Well-known as it is, Sean O’Casey’s 1929 anti-war play The Silver Tassie is comparatively rarely seen. The Almeida’s 1995 revival under Lynne Parker and the RSC’s 1969 production — with the now-titled luminaries Ben Kingsley, Helen Mirren and Patrick Stewart all in the cast — are the only memorable ‘recent’ stagings in Britain. Modern audiences are more likely to know it from Mark-Anthony Turnage’s opera version for ENO a decade ago.

How welcome it is, then, that the renowned Irish company Druid should have brought their powerful and poetic production of the play to Oxford where — from the evidence of The Oxford Times’s library files — it has never been performed before.

This is a moving night of theatre, during which I found myself blinking through the tears more than once long before the end, a circumstance that has as much to do with the sinuous beauty of the writing as with the skills of the actors interpreting it. Music, too, plays an important part in the overall effect — appropriately jaunty at times — with Elliot Davis supplying fine new tunes to O’Casey’s lyrics.

The focus of the drama are representatives of the ‘doomed youth’ sent for slaughter and maiming in the trenches of the First World War. The ‘monstrous anger of the guns’, famously conjured in Wilfred Owen’s anthem to these men, is at once recalled here in designer Francis O’Connor’s giant tank in the French battlefield scenes of Act II, its huge barrel jutting out to the auditorium. Beneath cower the soldiers, among the symbols of a religion — the play has much to say on the subject — which their suffering cannot fail to call into question.

Here are some of the happy team of football players we earlier met on leave in Dublin. during which the jubilant Harry Heegan (excellent Aaron Monaghan), led them to victory, and the prize of a silver trophy, in an important match. From this ‘tassie’ the hero takes huge swigs of Sandeman's port in between his attentions to his beloved Jessie (Aoife Duffin).

Later the vessel will be seen again, in the affecting close of the play. Harry, now cruelly paralysed from the waist down, raises it to his lips as if it were a chalice, in a ceremony linked to his own misfortune, to that of his blinded army colleague Teddy (Liam Carney) and to the millions slaughtered on the fields of northern France.

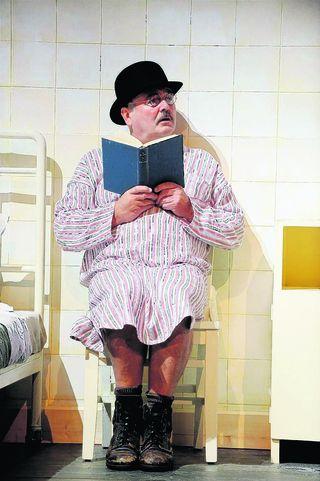

As I indicated, the play is not all gloom, with much of the welcome humour supplied by Harry’s dad Sylvester (Eamon Morrissey) and his pal Simon (John Olohan). Joshing about in their bowler hats, they look to be auditioning, two decades early, for roles in Waiting for Godot. Which is surely what director Garry Hynes intended.

There are also fine turns from Clare Dunne, as the religiously obsessed Susie, who goes on to become a martinet nurse in Harry’s hospital ward, and from Derbhle Crotty as Teddy’s wife, who is able to avenge herself quite terribly, once he is blinded, for the shocking cruelties he is seen to inflict on her at their Dublin tenement home in the days of his full health.

Until Saturday. 01865 305306 (wwwoxfordplayhouse.com).

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article