Sitting in the garden of her home just outside Witney, our woman in Basra cheerfully declares she is someone who enjoys the heat.

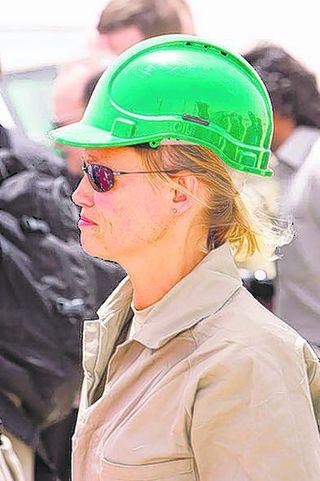

The spring sunshine beating down on West Oxfordshire hardly compares to what Alice Walpole will soon have to endure when she flies back to the compound on Basra Airfield, where she lives and works as Britain’s Consul-General in southern Iraq.

Nor can her home in one of the loveliest villages in the county be easily compared with the rocket proof, windowless, shipping container, encased in concrete, where she lays down her head for most of the year.

Inside the house, that she will shortly be leaving after a break in the UK of less than a week, her 16-year-old daughter is revising for her GCSE exams. Isobel is the third of her six children, and the fact that Ms Walpole is a single mother, makes it all the more remarkable that she is prepared to dedicate herself to one of the most daunting and dangerous jobs any British diplomat could face.

The compound in Basra at the airport, formerly the British base in Iraq until it was handed over to the US military last year, repeatedly comes under rocket attack. When she travels out of the base she often has to be accompanied by as many as 14 protection officers, with the enduring risk of explosive devices on roads and kidnap when travelling ‘down town’.

“Someone is with me all the time. Even if I just go to the American military shop on the base, a protection officer will be standing next to me while I’m picking out a shampoo.” she says. “I’m very well looked after. Security is taken very seriously. We all have body armour and do various drills.

“If I go anywhere it is carefully prepared. I travel in an armoured car. If something does not feel right, we don’t do it. We are now in a post-conflict situation,” she says. But the sound of a bomb going off in Basra Market Square last month, killing at least nine and wounding 50 more, could be clearly heard in the base.

Her description of a recent social event at the base confirms that this is a Foreign Office posting like no other. “We had a barbecue last month with a quiz afterwards. We had about 70 people there — all the people who work for me, members of the international business community and so on.”

But suddenly they were all faced with responding to the same thing, with the sound of an incoming rocket. “Everyone dropped to the floor in the space of three seconds, without anyone saying anything. Some people were lying comfortably on the ground, still holding their plates and drinks. It was very impressive. But there are nothing like the same number of rocket attacks that there used to be. My predecessor had to live through several a day. There are now a couple a month, although there have been slightly more since the election in March.”

It seems Thursday evening is the most dangerous time. Some thought the attacks were timed to coincide with outdoor film night at the compound. Ms Walpole believes there is another even more cynical explanation. “I think it happens so that they have some videos to show in the Mosques the next day.” The Foreign Office outsources its security to a private company, which employs mainly ex-army officers and police officers, all armed and with vast experience of working in the region. “Whenever I go anywhere, I’m always hoping that I’m taking them somewhere that they have never been before. But I’ve only managed to do it once.”

In the morning, two members of the team will be shaved and showered ready to accompany the boss on a 8km run around the base, with the route taken now well established. “We have to take precautions when you go for a run. I know places to take cover everywhere along the route.”

Running around the compound? It almost sounds like an open prison. “More like a closed prison,” she corrects me. “But everyone has chosen to be there. The atmosphere is good. It’s a small well integrated community. Whether they’re kitchen staff, forensic experts, protection officers, youth employment experts, diplomats or police officers they are all part of the team. We eat together, we play Wii bowling together.”

When we met, Ms Walpole was already planning to turn the World Cup into a major event, with the American military staff joining her team for an outdoor showing of the England USA clash. Some Iraqis would also be invited to attend.

