Hugh Williamson remembers how his father Tony Williamson fought racism in the 1960s

Sorting through my father’s papers at his home near Oxford, I come across cuttings from the Oxford Mail that give me a jolt.

They are about events in the city decades ago, in the 1960s. Yet there are such strong parallels to today.

Recently, there have been protests in the city streets against the statue of Victorian imperialist Cecil Rhodes outside Oriel College. Hundreds marched down High Street and sat outside the college entrance, a building funded a century ago by Rhodes. “Rhodes Must Fall” is the protesters’ battle cry.

There are parallels in Oxford in early 1962. The Conservative Government under Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had tabled the Commonwealth Immigration Bill, to heavily limit immigration from the former colonies in the Commonwealth.

The Tories said it was necessary to protect jobs of British people. Labour called the draft “cruel and brutal anti-colour legislation”.

People from many walks of life in Oxford opposed the Bill. Tens of thousands of people from the Commonwealth had settled in Oxford, filling labour shortages in industry and the public sector, giving the city a multicultural identity earlier than other places. Pressure groups were

emerging to promote racial integration and anti-racism.

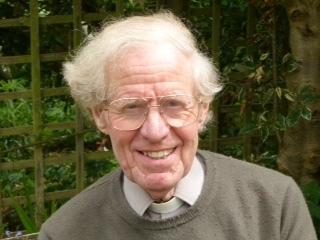

Tony Williamson in 1960 Picture: Hugh Williamson

Canon Tony Williamson, my father, was part of this movement. He was a freshly elected Labour member of Oxford City Council, giving him a voice, a platform, to speak out.

On Sunday, February 4 1962, those opposing the Bill marched through the city centre under the Movement for Colonial Freedom banner, ending outside St John’s College in St Giles.

Read more: A look back at protests in Oxford

My father spoke to the crowd. As the Oxford Mail reported: “Mr Williamson, waving a copy of the Bill, told an audience of about 200 people: ‘We have got to see that we get over this problem without making coloured people scapegoats. We cannot build our council houses in Oxford because we have not got enough labour. We have 3,000 jobs waiting and yet we say ‘No, you cannot come in’”.

Despite this protest, and others across the country, this battle was lost – the Bill became law in July that year. Race relations didn’t disappear from the political agenda, however.

Conflicts over race and racism continued. In one case, an Indian man, Hans Raj Gupta, who worked on the Oxford buses, was the victim of a racist attack outside his home, only months after he had been recognised as the first Indian bus inspector in Oxford.

Dozens of anti-racism protesters were arrested for occupying Annette’s hair salon in Cowley Road, after staff refused to cut the hair of black and Asian customers.

Dozens more were detained when Enoch Powell, the far-right politician, came to speak at Oxford Town Hall.

Read more: Oxford city centre parking will cost £6 an hour

The offices of the Oxford Committee for Racial Integration (OCRI), a pioneering anti-racist community organisation set up in 1965, were vandalised. OCRI warned of the rise of the “extreme right”.

My father was chair of OCRI for two years in the late 1960s. Indeed, this was the time in his career when he was most focused on anti-racism work.

One more example from his files. In 1965 – according to the Oxford Mail, he played a big part in overturning an evidently racist decision by Oxford police that stirred such a controversy that it reached the Home Office and House of Commons.

Immigration officers blocked Ghulam Shabir, a 15-year-old Pakistani boy from entering the UK to join family members in Oxford, based on a local police report that the family was living in overcrowded conditions.

My father was shocked by the immigration decision, called Oxford police and council officials and compiled facts on the case – leading to an abrupt police climbdown, admitting their original report was untrue.

Read more: What you said: we shouldn't be ashamed to fly Union flag

“A dogged tracking back of the facts by Councillor the Rev A W Williamson”, as the Oxford Mail noted, forced a retreat by the Home Office and a decision to allow Ghulam to re-apply for an entry permit to the UK.

Recently, I visited the Oxford sites of the current and historic struggles against racism. It was quiet outside Oriel and St John’s. A few tourists, but no protesters that day. As I stood outside St John’s, I wondered about my father’s mood as he prepared to speak to the crowds on that Sunday afternoon. Was he nervous?

He was, after all, only 28 at the time and had been a councillor for only nine months.

Tony Williamson

He told me racism was a problem in the car factory where he worked – from managers and workers towards black and Asian colleagues.

Read again: Young Oxfordshire boxers take on top rivals

Maybe, it was also a problem in Cowley, the largely working-class district where he lived with my mother and sister. Did this motivate him to speak out? Or did he sense the growing significance of questions of race in society, in the years, the decades to come?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel