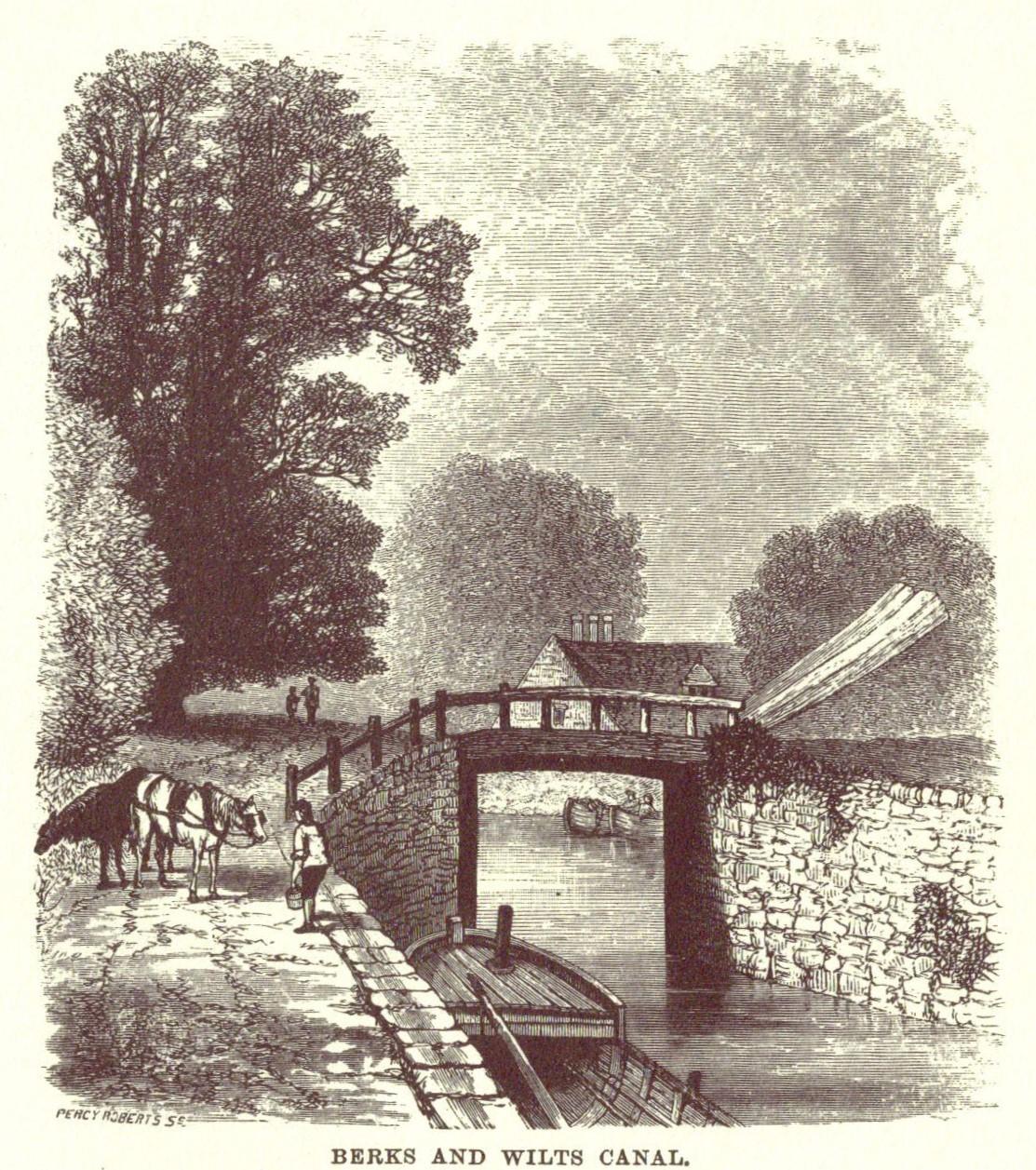

The Wilts and Berks Canal was first promoted at a meeting in Swindon in 1793 at the height of canal mania.

It was seen as a way of providing cheap transportation of goods between the Vale of the White Horse and north Wiltshire to the Bristol and London markets. It eventually became a link in a chain of canals covering the West Country and the Midlands.

