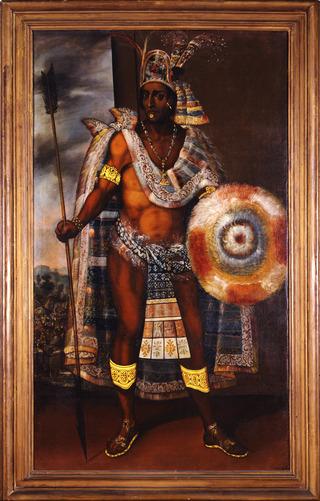

There was a moment not far into the Moctezuma exhibition when the mystique and absolute power of this last elected Emperor of the Aztecs struck me. I had walked past a map showing Moctezuma II’s empire stretching across much of central Mexico, from the Gulf coast to the Pacific, and learnt how he had consolidated control over a politically complex empire with his tyrannical rule and military prowess. I had seen Moctezuma portrayed as a magnificent warrior resplendent with spear and shield, gold ornament and feathered headdress, in a portrait by the Spaniard Antonio Rodriguez (see above) painted 150 years after his death.

By early on in this engrossing show – the fourth and last in the BM’s chronological series on great rulers – I had put right a few misconceptions, one that the ‘Aztecs’ are more correctly called ‘Mexica’ (pronounced ‘Meé-shee-ka’), I had learnt that Montezuma spelt with an ‘n’ is an anglicised form that apparently sounds odd to Spanish ears, and was familiar with the Mexica civilisation’s foundation myth. An eagle had landed on a cactus, as was foretold, on the very spot the Mexica then made their capital, Tenochtitlan, on an island in Lake Tetzcoco in 1325. (The eagle on a cactus symbol is on the Mexican flag).

But then the utter tyranny of this supreme ruler struck me again. I saw a large carved eagle stone, the eye-catching sculpture striking under a spotlight. I moved closer to inspect the damaged eye and beak of this symbol of the sun in ancient Mexico, and saw that its back was hollowed out. Reading the display (the exhibition is very clearly explained) I read that the cavity once held the hearts of humans sacrificed to feed the sun, and that the Eagle Vessel was found next to the Great Temple, the huge four-sided stepped pyramid in the heart of Tenochtitlan where human sacrifices were carried out.

Moctezuma II would regularly have performed blood-letting rituals. Such rituals maintained cosmic order and the well-being of the people. He also sacrificed captives, sacred warfare being requisite for rule.

Moctezuma reigned from 1502 to 1520, the ninth ruler of the Mexica. He came to power ten years after Columbus voyaged to the Americas, and seven years before Henry VIII came to the throne of England. Charles V ruled Spain from 1516-1556. Moctezuma’s reign ended, however, with his death a year after the Spaniard Hernan Cortes arrived with a few hundred men on the Mexican coast in 1519. Within three years, Tenochtitlan and the Aztec empire had fallen. Moctezuma’s fame rests on his losing an empire. The exhibition explores both Spanish and indigenous versions of the invasion. Also the dual nature of his fame: an ambiguous figure in Mexico today, he’s mostly seen as a tragic figure who ceded his empire to foreigners, but also as a successful warrior.

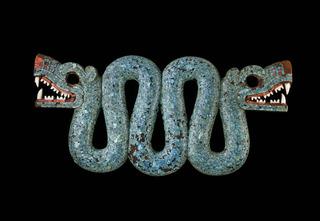

Cortes was fired by lust for gold, as well as glory and Christian zeal. When he first landed, Moctezuma sent emissaries with precious gifts of gold, turquoise greenstone and so on. Cortes gave Venetian glass beads in return. There are items here that are the sort of goods that may well been part of that initial exchange. One example is the gorgeous double-headed serpent (c1500-1521) made in wood inlaid with a mosaic of turquoise and shell. Others are the gold turtle necklace, the finger rings, or even a feather fan. Of necessity, Moctezuma’s history and that of his empire is a mostly retrospective account, seen through European eyes. Most books and other pictorial sources were destroyed during the Spanish conquest. A rather gaudy series of oil paintings on wooden panels inlaid with mother of pearl that glorify the conquest were made 200 years after the events they portray. These ‘enconchados’ depict scenes such as Cortes approaching Tenochtitlan on horseback, him dining with Moctezuma, the captured Moctezuma in irons (in the background citizens pull down a Christian cross), and one showing Moctezuma stoned to death by his people (the Spanish version of his death). Many objects were refashioned after the conquest, and some put to Christian use, such as the stone sculpture of Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, one of their most important gods, remade into a baptismal font. You can still just see the god’s feathered coils on the underside.

The British Museum has done a really good job with this exhibition. It is informative, a manageable size, and well displayed. The iconic objects on loan from Mexico (including some newly excavated material) and Europe have mostly never been seen in this country before. Furthermore, there are some wonderful sound effects!

As I walked through gazing at objects, from ordinary stone cactus boundary markers to extraordinary jewellery and priceless codices, I could hear the screech of eagles soaring overhead and the wind howling around the temples and mountains. It was tremendously evocative.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article