Compton Verney, in Warwickshire, has opened its doors to the 2012 season with exhibitions on Impressionism and Gainsborough landscapes, both of which run until June 10. The larger of the two, Into the Light: French and British painting from Impressionism to the early 1920s, brings together a range of artists from both sides of the channel — including Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, Walter Sickert and Vanessa Bell — to present a picture of the important transitions in subject matter and painting technique that occurred during this 50-year period.

Rather than simply showing another exhibition of Impressionist paintings, uplifting as that may be, Compton Verney’s exhibition of 54 rural and coastal scenes, and accompanying catalogue, looks beyond the superficial and asks questions.

Curator Sam Smiles, Professor of Art History, the University of Plymouth, challenges the idea that a huge chasm existed between French and British artists at that time. The commonly held view was that British artists were merely following in the wake of French developments and seldom developing them, but Smiles asks whether they were using what they learnt in France or from French art to develop a style more suited to British interests, and suggests “a real dialogue” was going on.

The first gallery offers a ‘prelude’ with some of the ‘stars’ of French Impressionism, Monet, Pissarro, Sisley and such like, and some who exhibited with them, Boudin, Cézanne, Gauguin, for instance. Also, younger British artists like Philip Wilson Steer who looked to France for inspiration.

Among major trends in painting practice at the time were explorations of light, including a commitment to painting en plein air (in the open air) directly from the subject. There was also a move towards naturalism, depicting real people in real surroundings rather than using models.

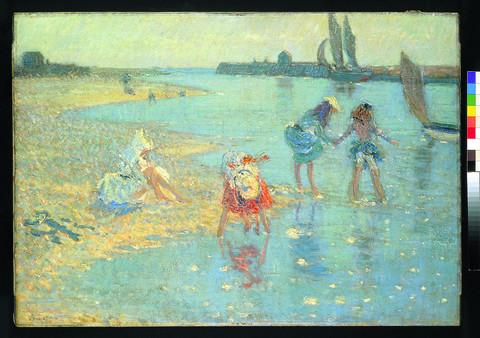

Steer, for example, in Walberswick, Children Paddling (1891, see above) used bright unmixed colours to achieve flickering light effects. In Winter Work (1883) George Clausen, painting directly from nature, depicts the hard work of field labourers preparing beets. By comparison, 20 years later, in A Frosty March Morning (1904), influenced by Impressionist landscape, Clausen concentrates on atmosphere and light effects.

Stanhope Alexander Forbes’s A Fish Sale on a Cornish Beach, 1884, encompasses all the above. It’s a tour de force, the girls, the fish, the boats, the sky gleaming in the early morning light. But don’t miss the two lovely little studies either side of it.

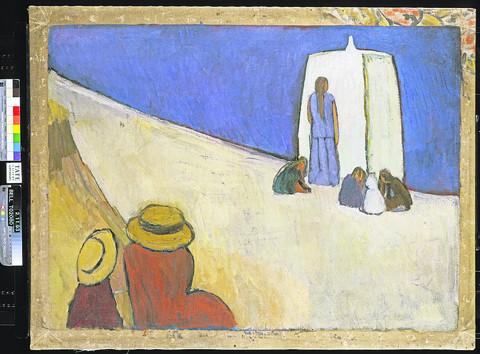

The exhibition ends brilliantly with paintings influenced by later developments in European art, conspicuously by the Manet and the Post-Impressionists London exhibition of 1910, Fauvism and Cubism. Several works here teeter on the edge of abstraction. There’s Spencer Frederick Gore’s The Beanfield, Letchworth, all zigzag patterns and non-naturalistic colour; geometry in Robert Polhill Bevan’s Devon paintings pointing to Cubism; and Vanessa Bell’s Studland Beach strikingly Fauvist colour and simplified forms.

Next time I will look at Gainsborough’s Landscapes. For information: www.comptonverney.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article