Out. It is a top-quality piece of work that can only boost the reputation of Oxford student drama at the Edinburgh Fringe where it is being performed (C Nova) by the Oxford University Dramatic Society from August 3 to 26.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article