This is an extract from the latest Court news: The Inside Scoop newsletter written by Tom Seaward which you can sign up to for free now.

On Monday, my Twitter feed was either videos of otters juggling stones (don’t ask) or journalists frustrated about the Attorney General’s warning to the media not to publish anything about Russell Brand that could prejudice future criminal proceedings.

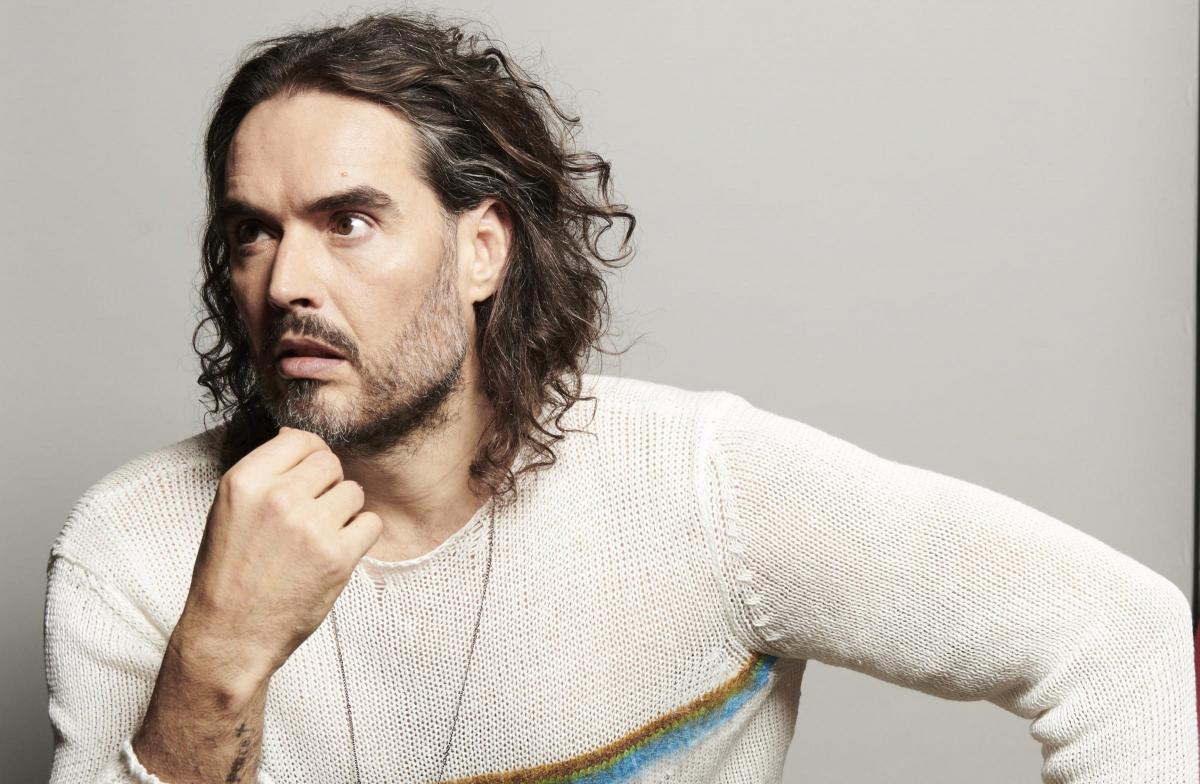

It came amid news that the Metropolitan Police was investigating criminal allegations against the comedian, who has been accused of sexual misconduct.

And the warning came in for criticism from journalists and university journalism course leaders alike.

READ MORE: Oxford Mail newsletters - The latest stories in your inbox

Contempt of Court Act rules don’t apply, they said, as Brand had not been arrested.

The case was not, to use the language in the law, ‘active’ and so nothing *could* be published that would have a substantial risk of seriously prejudicing the criminal proceedings – because there were no criminal proceedings.

That’s right. That’s what it says in section one of the act. It’s called the Strict Liability rule and, importantly, means you could be committing a contempt of court by what you publish even if you don’t intend to do it.

But as well as the Strict Liability rule, there’s another section of the law - 6(c) of the 1981 Contempt of Court Act - sometimes known as ‘common law’ contempt.

6. Nothing in the foregoing provisions of this Act—

(c) restricts liability for contempt of court in respect of conduct intended to impede or prejudice the administration of justice.

What does that mean in reality?

If you deliberately try and undermine a police investigation by posting wildly prejudicial details, for example, you could find yourself prosecuted by the Attorney General even if no one has been arrested.

The latest Court News: Inside Scoop newsletter from @t_seaward has been released today. 🗞️

— Oxford Mail (@TheOxfordMail) September 17, 2023

Sign up to the newsletter for free to get the analysis on the latest crime stories delivered directly to your inbox every weekend: https://t.co/tMegOuauq7 pic.twitter.com/Dyhgn4PEqN

One of the reasons why Victoria Prentis’ words fell on furious ears, though, is that it comes against a background where it certainly feels like the law is trying to make it harder to do journalism.

Last year, the Supreme Court ruled in a case called Bloomberg LP v ZXC that, in general, a person under criminal investigation has a reasonable right to privacy before they are charged.

Overnight, newsdesks and their duty lawyers were forced to re-evaluate what they could and couldn’t print.

A vast number of police investigations – some squarely in the public interest – will never make it to the charging stage.

Click the banner below to sign up to our Crime and Court Newsletter for free

Last week, new laws came into force in Northern Ireland that grant anonymity to people suspected of sexual offences until they are charged and will exclude members of the public from attending crown court during sexual offence cases (although journalists can attend).

Those investigated on suspicion of committing sexual offences – but not charged – will be allowed to retain their anonymity until 25 years after their death. Remember Jimmy Saville? Under these laws, the news of his horrific offending would not come to light.

The changes in the law follow a 2019 review by former top judge Sir John Gillen, who warned that having to ‘recite the most intimate and distressing details of their experiences before, potentially, a packed courtroom’ was ‘one of a number of factors deterring victims from engaging in the criminal justice system’.

The changes are limited to Northern Ireland.

However, the Law Commission, which looks into potential changes to the law, has published a new report proposing similar changes to how sexual offence trials are run in England and Wales.

It would include excluding all but one media representative from the court while an alleged victim is giving his or her evidence in sexual offence trials.

Unsurprisingly, the Crime Reporters Association has expressed its concern over the proposals.

I very rarely express an opinion in these emails, but I would just say this. The justice system is not just for victims, it is not just for defendants, it is not for the barristers, for the lawyers, for the police or the King.

It is for the public. It is how the public sees justice done, wrongdoing punished and the innocent acquitted.

For generations, that is something that has been recognised by members of the judiciary and its importance upheld.

In one of the most important cases for what’s called open justice, Lord Shaw in the 1913 case of Scott v Scott [1913] with approval philosopher Jeremy Bentham: “Publicity is the very soul of justice. It is the keenest spur to exertion and the surest of all guards against improbity.”

His words were echoed by Lady Hale (whose spider badge went viral), 103 years later in R (on the application of C) v Secretary of State for Justice – a Supreme Court case.

‘Publicity’, she said, had two main purposes: first, to enable public scrutiny of the courts, and second, to ‘enable the public to understand how the justice system works and why decisions are taken’.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel