Alastair Lack reflects on the history of an iconic Oxford building — the Radcliffe Camera.

Every day, dozens of Oxonians and visitors must walk past one of the most significant paving stones in the city, without ever noticing it, let alone understanding its significance. A large, flat, unadorned stone, some 15 inches square, is set in the cobbles of the south-west corner of Radcliffe Square.

It marks the corner of the block of some 20 house properties bought by Dr John Radcliffe’s Trustees in the 1730s to form a site for the library that commemorates the great benefactor of Oxford University.

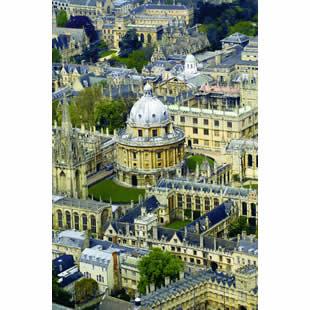

The Radcliffe Camera (called in earlier days the Radcliffe or ‘Physic’ Library) is the first circular and ‘science’ library in England and surely the finest 18th century building in Oxford. It stands at the very heart of the university in Radcliffe Square.

Nikolaus Pevsner, the eminent architectural historian, has written: ‘there is a density of monuments of architecture here which has not the like in Europe. The area by the Radcliffe Camera and the Bodleian is unique in the world’. Praise indeed, but he then adds: ‘it is certainly unparalleled at Cambridge.’ But who was John Radcliffe?

His life was a success story. Radcliffe rose from comparative obscurity to become the royal physician to William and Mary, and immensely rich in the process.

Born in 1652, and educated at Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School, Wakefield, he was barely in his teens when he entered University College and, at 18, became a fellow of Lincoln College. After taking a degree in medicine, he moved to London in 1684 and was soon earning 20 guineas a day.

By all accounts he was a straightforward and straight talking physician, who preferred fresh air to the then fashionable blood-letting. He treated his patients with candour, not least the King: ‘I would not have your majesty’s two legs for his three kingdoms’.

Just before his death, he became MP for Buckingham. Radcliffe took pride in writing little and reading less, remarking once of some vials of herbs and a skeleton in his study: ‘this is Radcliffe’s library’. The irony of his leaving money for a library was not lost on a contemporary, Sir Samuel Garth, who described it as: ‘like a eunuch founding a seraglio’.

When Radcliffe died in Radcliffe made his will in September 1714, money was directed for ‘the purchasing of the houses between St Maries and the scholes in Catestreet, where I intend the library to be built.’ The site was very cluttered. Earlier maps of Oxford show an area of houses fronting Catte Street, built right up to the Schools building, as well as gardens, Brasenose College outbuildings and Black Hall. The Radcliffe Trustees had long negotiations with the owners and tenants of the houses.

In 1720, an Act of Parliament was passed that enabled corporations within the university to sell ground for building the library, but the subsequent wrangles still took more than 20 years, with Brasenose finally getting an equal amount of land fronting The High in return for land they gave up.

The choice of an architect for the library was considered soon after Radcliffe’s death. There were eminent names in the frame — Wren, Hawksmoor, Vanbrugh, Thomas Archer, John James and James Gibbs. The early 18th century was a period of great architecture in Oxford and, of course, at Woodstock, where Vanbrugh was working on Blenheim Palace for John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough. In Oxford itself, Nicholas Hawksmoor designed the Clarendon buildings of 1711-15 and the North Quad of All Souls, with the famous ‘twin towers’. Elsewhere two academics, both amateur architects, added much to the Oxford landscape. Henry Aldrich, Dean of Christ Church, designed Peckwater Quad and All Saints Church in The High, which is now the library of Lincoln College). George Clark, fellow of All Souls, designed the new buildings of Worcester College and the Warden’s Lodgings of All Souls.

Nor should we forget William Townesend, a member of the famous family of Oxford stonemasons and builders.

Pevsner points out that he is called ‘architectus’ in accounts at Queen’s College and suggests he designed the New Buildings at Magdalen, while Howard Colvin detects his hand in the The Fellows’ Building at Corpus Christi and the Robinson Quad at Oriel.

Hawksmoor was brimming with ideas for Radcliffe’s ‘Physic’ Library, suggesting a rotunda, built on a square plinth — his model can still be seen in the Bodleian.

But in 1736, following Hawksmoor’s death, fees were paid to James Gibbs, the chosen architect. Gibbs was perhaps atypical for a British architect of the time. He was Roman Catholic, a Tory and had studied in Rome — which may explain the similarities between the Camera and a Roman mausoleum. He was certainly not part of the powerful and fashionable Palladian movement in England, but he was well known for buildings such as St Martin’s in the Fields in London, and the Senate House at Cambridge.

