William Rees-Mogg thinks The Oxford Times is “a very distinguished regional paper” and said so when, in November 1979, we published a special supplement marking The Times’s return to the newsstands, under his editorship, after nearly a year away.

Having shown such warm regard for us in the past, Lord Rees-Mogg is not going to be given reason to revise his opinion, I hope, by anything I shall write today about his newly published Memoirs (HarperPress, £30).

But — and you must have seen this coming — there are features of the book that do invite criticism. Sometimes its pages provide an unintended source of amusement, often arising from the author’s assessment of his own worth. “I am not particularly modest,” he admits on page 262, by which time the reader has good reason to accept the veracity of this statement.

His style, too, can sometimes be a little comical. Admirers of Mary Dunne’s humorous classic, the spoof memoirs Lady Addle Remembers, may sense a familiar tone in Rees-Mogg’s entry about his mother: “She had a perfect voice, a sense of timing and a sense of occasion. She had the temperament of a star, but not of a star who made excessive claims for herself. She had wit and intelligence and energy and I remember her saying that she couldn’t understand people being bored because she’d never been bored in her life.”

Such passages as this make one utterly confident that it will not be long before the book gets the treatment from the nation’s greatest parodist, Craig Brown.

Occasionally, one feels, his lordship outdoes even Brown’s invention: “Many children start to ask metaphysical questions at an early age. My eldest daughter, Emma, entertained the Platonic idea of the pre-existence of souls at the age of four.”

From that astonishing observation to matters more mundane, Rees-Mogg does share with Sybil Fawlty a predilection for stating (as Basil put it) “the bleeding obvious”. Instance: Alec Douglas-Home’s accession to the Tory leadership was “a stitch-up”; Edward Heath was “not good with people”.

An appealing feature of the book — and indeed of its author — is that while Rees-Mogg’s finer points are paraded, so too are his failings.

In this connection it is commendable to see him recognising the accuracy, to some extent, of the portrait drawn of him by his Charterhouse contemporary Simon Raven in his Alms for Oblivion novel sequence. It is unfortunate, though, that he gets the name of the character wrong — “Somerset Lloyd Jones” instead of the correct Somerset Lloyd-James.

He acccepts that the portrait is “based on the less agreeable aspects of my schoolboy personality”. He does not say which aspects, but greed is probably among them, since this is what he admitted some years ago to Raven’s biographer, Michael Barber.

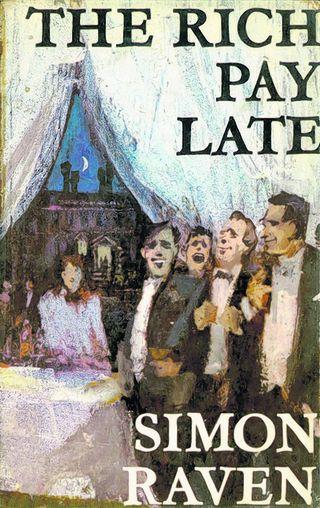

Lloyd-James — I was reminded from an enjoyable rereading of the first in the sequence, The Rich Pay Late (1964) — also has an appetite for shady business deals and flagellation. In these areas, I feel sure, Lord Rees-Mogg will in no degree have supplied inspiration.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here