Who was the greatest dictionary-maker ever? Most people, faced with this question, would instantly think of Dr Samuel Johnson.

Yet, pioneer though Johnson undoubtedly was, it is Scottish lexicographer Sir James Murray, the first editor of The Oxford English Dictionary, who deserves this accolade.

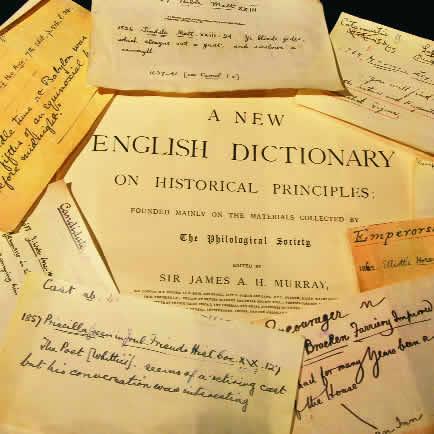

It is James Murray’s dictionary — first produced in 125 unbound volumes between 1884 and 1928 — that has earned global recognition as the most authoritative guide to the English language.

Uniquely, it charts the changing definitions of words from 1150 onwards, with illustrative quotations for each century of usage, as well as information on spelling, pronunciation and dialect.

Murray devoted more than 35 years of his life to this colossal project, of which 30 were spent at 78 Banbury Road, where he lived from 1885 until his death in 1915.

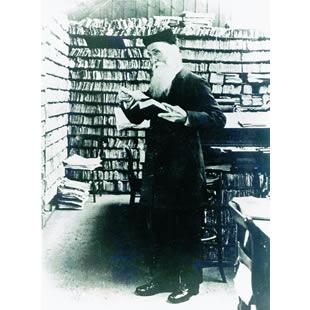

One of the first things he did after moving in was to build a rather unsightly, corrugated-iron shed in the grounds, close to the house. This became known as his Scriptorium and here he would work from early in the morning to 11 at night, standing at his sloping desk as he patiently inscribed every word in a neat, microscopic hand.

The Scriptorium has long since been demolished but the post-box erected to cope with the tide of correspondence engendered by the dictionary still stands outside the house, not far from the blue plaque.

Perhaps one of the most fascinating aspects of Murray’s achievement is that it was largely unplanned. His chief passion was teaching and for many years he pursued his love of linguistics purely as a hobby. He was 48 when he reluctantly gave up teaching to concentrate on the project that would earn him a place in the history books.

“Everyone who speaks English owes Murray an unpayable debt,” proclaimed novelist Anthony Burgess, who also described Murray as: “a magnificent man — one of the finest human beings of the 19th century.”

So how did a lad from a humble Scottish background come to be involved in one of the greatest linguistic projects of all time? He was born James Augustus Henry Murray on February 7, 1837, in the village of Denholm, near Hawick, Roxburghshire (now Scottish Borders).

His father was a tailor and the young Murray seemed destined to follow in his footsteps when poverty forced him to leave school at 14 and learn his father’s trade. But his academic gifts, apparent from an early age, secured him an assistant schoolmaster’s post at Hawick United School when he was only 17. Murray devoted the next 30 years to teaching.

During this time, he gained a BA degree from London University as an external student and established his reputation as a linguistic scholar with the publication of Dialects of the Southern Counties of Scotland in 1873.

He also had to cope with a double tragedy — the death of his seven-month-old daughter in 1864 and, a year later, that of his first wife. But his strong religious beliefs helped him through and eventually he found happiness with his second wife, Ada, with whom he had 11 children.

In 1878, Murray was appointed president of the Philological Society of London, a post he held for two years and resumed for a further two years in 1882.

It was his membership of this society — whose members, incidentally, included phonetician Henry Sweet, the model for Shaw’s Professor Higgins in Pygmalion — that led to his involvement with a project to produce a concise English dictionary for Macmillan and American publishers Harper & Co.

This dictionary was a watered-down version of a project conceived in 1857 by society members Richard Trench, Herbert Coleridge and Frederick Furnivall, who began collecting material for what they envisaged as the most comprehensive and informative survey of the English language ever. The idea was to replicate Samuel Johnson’s use of quotes to illustrate word meanings but to go a step further by incorporating the life history of each word — an idea spearheaded by German lexicographer Franz-Passow in 1812.

The Macmillan-Harper project eventually collapsed, mainly due to mismanagement by Furnivall, who had taken over the editorship in 1861. But it was resurrected in 1879, when Oxford’s Clarendon Press agreed to take it on.

This time the dictionary was to be a much larger-scale work, originally envisaged by Trench, Coleridge and Furnivall. Clearly, the editorship needed to be entrusted to someone of exceptional scholarly ability and Murray seemed the obvious choice.

By this time, Murray was teaching at Mill Hill Grammar School in London, and agreed to take on the work in his spare time — a misguided and somewhat fanciful expectation, as he soon discovered.

In 1885, the demanding workload forced him to leave Mill Hill and he moved to Oxford to devote himself full-time to the dictionary.

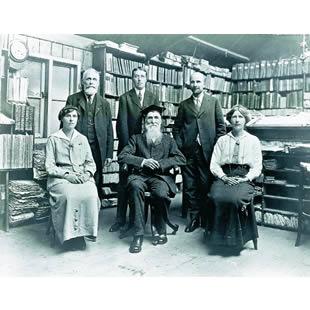

He was helped by a team of poorly-paid sub-editors and researchers, as well as a global army of volunteers, both amateur and professional, who undertook the tedious task of scouring books for words and delivering them to Murray for inclusion in the dictionary.

Bizarrely, one such volunteer was Broadmoor inmate William Chester Minor, a former army surgeon convicted of murder, who contributed more than 12,000 quotations. When Murray died in 1915, the dictionary was far from finished.

Work continued under the editorship of Henry Bradley, one of Murray’s official collaborators, and was completed in 1928.

Almost immediately, it was reissued in ten bound volumes and a complimentary copy was sent to George V. The finished work ran to around 15,500 pages, of which Murray had written almost half.

Murray was rewarded with a knighthood (1908) and several honorary degrees, including two from Oxford.

A blue plaque at 78 Banbury Road, Oxford, was unveiled in November 2002, 87 years after his death, ensuring his continuing recognition in the city that became the setting for his greatest achievement.

To find out more: read Caught in the Web of Words (1977, ISBN 0 300 02131 3), by KM Elisabeth Murray, James Murray’s granddaughter.

Photographs from the Oxford University Press archives are reproduced by permission of the Delegates of Oxford University Press

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article