Extracting the Mona Lisa from the Louvre proved too much of ‘an ask’ for the organisers of the National Gallery’s blockbuster Leonardo da Vinci exhibition. But La Gioconda is proving to have a rival in The Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (‘The Lady With An Ermine’ — above). Some critics are arguing that this is an even finer work of art. Not only are we offered another beautiful woman with an enigmatic smile but one who is accompanied by a superbly executed animal. I was captivated by the creature. As Kenneth Clark noted: “The modelling of its head is a miracle; we can feel the structure of the skull, the quality of skin, the lie of the fur. No one but Leonardo could have conveyed its stoatish character, sleek, predatory, alert, yet with a hint of heraldic dignity.”

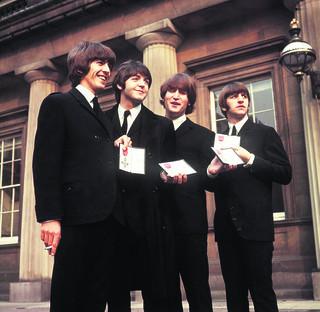

The notion of the Mona Lisa being eclipsed by a lesser-known rival was in my mind on Sunday night as I watched the second part of director Martin Scorsese’s screen biography of George Harrison on BBC2. Here was a musician generally considered the inferior as a songwriter of his fellow Beatles Paul McCartney and John Lennon but who was arguably an even greater talent.

Never allowed as wide an exposure of his work as his rivals on The Beatles’ records, he had so much material stocked up at the time of the band’s break-cup that his solo offering, All Things Must Pass, filled three discs. It is considered — as George Harrison: Living in the Material World made clear — the pinnacle of any of the Fab Four’s post-Beatle achievements.

His later co-operation in The Travelling Wilburys with the likes of Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and the great Roy Orbison also marked him out as a musician of a very special sort.

The thesis, I have to say, is one that appeals to me since I have always regarded Harrison, who lived at Henley, as our ‘local Beatle’. He was even known to jam occasionally — once to the anger of neighbours who complained of noise — at the Crooked Billet pub in Stoke Row (where Kate Winslet celebrated her first marriage). One of his mates there, Joe Brown, put in a fleeting appearance in the film, in the form of a still photograph. So did another pal, ‘Legs’ Larry Smith, of the Bonzo Dog Doo- Dah Band, who would have had much of interest to say had be been interviewed. Harrison is also the only Beatle I have met. This was as long ago as the summer of 1978 after a Boomtown Rats concert at the New Theatre. Bob Geldof had invited me for a drink backstage where I was surprised to find Harrison one of the party. Geldof was on such friendly footing with him that I concluded they must be old mates.

It was only years later, when Geldof published his autobiography, that I learned that this was actually their first meeting and that he was (presumably) as much in awe of the Beatle as I was.

Harrison’s relaxed manner, in fact, put everybody at their ease. He was clearly as nice a man as his ‘love and peace’ image suggested. This made the more shocking the vicious knife attack on him at home in late 1999 by 36-year-old Michael Abram, later judged not guilty of attempted murder on the grounds of insanity.

George’s survival owed much to the intervention of his wife, Olivia, who fought off the intruder with a poker and a lamp. Hers was, without doubt, the most affecting contribution to Scorsese’s film, which will serve as a fitting memorial to a musician — and man — of a very special sort.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here