With the image of Jack Black astride Blenheim Palace, in Gulliver’s Travels, still fresh in our minds, the historic house reopens on Saturday to tell an eccentric tale that has all the ingredients of a Hollywood movie — except this one is not fiction.

Until March 25 there will be an exhibition in the long library titled Gladys Deacon— An Eccentric Duchess. Gladys Deacon was indeed a duchess, the second wife of the Ninth Duke of Marlborough. The historian Hugo Vickers showed steely determination and great charm to get the reclusive duchess, in old age, to talk to him, even though she once said to him, with a twinkle in her eye: “Gladys Deacon? She never existed.”

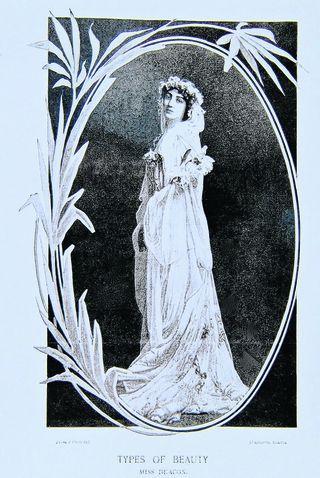

Hugo’s biography of her, Gladys Duchess of Marlborough, reveals several different personalities behind one face, except that changing face was as puzzling as her character.

She was born in Paris in 1881 and mostly grew up in France. Though an American, she preferred to consider herself French. Her early life is like something out of a Victorian melodrama. Her father, Edward Parker Deacon, beat her mother, Florence.

After inheriting a considerable fortune, Florence continued to enjoy a life for herself in Europe. Edward followed her to Cannes and shot dead the man he considered was his wife’s lover, in February 1892.

Considering the dramatic events of her childhood, it is perhaps not surprising that Gladys was considered to have acting ability.

In her youth, she counted Proust, Rodin and Monet among her friends. Indeed, Epstein sculpted a bust of her which is referred to as The Etruscan Bust. Gladys, who was famed for her beauty and attractive to men — including Bernard Berenson, Hermann von Keyserling, the Duke of Connaught and d’Annunzio — had a desire for a Grecian profile of perfection. To achieve that look she injected paraffin wax into the bridge of her nose, damaging her legendary looks.

Berenson wrote, “She looked like a porcelain doll, who had a swelling of the cheeks, and the red patch of which had all run into the face.” Despite the harm done to her appearance, the feature that dazzled was unaffected — her eyes. Standing in front of the main doors of Blenheim Palace, visitors can look up at the portico ceiling to three pairs of eyes — the striking blue eyes are those of Gladys Deacon!

They were painted, in 1928, seven years after her marriage to the duke, by the painter Colin Gill. She is said to have climbed the scaffolding to give the artist a blue silk scarf of the same shade as her eyes. You can also encounter her striking features in the lower water terraces where the heads of a pair of stone sphinxes are modelled on her.

She was a regular visitor to Blenheim and a friend of the duke’s first wife Consuelo Vanderbilt whom she replaced after the divorce. Her dream of marrying a duke, and Marlborough in particular, led to her undoing, as the marriage spiralled into disaster, until she was expelled from the palace in 1933. She became increasingly reclusive until her death in obscurity in 1977.

Lady Ottoline Morrell, the chatelaine of Garsington Manor, once described her as “the most intelligent woman in Oxfordshire”, and Gladys said of her situation: “I married a house not a man.”

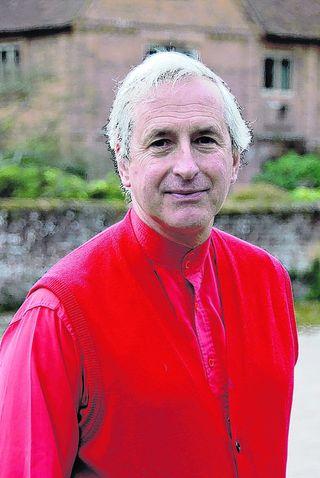

Hugo’s book is full of other equally disarming remarks. Her biographer (pictured right) has advised on this exhibition. He says: “When I first went to Blenheim as a teenager in 1968, the guides said, ‘We don’t talk about her.’ “So it is exciting to bring Gladys Deacon back to the palace after these long years. She was without doubt the most fascinating person I ever met. I am sure visitors will be amazed by her and by the range of her interests.”

Gladys is certainly an intriguing addition to a line of formidable duchesses. Sarah Churchill was obviously not a woman to be trifled with. John Singer Sargent’s evocative painting of Consuelo, whose fortune transformed Blenheim, radiates the strength of personality that led her to divorce the ninth duke.

Margaret Forster’s biography of Frances, the 7th duchess paints a very different picture of her from the apocryphal one. Now we have the opportunity for a rare glimpse into the life of a celebrated woman, once banished from Blenheim but now returned.

Among the exhibits are many photographs taken by Gladys during her years at Blenheim between 1921 and 1934. Some of these relate to the creation of the water terraces, but there are also portraits, house group photos, pictures of figures such as Winston Churchill, and many images and paintings to evoke a lost era.

Special costumes are being created to match images of Gladys from some of the photographs.

Blenheim Palace is repeating its popular annual pass ticket deal in 2011. When you buy a single day ticket to the palace, park and gardens you will be able to convert it into an annual pass, offering you unlimited entry for 12 months. Lunch on Sunday is served in the Orangery and will feature Valentine’s truffles and live music. To book call 01993 813874.

Gladys Deacon — An Eccentric Duchess ends on March 25. Details at www.blenheimpalace.com or call 01993 811091.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here