“The Iraqis love football and Iraq is not in the World Cup this time. I’m hoping to get them on our side” — a challenge that in fact takes up much of her life, and is set to continue to do so. The 46-year-old diplomat tells me that she has just agreed, after a year there, to extend her stay in Basra by a further six months, taking her well into February. “Yes, it can get wearing. But that is why we come back on breather breaks. I’m only back home for a few days this time to be home for half term. But the idea is that you work six weeks then have two weeks off.”

For all the rockets attacks and 11kg of body armour she must wear in downtown Basra, the hardest part of the job is leaving her children behind. Her departure this time would be particularly painful, with the day of her departure falling on the 14th birthday of her son Inigo, a scholar at Winchester College.

She has had other foreign postings in Tanzania, New York and Brussels, but the Basra job is the first time she has been unable to take her children with her. She insists that she would not have gone to Iraq if the posting had caused any of her children serious upset. “If any one of them became worried or upset I would stop doing it. What really matters to them is having information. They know I fly around in a Black Hawk helicopter. They can picture it in their minds They have seen pictures of the pilot who flies me. It is important to take away the mystery.”

Ms Walpole separated from her husband, a senior civil servant at the European Commission in 2002. But at least now, she says, her two eldest children Hester and Beatrice are grown up and at Oxford University, studying at St Hugh’s and Lady Margaret Hall, respectively. Having her children at a young age means she now has greater freedom, she says, but she still worries about her ten-year-olds Ralph and Edmund, who attend an Oxford boarding school. Until a year ago we lived in London. But I decided to move out, so that when we meet up it would be somewhere more relaxed and close to their school. The advantage of the job that I’m doing, is that it does not mean having to fly across the globe. It is not terribly far.”

She arrived in the south shortly after the British military moved out, to face the daunting task of heading the British contribution towards helping the province get back on its feet. Britain is the only country, other than Turkey, to retain a diplomatic presence in what is Iraq’s principal oil hub and business centre, giving UK companies unique opportunities and access, she argues.

“The theme of my whole career is dealing with conflict and working in post conflict situations. I knew this mission would test every experience I’ve ever had.” But the role of attracting as much international business into the province, and assisting British companies in any way she can, is new to her.

“I now know a lot more about the oil industry,” says Ms Walpole. But she shakes her head, when I suggest that the sight of British companies moving in will only confirm to opponents of the war, what the invasion was really all about.

“I was at the United Nations from 2001 and know why we got involved and it wasn’t about oil. I do not believe that any government is going to accept casualties for economic gain. You do not sacrifice people for oil. What is quite clear is that Iraq’s economy hinges on exploiting their oil wealth. And they can’t do that completely by themselves. One of my roles is put the best possible partners alongside them and British companies are among the best in the world. That is sensible.”

In addition to businessmen, there are regular meetings with religious leaders, tribal sheikhs, students and academics. But doesn’t being a young woman get in the way of her work in this part of the world? “It is a non issue,” she replies. “Sometimes if I’m visiting a Muslim in their office I cover my head with a scarf. A number of sheiks will not shake hands with a woman. But that is fine. Whereever you live overseas there are people of different cultures.”

She is working hard to support the creation of a museum in Basra for local antiquities, with the British Museum providing the expertise. It will go into a small palace that had been built for Saddam Hussein. She is also involved in efforts to develop an archaeological facility at Basra University.

While her countrymen and women have had their minds focused on the closest British election in years, Ms Walpole, a descendant of Britain’s first Prime Minister and whose mother Judith Chaplin was a Tory MP for Newbury, was carefully observing the altogether tenser elections in Iraq. Three months afterwards, Iraq still does not have a government as the various coalitions within coalitions struggle to reach agreement. But she is happy to declare that the elections, for which so many have died, were at least fair, even if the outcome is far from settled.

“I saw people exercising their democratic right to vote. The election makes Iraq the second most democratic country in the Middle East,” she said.

You sense such optimism, and desire for signs of momentum, are needed as she turns out the light inside her concrete-encased container. Now our soldiers are gone, Alice Walpole is still out there trying to win some kind of peace.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here