What have Marsh Baldwin primary school, Oxford Castle, a churchyard in Cowley Road, Oxford University's Botanic Garden, 33 Northmoor Road and the ante-chapel of New College in common?

They all won Plaques in the 2007 Oxford Preservation Trust Environmental Awards, and surely none of the winners deserved recognition more than New College for the restoration of its ante-chapel stained glass windows.

As the Oxford Preservation Trust observed, this work has succeeded in protecting the glass without sacrificing its appearance, with spectacular results.

Dr Michael Burden, Fellow in Music at New College, explains that this has been no ordinary undertaking, but a project that has taken 20 years to complete, required great skill and cost in the region of two-and-a-half million pounds. The work has been paid for by private donations - many New College alumni subscribed - and supported by outside grants, particularly from the Pilgrim Trust and the Esme Fairbairn Foundation, two of the largest independent grantmaking bodies in the United Kingdom.

It is perhaps just one example of how New College likes to do things in style - and often on a grand scale.

Established by William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester, it is a foundation dating back to 1379. The correct' name for the college is St Mary College of Winchester in Oxford, but it has always been known as New College to distinguish it from an earlier St Mary College, now Oriel College. William of Wykeham was not only one of the most powerful, astute and political men in England, but also a man with a vision The decline in the university population following the ravages of the Black Death had severely reduced the number of available educated clergymen and servants of the state. New College was designed to answer the shortfall, and produce fit persons for the services of God in Church and State'.

New College really was new' in three particular aspects. First, undergraduates were taught inside the college rather than in the town. Second, William founded Winchester College as a feeder' school for New College, so that the senior institution should always have enough students entering with adequate knowledge of Latin and other subjects.

Third, and perhaps most important, the college was designed and built as a quadrangle. Within this quadrangle were all the main buildings required for the communal life of the college - the hall, library, muniment tower, bursary, Warden's lodgings and Fellows' rooms.

Until then, Oxford colleges, such as Merton, had grown without a masterplan. The layout of New College became the pattern for subsequent college foundations.

Today just off the north-east corner of the main quadrangle is a dark passageway leading to the cloister and to the chapel, the first major example of perpendicular architecture in Oxford.

Entrance is through a modest door. Open the door and the visitor is in a large ante-chapel, in days gone by big enough to accommodate small altars for private Masses, and to hold disputations and elections.

The first thing to be seen is a strange and mysterious eight-foot-high statue by Jacob Epstein of Lazarus, raised from the dead, but still bound in his burial bandages. Less striking are monuments to former college Wardens such as Robert Pinke and Dr Spooner, and fine floor brasses in a roped-off section of the north side. An immense memorial, some 30ft long, commemorates 263 New College students killed in the First World War.

Even more poignantly perhaps, a smaller memorial records the names of three college men who died fighting on the enemy side: In memory of the men of this college who coming from a foreign land entered into the inheritance of this place and returning fought and died for their country in the war, 1914-1919'.

High up in the south wall are a couple of spy holes, so that the Warden of the day could watch from his room the chapel comings and goings of his students and his Fellows.

And then there is the great West window. Originally, the window contained the Tree of Jesse, depicting the genealogy of Christ, a popular subject in medieval art. The original glass though was removed in the 18th century and sold to York Minster, reputedly for £30, where parts of it can be seen today.

The window was replaced by another design by William Peckitt, who carried out much work in the chapel and ante-chapel. But the Fellows disliked it so much that in 1799 yet another West window was commissioned. Designed by Sir Joshua Reynolds and executed by Thomas Jarvais, it depicts the nativity, and over the years seems to have been liked and disliked in equal measure.

The top half shows the crib in light surrounded by darker shadows and figures, including likenesses of Reynolds and Jervais as shepherds and Eliza Sheridan - wife of the dramatist - as the Virgin Mary.

The seven virtues in the bottom half of the window were also modelled on fashionable women of the day. These figures, in their diaphanous robes, represent Faith, Hope, Charity and the other virtues.

