Oxonmoot is always a highlight of the Tolkien Society's year. Held to mark the birthdays of Bilbo and Frodo, hobbit lovers from across the world gather at an Oxford college to enjoy academic talks, masquerades (costume is optional) and drink tea with old and new friends.

This year Oxonmoot 2009 is being held at Lady Margaret Hall from September 25 to 27. On Sunday, the lectures and merriment will be interrupted for a wreath laying and short act of remembrance at J.R.R. Tolkien’s grave in Wolvercote cemetery.

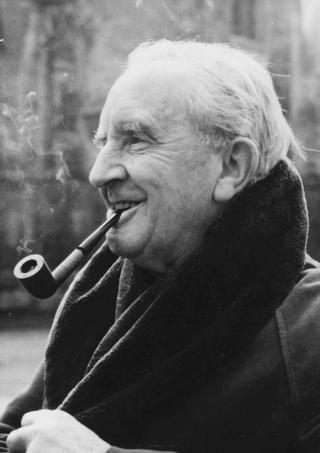

Doubtless, some will be speculating whether the late Oxford University Merton Professor of English Language and Literature is turning in his grave at the prospect of his classic work The Hobbit becoming the subject of a legal battle in the Los Angeles Superior Court.

For the great author would surely have hated the idea of his two children, Priscilla, who lives in Summertown, and Christopher, both in their eighties, having to take on a Hollywood film company over the rights to Middle Earth.

In his own lifetime, Tolkien had some bad experiences at the hands of American film-makers and a book publisher, who printed The Lord of the Rings without permission and without paying royalties.

But such irritations hardly compare with the difficulties now facing the heirs of his estate, who find themselves up against New Line Cinema, a subsidiary of Time Warner, who they say have not paid up a penny of the millions of pounds owed to them from the film versions of The Lord of the Rings.

At a time of life when Miss Tolkien, a former probation worker, and her brother must surely have been expecting to be enjoying peaceful retirement, they find themselves as plaintiffs in a hugely complicated lawsuit. The Tolkien Trust maintains that £130m is owed in compensation for unpaid profits from The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, one of the most successful movie projects in history, said to have made £6bn in box office receipts, DVDs and merchandise.

As reported in last week’s The Oxford Times, the outcome of the case could have major implications on the two-part film adaptation of The Hobbit, in Hollywood parlance the prequel to The Lord of the Rings, which is already in pre-production in New Zealand.

For, while the family say they are not setting out to deliberately derail the eagerly-awaited films, their lawyers will argue that the company has forfeited its rights to make those films because of “its breach of contract in failing to pay even one cent of the millions of dollars owing to the trusts from the three The Lord of the Rings films.”

The Tolkien estate has contributed millions to charity in recent years. And the family’s lawyer Steven Maier, a commercial litigation partner with the Oxford law firm Manches, made plain that the heirs of Tolkien view it as a fight they simply can’t walk away from.

“The trustees are appalled by New Line’s attitude to their legal obligations and are determined to pursue their claims to their rightful conclusions.”

Los Angeles will strike many as an unlikely place to stage a struggle for the ownership of Middle Earth, the world Tolkien created as an alternative to a modern age being overrun by polluters, inveterate consumers and technologists.

But when it comes to litigation and fighting compensation claims, the trustees will find Hollywood attorneys as aggressive as stone trolls and as ruthlessly calculating as the wizard Saruman the White.

The root causes of the dispute, fittingly, are complex, surrounded by mystery and buried deep in the past, with J.R.R. Tolkien himself at the very heart of it. For the great Anglo-Saxon scholar, former First World War soldier and writing genius was not a man who greatly concerned himself with fame, money or Academy Awards. And as his official biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, observed, Tolkien was no businessman.

When on an unspecified summer’s day, bored with marking school certificate exam papers at his home at 20 Northmoor Road, in North Oxford (the only one of his six Oxford residences to be marked with a blue plaque), he picked up a page left blank, and wrote the words “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit,” it was for his and his children’s amusement rather than with publication in mind.

His son, John, who went on to become an Oxford priest and died in 2003, would recall: “It is quite incredible. When I think, when we were growing up, these were just stories that we were told.”

Father Tolkien also hinted at his unhappiness about them being embraced by the rest of the world. “Personally, when you’ve grown up with something, you don’t want someone else putting their finger on it.”

Tolkien himself certainly hated the idea of becoming a cult figure. He was also to have a bitter taste of commercial exploitation when one publisher thought it could take advantage of loose copyright laws between Britain and the USA to issue a paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings without paying out any money to its author.

In 1965, the Ace edition of The Lord of the Rings appeared in bookshops in America, on sale for a fraction of the original price, with the publishers apparently having no thoughts about paying the author any form of royalty. The dispute attracted considerable publicity and Ace was ultimately forced to agree to an out-of-court settlement to pay all royalties on future sales and make a lump sum payment for all the royalties they had withheld.

The current legal dispute can thus be said to be the second time that the Tolkiens have had to fight to reclaim Middle Earth As The Lord of the Rings became an international hot property, it was not long before his books were attracting the interest of Hollywood film-makers.

The first overtures came in 1957 when three American businessmen showed Tolkien drawings for a proposed animated film version of The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien was less than impressed to see that character names were misspelt in the proposal and that walking in the story seemed to have been dispensed with, everyone seemingly carried on the backs of eagles.

The idea was dropped, to the relief of many who believed Tolkien’s masterpieces was at risk of being turned into something childish and patronising.

But Hollywood was not to give up and in 1969 United Artists obtained the film rights, with Tolkien receiving £153,000.

The details of that contract, signed 40 years ago, which has been filed as evidence, looks like being pivotal when the case goes before the Superior Court in California on October 19.

It is believed that the author, who died in 1973, sold the rights for 7.5 per cent of future receipts and that under the terms of the 1969 agreement, gross receipts were to be paid after deducting 2.6 times the production costs plus some advertising expenses.

The production rights have since ended up with New Line, a unit of Time Warner. The company has declined to comment on the case. But one of its attorneys said in an email statement that the contract was ambiguous.

Another LA-based lawyer, Pierce O’Donnell, gave a clear warning as to what the Tolkiens would be up against when it came to taking on a movie giant.

“Usually it’s not outright thievery by the studios, but death by contract. It’s an esoteric world where black doesn’t mean black, and white doesn’t necessarily mean white.

“The studios have historically played hardball in litigation.

“Also these are hard times and they maybe think it’s cheaper to pay the lawyers than to pay a large claim. And maybe the lawyers think they have meritorious defences.”

On their side, the Tolkien Trust lawyers may seek to highlight over-inflated film company expenses and revenue left out of the final calculations, arguing that it is a case of Hollywood accounting in the extreme. There will also be disputes about foreign revenue, home video and television.

Bonnie Eskenazi, the trustees’ US counsel, who originally filed the complaint, earlier said: “New Line has brought new meaning to the phrase ‘creative accounting’. It will be certainly interesting to see how on earth New Line can argue to a jury that these films could gross literally billions of dollars and yet someone entitled to a share of gross receipts gets not a single penny. Should this case go all the way through trial, we are confident that New Line will lose its right to release The Hobbit.”

The Hobbit is already in pre-production in New Zealand, with a 2010 production schedule for the film. It is being directed by Guillermo del Toro, with Ian McKellen reprising his role as Gandalf. The former Dr Who David Tennant and Harry Potter star Daniel Radcliffe are among those said to be vying for the title role of Bilbo Baggins.

The film series already has a history of legal wrangling. The New Zealand film-maker Peter Jackson threatened to sue the New Line studio in a separate row over royalties from The Lord of the Rings, leading then studio chief Bob Shaye to declare that the New Zealander would never make The Hobbit. That dispute was settled in late 2007 and Jackson and his partner, Fran Walsh, were named as executive producers for the two Hobbit films.

The first exchanges in the War over Middle Earth have taken place, with both sides conducting ‘deposition interviews’ with the other side’s witnesses.

“The Tolkien plaintiffs are co-operating fully with that process,” said Mr Maier.

As a registered charity, the Tolkien Trust has given grants to good causes totally over £5m in recent years, and the outcome of the case could have major implications for local, national and international charities.

But for members of the Tolkien Society, of which Priscilla Tolkien is honorary vice-president (her late father is honorary president ‘in perpetuo’) the dispute is not about money or even the quality of the films.

If Middle Earth is J.R.R. Tolkien family’s gift to the world, it remains his family’s heavy responsibility to take on any commercial dragon, regardless of its size and treasure, to protect it.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here