Gibbs was influenced not only by Rome but also by Christopher Wren, and was a master of what has been called a ‘distinguished but comfortable style’.

By contrast, the Radcliffe Library of Hawksmoor would have been more dramatic. Gibbs kept the rotunda design, but abandoned the plinth in the building we see today.

Work finally began in 1739 with completion in 1748. Built of mellow Headington and Burford stone, externally the building has three stages and internally two. Outside, the dome and cupola are covered in lead and housed in a ‘drum’ with windows. The upper floor has coupled Corinthian columns, with bays alternating between windows and niches. The ground floor is rusticated, with wide blocks of stone, and eight bays that were open until the 1860s, with an entrance up stairs on the north side.

Inside, the upper room is reached by a fine wrought iron staircase. Above the entrance is a portrait of Radcliffe and to the left a picture of Francis Smith of Warwick (mason) and to the right a bust of Gibbs.

Inside is a ‘stately’ Rysbrack statue of the munificent doctor, with the inscription ‘Johannes Radcliffe, huius bibliotechae, fundator’. The fine plasterwork is by master craftsmen such as Joseph Artari, Charles Stanley and Thomas Roberts, a local Oxford plasterer and the stucco ceiling is painted light blue, gold and white.

Above the bookshelves are busts of the giants of Greece, Hippocrates, Aristotle and so forth, and the views from the windows are striking, and because of their height, unusual. The ground floor — now the S T Lee Reading Room — is more workaday, with a slightly subterranean feel. It has a vaulted ceiling, containing the arms of Radcliffe and was originally an open arched arcade. The arches were fitted with iron grilles and entrance was through them.

But in 1863 the arches were glazed in and the area round the library part paved, cobbled and gravelled.

Iron railings were installed, to be removed in 1936 and subsequently, reinstated.

The opening ceremony took place in 1749, with the university giving George II a sycophantic address of congratulation on the crushing of ‘the most wicked rebellion in favour of popish pretenders’. But old sentiments lived on in Oxford, with a provocative pro-Jacobite speech delivered by Dr King — a speech that gained wide notoriety.

The library itself held a variety of books in the first 60 years, but from 1811 onwards only scientific books. There was also, at first, a collection of objects that included coins, marbles, busts, plastercasts and statues.

The visitor today sees many a sign in the Camera forbidding eating and drinking, but there have been at least a couple of occasions in the past when a banquet was the order of the day. In 1814, the Allied Sovereigns came to Oxford in what turned out to be a premature celebration of Napoleon’s downfall. The Tsar of Russia, the King of Prussia, the Prince Regent and the Duke of York joined Wellington, Blucher and Metternich for the conferring of degrees and the eating of banquets at the Library and Christ Church.

A contemporary diary of the occasion recounts much disorganised planning, with the local military practising with stones the passing of plates of food from Brasenose kitchen into the Library. And soon after, what an occasion it must have been when 4,000 people enjoyed dinner in the Square to celebrate the defeat of Napoleon! A later royal dinner took place more recently, with no doubt more planning and certainly fewer dishes than in 1814.

In 1988, Prince Charles came to highlight the plight of the Bodleian Library, and the meal was limited to three courses. The scenic qualities of the Radcliffe Camera, surrounded as it is by other fine buildings such as the Bodleian, Brasenose College and All Souls, are an ever appealing setting for television and film. In the Inspector Morse episode, The Daughters of Cain, a bloodstained bicycle is found against the railings of the Camera, and the familiar red Jaguar is parked in the square in several other episodes. Perhaps the greatest architectural contrast in the square lies between the Radcliffe Camera and St Mary’s — the one religious, rectangular and gothic; the other secular, circular and 18th century. Both are self-confident in their design and purpose and seem well able to accommodate each other.

In 1927, the freehold of the building and the land passed from the Radcliffe Trustees to Oxford University and the science books moved to the university museum and then to the Radcliffe Science library. Now the Camera is a library for English, History and Theology, plus papers and periodicals.

The best time to see the Radcliffe Camera is at twilight, with clouds racing across the lead dome, the lanterns lit, the cobblestones of the square shiny and often wet. John Radcliffe may have been ‘very ambitious of Glory’ but his magnificent bequest has given Oxford University the only formally planned space that it has ever possessed, as well as a wonderfully romantic library, the architectural triumph of James Gibbs.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article