Thus Temperance holds a water ewer, Fortitude has a lion and Justice a sword and scales. They looked, according to Lord Torrington, like half-dressed languishing harlots'. Others though have found the virtues charming.

The painted glass is awash in brown, and russet and saffron and varying shades of grey.

It is effectively a transparent oil painting and an altogether surprising window to see in William of Wykeham's great devotional chapel.

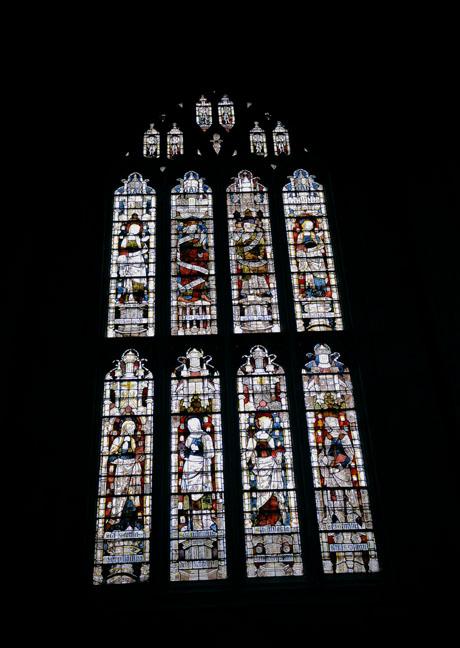

Very different are the surrounding religious figures in the other seven windows of the ante-chapel, the windows now restored over so long a period.

Though incomplete, they constitute one of the largest survivals of medieval glass in situ in England, and are of the greatest importance to historians and artists alike. They were designed and carried out between 1380 and 1386 and almost certainly by Thomas of Oxford, or Thomas Glazier as he is called in the New College archives.

Unfortunately, the building accounts for the foundation period have not survived, so there are no records of payments to Glazier for the stained glass. But what New College archives do show is that he is recorded several times over a period of years in the Steward's Book as dining in Hall.

As Jennifer Thorp, the present college archivist points out, Thomas Glazier must have been important to the college to be invited so often to dine with the Warden and Fellows. He also worked for William of Wykeham at the new school, Winchester College and in other buildings associated with the bishop, such as his residence at Highclere.

Glazier, in the judgement of stained glass historians, with his sophisticated eclecticism', knowledge of developments in the continental style of painting (however gained) and in his deployment of proportion and posture, was a master of medieval stained glass and the major influence in England of his time. He was also a busy man. With such a large output, commissioned over 40 years, he must have had some sort of workshop, no doubt with other glaziers as his associates and assistants.

So the chapel and its glazing was about complete by the time the Warden and Fellows took possession of New College in 1386.

On entering the ante-chapel, the visitor sees the seven windows, each with two tiers, containing 64 lights, comprising 264 panels and 113 tracery lights. The upper tier depicts saints, while the lower tier depicts prophets carrying messianic texts. A keen eye can even spot Adam with a spade and Eve with her distaff and spindle.

On either side of the entrance to the choir (the chapel is in the shape of a T, with the ante-chapel at right angles to the chapel) two windows contained four depictions of the Crucifixion, with the Apostles above.

Altars for masses were placed below the windows and today there is still an altar beneath the south east window of the ante-chapel. Across the base of the windows are inscriptions requesting prayers for Archbishop William of Wykeham, fundatore istius collegii' - founder of this college.

The prophets and saints stand in niches, above them canopies and at their feet pedestals, surrounded by elaborate detail and much colour. As Philip Opher has pointed out in his pamphlet on Oxford stained glass, the figures overlap their frames, giving an almost contemporary three-dimensional quality.

They are full of character: the women beguilingly modest, the men bold and possibly rash. The faces are detailed and many an elaborate hairstyle is on display. There's no doubt the figures have presence and power.

The range of colours too is far richer and wider than, say, the stained glass at Merton College a century before. Cloaks and robes are glorious purple, lime green and differing shades of red, with plenty of white glass to allow for the fashion of a bright interior. The glass itself gives an overwhelming jewelled effect'.

