The words they produced were few. But 100 years after the sinking of the Titanic, the distress calls sent by the doomed liner’s two radio operators must be counted among the most poignant treasures of Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

Even now it is impossible to read the desperate calls for assistance without imagining the terrible conditions 22-year-old junior wireless operator Harold Bride and his senior, Jack Phillips, 25, were working under.

At about midnight on April 14, 1912, Phillips was ready to go to bed when the Titanic’s captain Edward Smith entered the Marconi cabin and instructed the wireless operators to call for help.

Over the last two hours of the Titanic’s life they sent distress calls continuously to all ships within range of the powerful wireless transmitter.

Agonisingly, one ship, the Californian, was actually within sight, with its officers even able to see flares sent up from the sinking Titanic.

The agony would have been all the greater if the Titanic operators had known that the Californian’s only wireless operator was sleeping, left undisturbed until several hours after the Titanic had been swallowed into the cold Atlantic.

Phillips and Bride both refused to leave their posts even when released from their duties by the captain. They were to be among the last to leave the stricken ship. By the time they left the wireless room, water was already washing over the decks.

Remarkably, both men were washed from the deck into an upturned lifeboat. Phillips perished but Harold Bride was to survive.

By the time he was carried on to the Carpathia, the ship which picked up the Titanic’s survivors, he had lost the use of both legs from exposure. Nevertheless, he quickly headed for the wireless room to assist the Carpathia’s only operator send messages to relatives of Titanic passengers.

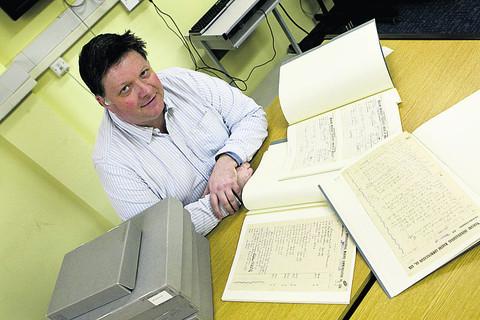

The story is recounted to me by Michael Hughes, senior archivist at the Bodleian.

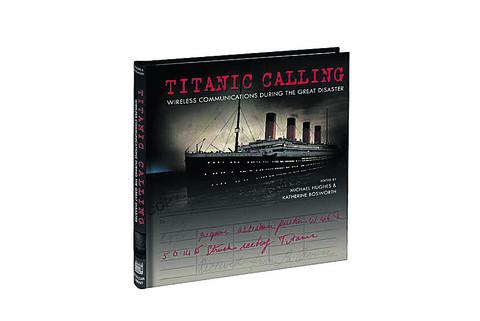

Together with fellow archivist Katherine Bosworth he has written a book, to be published on the anniversary of the tragedy, focusing on the role of wireless in this greatest of all maritime disasters.

Titanic Calling (Bodleian Library £14.99) draws heavily on the Bodleian’s unique Titanic Collection, which arrived in Oxford in 2004 as part of the Marconi Collection that was given to Oxford University.

He will be giving a lecture at the Bodleian on April 26 (free admission) while a Titanic display will open at the Bodleian between April 14 and May 13, showing examples of Oxford’s Titanic archive.

It contains some 3,000 messages related to the story of the Titanic, bringing to life the voices of the individuals at the centre of the drama through radio operators’ logs and messages between the Titanic, other ships and shore wireless stations.

Some offer insights into the preoccupations of passengers, unaware of what was about to befall them, like the message to the actress Dorothy Gibson from her lover. (She would survive to appear in the first Titanic movie, the only one to star an actual survivor.) The archive contains the numerous warnings of ice, including some reporting large icebergs unusually far south and alarmingly close to the Titanic’s course. Then there are the distress signals sent to nearby ships and passed rapidly across the Atlantic, as the desperate attempt began to save hundreds of lives.

This section begins with Phillips sending the “CQD” Marconi distress signal: “CQD Position 41.46N 50.14W require assistance struck iceberg — RMS Titanic.”

And it ends with the Titanic’s final, broken message recorded by the distant SS Virginian: “Unable to make out his signal. Ended very abruptly as if power suddenly switched off.”

The vast bulk of the messages, says Mr Hughes, detail the story of the rescue of the survivors, with messages of survivors to family and friends.

Mr Hughes said: “The distress calls from the Titanic and messages from the survivors are deeply poignant, the more so as a result of their brevity. Chargeable by the word and needing to be sent rapidly by Morse code, their short and abbreviated style is surprisingly familiar to a modern audience, accustomed as we are to the staccato nature of Twitter.”

Some may be surprised to learn that nearly all passenger ships were fitted with wireless technology in 1912, with the wireless equipment of the Titanic the most advanced and powerful around, able to transmit up to 400 miles during the day and 2,000 miles at night.

“Normally messages and radio operators’ logs would not have been kept,” he explained. “We have all this documentary material relating to the sinking of the Titanic because it was gathered together for the British inquiry into the sinking.”

The archive contains the radio operators’ logs for all the ships in the vicinity of the Titanic, providing the most direct evidence of what took place. The only parallel is the evidence submitted by passengers and crew at the US and British inquiries into the sinking. Copies of these are to be found in the collection also.

But for all the vast amount of material, mysteries remain. For example, while Captain Smith undoubtedly saw about half a dozen ice warnings and acknowledged them, it is not known whether he saw one sent a few hours before the disaster from the westbound SS Mesaba, which read: “From Mesaba to Titanic and all eastbound ships. Ice report in latitude 420N to 41025’N, longitude 490W to 50030’W. Saw much heavy pack ice and great number large icebergs. Also field ice. Weather good, clear.”

While the operator of the Mesaba made a note appearing to show the Titanic operators’ reply, there is no decisive evidence to show Jack Phillips received it, or if it was passed to Captain Smith.

Were there failures?

Mr Hughes replies: “We can’t be sure. But I would say there was certainly some breakdown in communication.”

The final significant message came from the Californian, believed to have been within 20 miles, to say it had stopped for the night and was surrounded by ice.

The Californian’s operator told the US inquiry he received the response from the Titanic: “Shut up, shut up, I am busy; I am working Cape Race.”

For all his bravery after the collision, this has led to speculation that the heroic Phillips may have neglected such important messages to prioritise money-making commercial messages in those crucial hours before the iceberg was struck.

We are unlikely to ever know.

But of one thing Mr Hughes is certain. Wireless was at the heart of the story and it took a disaster on the scale of the Titanic to bring about a proper examination into the unused potential of wireless communication in improving sea safety.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here