The Bill promoting the canal received Royal Assent in 1795 but fifteen years elapsed before the canal reached the Thames at Abingdon. The report in Jackson’s Oxford Journal on the 22nd September 1810 relates how the company’s boat carrying the proprietors passed through the last lock into the Thames at 2.30pm to a musical accompaniment and the cheers of the assembled crowd. A celebration dinner followed in the Council Chamber attended by local MPs and ‘a numerous assemblage of gentlemen’. Prominent local solicitor Benjamin Morland, one of the proprietors, reported in December that 100 boats had travelled up and down the canal in the first five weeks. The Oxford Canal Company, with offices in Abingdon, was alarmed by the potential damage to its trading position.

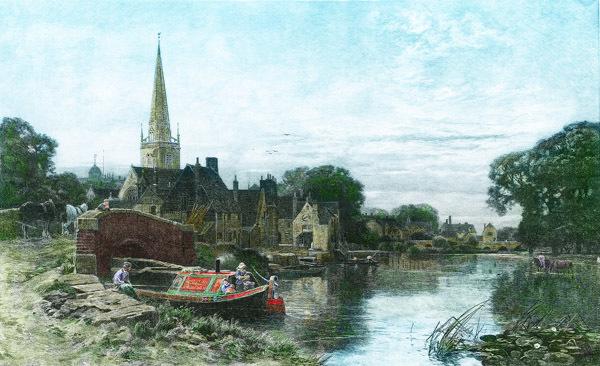

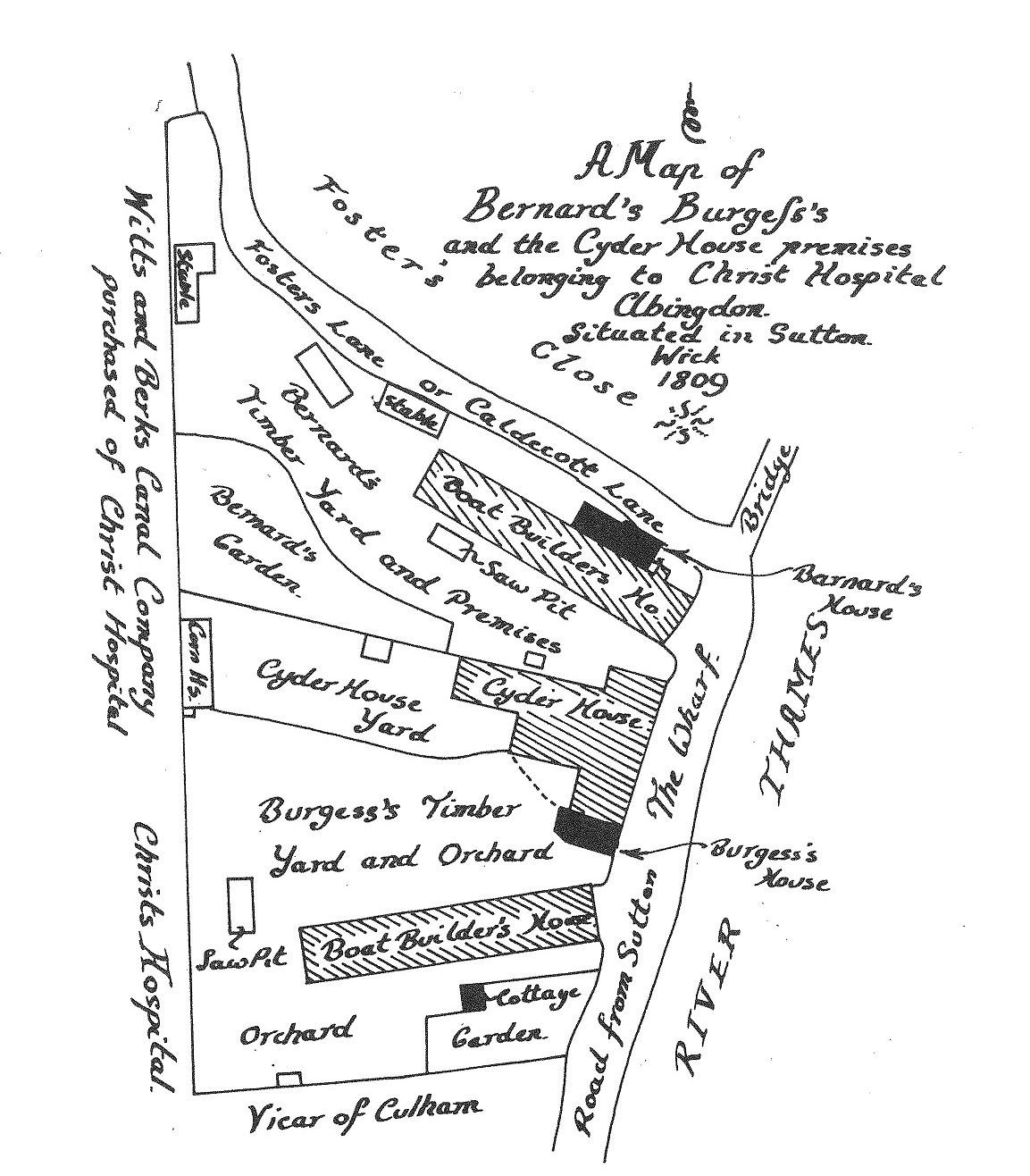

A wharf had been in existence on the riverbank since the 17th century, created by local charity Christ’s Hospital who owned the right of passage over St Helen’s Wharf at that time, though this is no longer the case. The confluence of the Thames and the Ock was spanned by the medieval St Helen’s Bridge, a pack horse bridge which connected Abingdon to the old road to Sutton Courtenay. The riverbank here, now known as the Margaret Brown Memorial Garden, was occupied by established boatbuilders and a cider house. Despite some disquiet that the canal could affect the water level in the river Ock and ultimately St Helen’s Mill, land adjoining this area was sold to the canal company for a lock, basin and access to the Thames. Specified in the 1795 Act was the replacement of St Helen’s Bridge, but this did not happen until 1824 when the canal company installed the cast iron bridge bearing the inscription “Erected by the Wilts and Berks Canal Co. AD 1824. Cast at Acramans Bristol”. Two inscribed stones are set into the retaining walls bearing the Inscriptions ‘ST HELEN’S WHARF ‘and ‘W & B WHARF’.

