For centuries the great and the good in Oxford had an aversion to washing on the grounds that it opened the pores and let in diseases such as cholera, typhoid or smallpox. Indeed it was the great, including dons and doctors, who went unwashed just as much as the people Thackeray famously described as the Great Unwashed.

For instance the 17th-century Oxford scientist and architect Robert Hooke seldom washed any part of himself other than his feet; and even King James I, whose clothes were rotting, must have been fairly rank when he visited the Bodleian in 1620.

The fact that there was a tax on soap until 1853 did not help matters either.

Only in the late 18th century and early 19th — probably in the wake of spas and sea bathing becoming fashionable — did the idea gain credence that washing was wholesome and that open pores let poisons out rather than in.

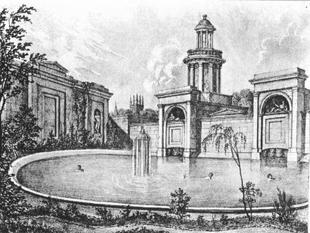

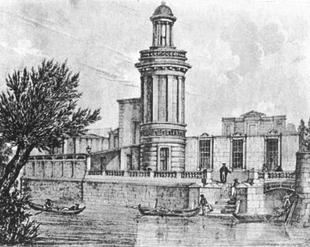

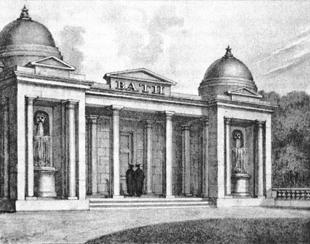

Bath Street, in East Oxford, is so named because St Clements Bath was opened there in 1827. The proprietor was a Mr A.H. Richardson, whose grand plans were illustrated in Nathaniel Whittock's illustrated book of Oxford buildings published a year later. The designs for the baths included a splendid portico for the street entrance, and steps down to the river for the use of customers arriving by boat.

But whether the baths were ever actually built in so grand a manner is a moot point. Graeme L. Salmon, in his excellent book Beyond Magdalen Bridge: The Growth of East Oxford (Oxford Meadow Press, 2010) writes: “The grand classical facade was probably never built. Inside the cover of a Bodleian copy of the prospectus is a manuscript note from 1907 indicating that a Mr T.J. Carter who had lived in New Street opposite the baths for 60 years did not remember seeing the elaborate facade.”

In any case, the baths never gained the hoped-for popularity and they closed in 1877. But while they lasted they contained: plunging baths, dressing rooms, warm baths and showers, a saloon complete with periodicals and newspapers, and a swimming school, quaintly described in the prospectus as a “School of Natation”.

Mains water came to Oxford comparatively early. In the 17th century, a London lawyer called Otho Nicholson devised a system for catching water from springs above North Hinksey and sending it to his elaborate Carfax Conduit in the city centre via lead pipes.

His system replaced an earlier one devised by the monks of Osney in the 13th century which had fallen into disrepair Nicholson’s North Hinksey Conduit House, with its original 17th-century roof over a reservoir, is now in the the care of English Heritage.

The Carfax Conduit, dating from 1617, was given to Lord Harcourt in 1787 after it became a traffic hazard. It now stands as a sort of folly in the park at Nuneham Courtenay.

A sewage system of sorts existed in Oxford in the early 19th century; but all the drains emptied into the Thames or its tributaries. Unsurprisingly, cholera was a constant threat.

There were serious epidemics in 1832, 1849, and 1854.

But things were evidently less bad here than in London where the Great Stink occurred in the hot summer of 1858.

So bad was the smell that plans to move Parliament and the Law Courts to Oxford only failed to materialise because the weather broke. Disraeli, then leader of the House of Commons, described the Thames as “a Stygian pool reeking with ineffable and unbearable horror”.

Not until John Snow, a London doctor, proved that cholera was communicated by water infected with sewage, rather than being carried on the air, was clean water taken seriously. An efficient sewage system was put in place in Oxford in the 1870s.

But washing continued to be viewed by some with suspicion. I remember hearing of an elderly — and presumably smelly — don in the early 20th century who reckoned that washing destroyed “the natural oils”. One of his pupils told me that the soap in his room needed dusting every now and then.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article