The windows are also important because of their association with William of Wykeham, and tell us much about the devotional preoccupations of this scholarly, ecclestiastical politician through his choice of saints and prophets portrayed.

Like any ancient institution, over the years New College and its chapel have had their share of problems and changes. The Protestant Reformation, with its hatred of idolatry, saw the destruction of much glass.

By contrast, the 18th century - though otherwise a period of distressing somnolency' in the University's history - witnessed much activity in the chapel, the choir in particular undergoing many changes. The usual 19th century whirlwind of change swept into New College as in so many other places, while the glass was taken out entirely in the Second World War.

Stained glass has always needed restoration after a certain period of time. That time came most recently in the 1980s, when the college contacted the York Glaziers' Trust. The Trust, founded in 1967, is responsible for the preservation and conservation of the stained glass window of York Minster, which houses one of England's largest single collections of medieval glass. In the aftermath of the 1984 fire at the Minster, the Trust was heavily involved in repair work.

It also provides a comprehensive service for the conservation and restoration of stained glass throughout the United Kingdom and has worked with Oxford colleges, as well as museums and churches.

So when the restoration of the stained glass windows in the ante-chapel became one of the objectives of the New College Sixth Century appeal back in the 1980s, the trust was called in to report on the state of the glass.

It found much of the glass pitted and corroded, especially on the outside while work carried out at the end of the 19th century had also been destructive.

Some of the glass had been badly broken, often into postage stamp-sized pieces, while other bits were long lost and had been replaced over the centuries with glass from other parts of the chapel.

Sometimes this approach was restrained, with a missing head replaced by plain glass. Sometimes not. And inevitably, some of the colours had faded, particularly the yellows. But the conclusion of the report was that improvements could be made.

The main objective of the process has been to restore, as far as possible the transparency of the glass by the removal of accumulated soiling and to improve the legibility of figures.

And so the 20-year restoration began, with window panels taken out in turn, starting from the north-east corner and working anti-clockwise. In all, seven complete windows have been restored and each on average was away for a year in York.

The conservation of the stained glass of each tier takes some 3,000 man hours. Panels were photographed and documented (everything must be reversible for future generations that may not like the present restoration) and rubbed with black wax to record where the leads were, so track could be kept of all pieces before dismantling.

The glass was then cleaned under microscope using a gentle fibrous cleaning agent and Ph-balanced water. Cracked and fragmented pieces were re-bonded and missing pieces replaced.

Inevitably there were difficult decisions to make. For example, should alien' glass from a later period remain? And if not, there must be a good reason to omit it.

Then glass for any new areas was cut and painted, following the style of Thomas Glazier, and reglazed to the original lead lines.

All this - unlike much previous restoration - was fully documented. Finally the panels were put back with external glazing in an isothermal system, protecting the windows from the weather and holding them in a stable environment - not unlike double glazing, and allowing the glass to breathe.

In all this, there has been a close working relationship between glazier and New College (particularly Michael Burden and the clerk of works), with advice taken from historians and scientists. But once decisions were taken, it was too late to change segments of glass that were in the wrong window!

One pleasing by-product has been a new window for the vestry, created by Rachel Thomas in York. Her Tree of Life window incorporates both modern glass and fragments of the medieval glass removed from the ante-chapel windows during restoration.

The design earned Rachel the 2006 prize for work of outstanding individual craftsmanship from the York Guild.

The tree is made up of glass in subdued but delicate colours, much of it green-tinted with silver stain. It fits into the vestry beautifully.

Rachel is now designing a second window for the chapel's sung' room. As she says, it's a very exciting commission as it's so rare to work with old glass.

Meanwhile as the ante-chapel windows glow in their restored glory, New College is setting out on the restoration of the windows in the main body of the chapel, another 20-year project. William of Wykeham and Thomas Glazier would surely be pleased and grateful indeed.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article