CATRINA Loman remembers the day the Nazis came for her father.

He was in the garden chopping wood. The professor looked at the soldiers. The soldiers stared back.

Catrina, then little more than a toddler, now an 84-year-old woman with children and grandchildren of her own, did not see her father for another 24 months.

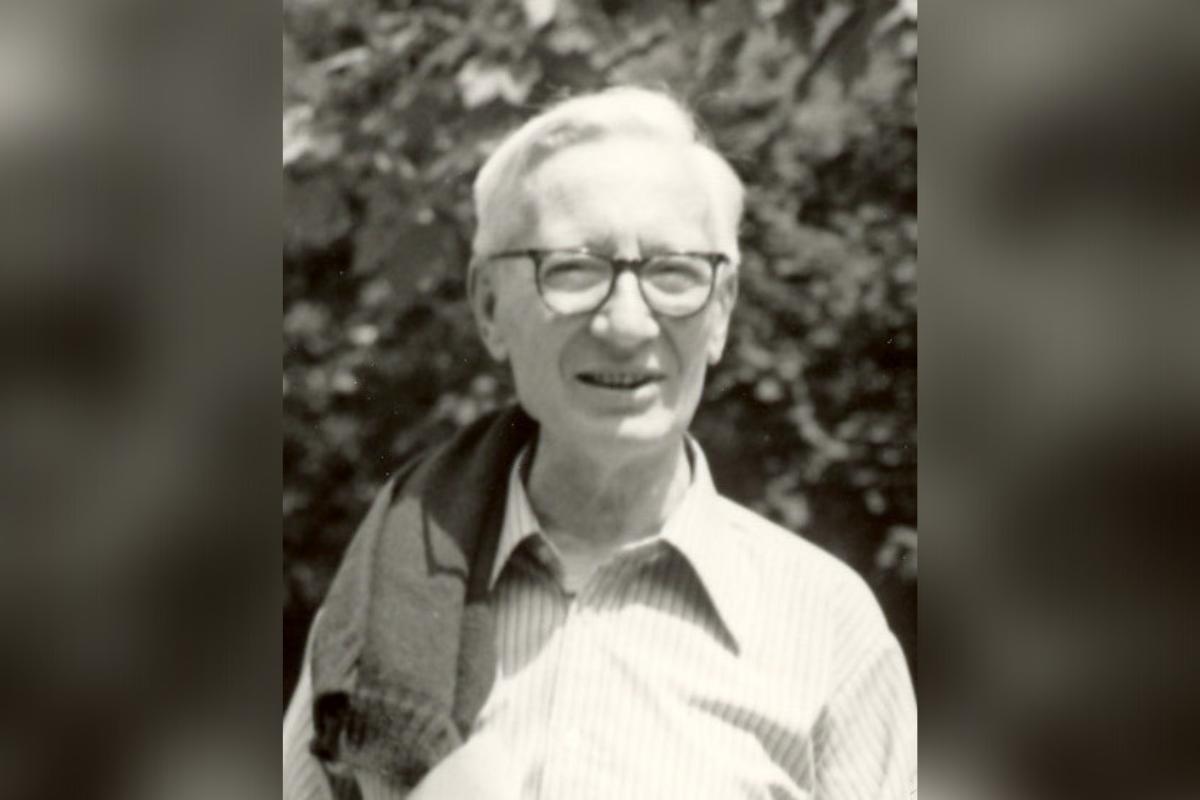

Professor Niko Tinbergen spent the next two years in a Nazi detention camp. He came to Oxford in 1949, by then already a noted biologist specialising in animal behaviour and a professor at the University of Leiden, and went on to count a Nobel Prize among his awards.

Mrs Loman was among the family members who returned to Summertown this month to see a new blue plaque unveiled on the Lonsdale Road house where Prof Tinbergen and wife Elisabeth made their home.

“I remember the invasion in 1940,” she said.

“I was two-and-a-half. I remember the planes coming over Leiden, where we were living, and our mother telling us three kids to sit on the stairs, which were against the wall and which were know as the safest place to sit.

“I remember the planes coming overhead and being terrified.”

In October 1940, academics and staff at Leiden university received a letter from the authorities asking whether or not they were Jewish. A month later, the university’s Jewish staff were dismissed.

Students at the Dutch institution went on strike, encouraged by some of the teaching staff. Prof Tinbergen was one of a number of academics to speak out against the removal of their Jewish colleagues.

In 1942, by then living with his family in a countryside cottage home to 12 people in total, the Nazi’s came for Mrs Loman’s father.

She said: “It’s such a clear memory in my mind.

“I was four – almost five – and I remember standing in the back garden. My father was chopping wood.

“I could sense the atmosphere. It was very, very tense.

“Of course, I didn’t know at the time they were coming to take him away, but I remember the atmosphere very clearly.”

He was taken to Sint-Michielsgestel, a hostage camp in the south of the country.

There were aspects of the two years that were ‘almost like a sabbatical’; he was surrounded by politicians, academics and businessmen.

But the internees lived in a state of constant fear of being shot.

Mrs Loman said: “You knew any day you could be killed and in my father’s case you could be chosen from a group of people and killed in retaliation for a German who had been killed by the Dutch [resistance].”

After the war, he returned to the University of Leiden. The authorities created a new chair for him in experimental biology and there was reportedly anger among his colleagues when he moved to Oxford in 1949 to take up a fellowship at Merton College. Oxford did not make him a professor until the 1960s.

His daughter, who was 12 when the family moved to England, said it was ‘exciting’ for her and her siblings. “We were going to a new place and learn a new language.”

The family initially lived in Banbury Road and moved to Lonsdale Road in 1956. He was in the detached property until his death in 1988.

He was one of the modern pioneers of ethology, the biological study of animal behaviour. While at Leiden he experimented on the behaviour of stickleback fish and hand-reared birds like turkeys. At Oxford, he set graduate students to work on comparative studies of seabirds.

Prof Tinbergen’s books, including 1953’s The Herring Gull’s World and Animal Behaviour published in 1965, helped popularise his studies – as did a film, Signals for Survival, he made for the BBC in the late 1960s.

Elected a fellow of the Royal Society, he received the Nobel Prize in physiology in 1973.

Prof Marian Stamp-Dawkins, who unveiled the blue plaque to her former supervisor this month, was one of his graduate students.

“I came here to Oxford because I read one of his books,” she told this newspaper.

“He was really inspiring. He gave you his absolute, full attention when you were there. He was quite light-touch in that he encouraged us to do our own thing.”

Prof Stamp-Dawkins, who occupies the same professorship in ethology as her former tutor, recalled how he would sit on an ‘orange box’ during their meetings and roll his own cigarettes. “He was always dressed in field gear. He never lectured or gave tutorials in a gown or tie.”

Unveiling the plaque last week, she told an assembled crowd of Prof Tinbergen’s family, former students and university dignitaries: “A lot of biology stands on the shoulders of giants and one of those giants was Niko Tinbergen.”

The professor’s daughter, Gerry Carleston, 72, was delighted – but, perhaps, a little bemused. “They belong to other famous people,” she said of the blue plaques, which mark the former residences of notable people nationwide. “People like Dickens or Churchill – not father!”

Read more from this author

This story was written by Tom Seaward. He joined the team in 2021 as Oxfordshire's court and crime reporter.

To get in touch with him email: Tom.Seaward@newsquest.co.uk

Follow him on Twitter: @t_seaward

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel