From the first few rooms it is clear that despite its title, Modern British Sculpture, the new exhibition Royal Academy of Arts (until April 7) is confined to neither modern nor British works and challenges in fact what is sculpture.

It starts with the Cenotaph, or a huge wooden replica of Edwin Lutyens’s monument, flanked by pictures of Jacob Epstein’s Cycle of Life series. The idea is to flag up the affinity between sculpture and architecture, to emphasise life-death opposition, and the abstraction-figuration choice faced by sculptors.

The next room, nicely designed, a colonnade of upright sculptures leading the eye down a long gallery with smaller pieces and reliefs lining the walls, contains a mix of ethnographic sculptures from the British Museum alongside early 20th-century figures by Eric Gill and others. The idea is to show the range of works that informed British sculptors early last century.

In the fourth gallery, the mighty figure of Queen Victoria looms over us in the form of an elaborate bronze public sculpture by Alfred Gilbert, from 1887. High on her plinth, she embodies the gallery’s theme of authority, the Establishment, the topic augmented by three other sculptures by former presidents of the Academy. She sits gazing disdainfully towards Phillip King’s blue-painted plastic Genghis Khan, and of course does not look at the two nude men in the room: Frederic Leighton’s athlete wrestling a python, and an awkward, troubled Adam by Charles Wheeler.

The show, controversial as much for its omissions as anything — no Anish Kapoor, Antony Gormley, Andy Goldsworthy, Rachel Whiteread and more — is not meant to be a survey of 20th-century ‘names’, curators say, but “a provocative set of juxtapositions that challenge the viewer to make new connections and break the mould of old conceptions.”

The trouble is that by including so many examples from other countries, other times, valuable space is lost for 20th-century British sculpture. That isn’t to say the ceramics (V&A loans) or antique or non-British works aren’t instructive or enjoyable to see. They are. They aid the sense of excitement in discovery the show wants to convey, and they make us think about British sculpture’s relationship with the wider world.

But I do wonder how well the juxtapositions or ‘sculptural dialogues’ — sculptures ‘speaking’ to one another — work when the rooms are crowded with people who can’t see all the works referred to at any one time. Or indeed make the intended connections between rooms, such as the colourful hanging planes of Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton’s Exhibit (1957; an early example of ‘installation art’) in a room leading on to Anthony Caro’s Early One Morning (pictured right). Exhibit is supposed to make a bridge between the Moore and Hepworth room (two crafted bronzes still retaining a sense of the carver) and Caro’s experiment in verticals and horizontals in painted steel and aluminium (the use of industrial materials rather than conventional).

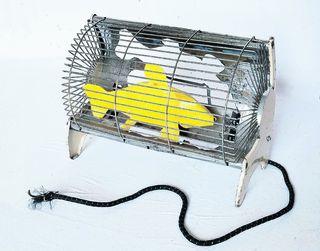

One unforgettable juxtaposition, however, is Damien Hirst’s fly-ridden barbecue scene placed in ‘filthy’ opposition to Jeff Koons’s ‘clean’ basketball in a tank. Etched on my mind for pleasanter reasons are Barbara Hepworth’s works, beautiful Pelagos for instance, Richard Long’s classic Chalk Line and Tony Cragg’s striking in texture and colour Stack. Epstein’s gigantic alabaster Adam as well — a relatively unknown sculpture introduced to me in this unusual show.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article