During its first thirty years of operation there was a steady increase in revenue from tolls. An advertisement in the local press shows that Abingdon evolved as a major centre in the waterway network, transporting and forwarding goods, eg pottery from the Midlands, to Bath and Bristol and vice versa. In 1837 over 10,000 tons of coal were handled at the company’s wharf in Abingdon, the busiest coal wharf at that time. There were problems with water supply and the canal was unable to compete with the Kennet and Avon Canal on the lucrative Bristol to London trade route. It had also been designed for narrow boats seventy-foot long rather than larger barges. The final blow to its success was the GWR’s decision to build its London to Bristol line closely following the route of the canal. The final irony was the use of the Wilts & Berks to transport the bricks used in the line’s construction. The canal was finally abandoned in 1914.

What traces remain? On Wilsham Road stands Wharf House, the former manager’s house, and the old stone wall of the last lock into the Thames. The canal ran parallel to the line of trees on Caldecott Road where there was a small lifting bridge almost opposite the entrance to Caldecott House. Using old and modern OS maps the route of the canal may be traced west of Drayton Road, weaving through the Ladygrove estate. Walking along Mill Road towards New Cut Mill, formerly known as Bugg’s Mill, the line of the canal can be deduced from the twin hedgerows. This part of the disused canal was incorporated into the Second World War GHQ Red Stop Line as defence against invasion.

In 1997 the Wilts and Berks Canal Trust was formed to protect the surviving disused canal and restore the original route where feasible. In Abingdon much of the route is built over but in 2006 a small stretch, called Jubilee Junction, was dug to connect with the Thames downstream of Abingdon Marina and hopefully will eventually be linked to the route west of the town. Future reconstruction depends on long term plans for the area, notably the possible construction of a new reservoir.

Readers may be interested in the AAAHS December Zoom lecture by Martin Buckland on ‘Canal People’. Email chair@aaahs.org.uk for further details.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel