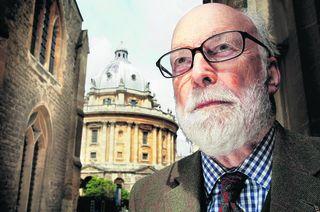

Having spent many years scrutinising just about every major development in Oxford, Mark Barrington-Ward has decided it is high time to focus on the contents of his own loft.

It is more than three decades since Mr Barrington-Ward sat in the editor’s chair at the Oxford Mail, but since retiring 17 years ago he has continued to be a major player in shaping the development of the city that has been his home since 1948.

Last year alone, on behalf of the Oxford Civic Society, of which he has been president since 2004, he examined almost 3,000 planning applications, to spare the city from various eyesores, carbuncles, sprawl and repeating the mistakes of the past.

But at 82, this staunch protector of Oxford’s heritage will be addressing matters a little closer to home.

“I must sort out all the family papers that I have accumulated in my loft,” he told me, when we met at his Apsley Road home in North Oxford. “It is something I’ve been planning to do for years and I know I no longer have infinite time for other projects.”

Organising family papers in Mr Barrington-Ward’s case will be a major task. For his father was the distinguished journalist R.M. Barrington Ward, who edited The Times from 1941 to 1948.

An influential figure during the bitter debate over appeasement and during the Second World War, R.M. Barrington Ward recorded events about his life on The Times and his meetings with Winston Churchill and other major figures in a diary. Hardly holiday snaps and old school reports; no, the contents of the Barrington-Ward loft are the stuff of history.

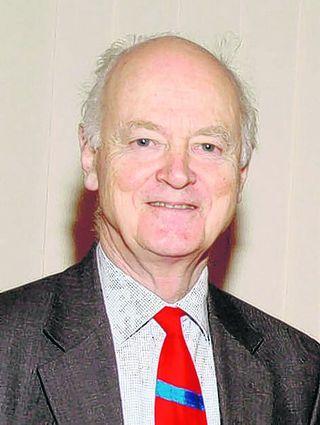

At least he will stand down as president happy in the knowledge that the presidency of the Oxford Civic Society will pass to a trusted figure, whose love of Oxford’s past and concern for its future matches his own.

For he is to be succeeded by Sir Hugo Brunner, who, as Lord Lieutenant of Oxfordshire between 1996 and 2008, became one of the most familiar faces in the county.

The man many said had left a pair of shoes impossible to fill as the Queen’s representative in Oxfordshire, is now himself faced with the challenge of having to follow a class act.

The society concerns itself with trying to protect the quality of Oxford’s built environment and its impact on people’s daily lives. In recent times it has been involved with keeping the Museum of Oxford open, running the blue plaques scheme commemorating sites of historic interest and in organising the OxClean campaign, which sees hundreds of volunteers taking to the streets of Oxford every March to give their city a spring clean. The society was formed 40 years ago by Oxford citizens outraged at the prospect of traffic-attracting proposals to build inner relief roads in the city and angry about the wholesale clearance of St Ebbe’s and the creation of the “jumble of buildings” that formed the centre of Blackbird Leys.

The retiring president sets out the society’s achievements, while highlighting the highs and lows of town planning in Oxford in a newly published booklet Forty Years of Oxford Planning: What Has It Achieved and What Next?

“You might say it is my swansong,“ said Mr Barrington-Ward, pointing to the cover featuring two photographs of Radcliffe Square; one showing the historic square as a rat-run, congested with traffic queuing up alongside the Radcliffe Camera, the other showing the scene as it is today, with Catte Street paved and students strolling into the unclogged golden heart of Oxford.

The message is clear; change has not been all bad.

Mr Barrington-Ward has always taken the view that when it comes to town planning, successes soon come to be taken for granted, while failures continue to be held against planners for years.

Then there is the constant refrain that the city is simply not what it was, when, in fact, for much of the 1960s snarl-ups in the city centre were the norm, with cars belching fumes and queuing bumper-to-bumper in Cornmarket. For then, as now, the most notorious single issue had been to reduce the traffic pouring through the city centre.

In fact, Mr Barrington-Ward’s booklet traces problems all the way back to 1934, when Oxford’s first traffic lights were installed at Carfax, the spot where east-west traffic crossed the path of north-south traffic, causing long lines of stationary vehicles to form in High Street, Queen Street, Cornmarket and St Aldate’s.

“The disadvantage, as the city grew, has been that the main shops, the town hall and the railway station were in the western half of Oxford, while most of the houses built for the families of workers in the expanding car industry at Cowley were in the eastern half,” he maintains. “For a long time the only link between them was across Magdalen Bridge, which funnelled traffic along the High, the city’s finest street.”

Easy to diagnose the problem, but the agonising bids to find a solution have been the stuff of a 40-year nightmare, with the most notorious proposal being a relief road for the High running across Christ Church Meadow; either as riverside boulevard, or close to the college, or right across the middle. An alternative idea involved two crossings of the Thames, through Eastwyke Farm, where Oxford Spires Four Pillars Hotel now is.

The Christ Church Meadow idea, which famously went to Eden's Cabinet in the middle of the Suez Crisis, we learn from Mr Barrington-Ward, was a close-run thing.

Another less-well-known proposal apparently given serious thought involved taking to heart the old joke about “Oxford being the Latin quarter of Cowley”. For it involved the idea of making Cowley Oxford’s main shopping centre in order to save the historic city centre, with a new civic centre in St Clement’s.

The ‘twin city’ concept was soon branded “an escapist dream”.

It was dead the minute the city council lost its fight to prevent Woolworth’s from knocking down the historic Clarendon Hotel for a new store in Cornmarket. Marks & Spencer then had to be allowed to rebuild as well.

But there is plenty to highlight on the credit side: the shift to restraining traffic in the university area, which began in the 1970s with the closure of Radcliffe Square, New College Lane and Holywell as through routes; the city council’s adoption of a high buildings policy, which allows only small-scale additions to the skyline; and the protection of the city’s green views.

Mr Barrington-Ward even insists that it is too simplistic to view what happened to St Ebbe’s as simply being the smashing up of a community at the behest of commercial interests.

“In lamenting the extent of the destruction in St Ebbe’s it is easy to overlook what was one very positive achievement of the planners, the removal of the gas works from both sides of the Thames,” he writes. “The gas holders no longer impinged on the famous skyline and Oxford’s riverside was gradually redeemed.”

As for the Oxford Civic Society, he has no doubt about its greatest contribution to the welfare of the city: it is the creation of park-and-rides in Oxford, as a positive alternative to inner relief roads.

They were introduced in the 1970s in defiance of experts and Whitehall, with Mr Barrington-Ward back then far from initially convinced that they would work without at least some city-centre road-building.

“On the whole I think things have improved,” he said. “But we have seen things that could have been done better. But it is easy to see change as the enemy.

“One of the attractions of living in Oxford is that it is not a museum frozen in time. It has adapted to changing needs, offering a spectrum of modern architecture to add to the old. There is no better proof than the St John’s College Garden Quadrangle.”

He first arrived in the city in 1948 to read history at Balliol, after national service in the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. Having started in journalism on the Manchester Guardian in 1951, he first became a political correspondent before going out to Kampala to launch the Uganda Argus, the country’s first modern English language daily paper.

After a brief spell editing the Northern Echo, he returned to Oxford in 1961 to become editor of The Oxford Times’s sister paper, a position he held until 1979.

A milestone in his editorship was the move from the offices in New Inn Hall to Osney Mead. Few regional editors could claim to have such a knowledge of architecture and inevitably he took a keen interest in the design of what was then viewed as a ground-breaking open-plan building, which was to win a Civic Trust Award and was commended by the Royal Institute of British Architects.

If the city could reward his service to heritage by allowing him to abolish a single building, I wondered which it would be?

“The former telephone exchange building at the back of Oxford Crown Court, which was built in the 1960s,” he replied, without hesitation.

Rather than working his way through a list of other 1960s eyesores, however, he insisted it was a mistake to condemn all 1960s structures.

“In my youth there was a similar blanket reaction against Victorian buildings. There are sixties buildings that I quite like, such as the Blackwell’s headquarters in Hythe Bridge Street.”

The big challenge facing the city today, he argues, is how best to meet the shortage of affordable homes. But he fears the implications, particularly for the Green Belt, if affordable homes are built as “a by-product of the fits and starts of private development”.

The risk is that the poor planning and lack of infrastructure seen in the 1960s could yet be repeated.

He finishes the book with a challenge: “If Bicester can have an eco-town extension, should not Oxford aim to have an extension, if it has to have one, built and designed to a high standard, produced in effect like a mini new town?”

Vigilance will still be needed. That is his advice to the city.

And before he immersed himself in his father’s diaries, did the great old newspaper man have any thoughts on modern journalism on the eve of the election?

“Well,” he began, “I once wrote that anyone writing newspaper history should always remember the fable of the fly that thought it was pulling the coach because it was riding on the horse’s back.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here