The eating habits of the Romans as revealed in the excavations at Pompeii is the subject of the fabulous exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum, Last Supper at Pompeii, which I urge everyone to see during the months (till January 12) it still has to run.

Looking around a couple of weeks back, I was conscious of tales concerning food and drink that I had been obliged to omit, through pressure on space, from my recent articles on Iris Murdoch, the 9th Duke and Duchess of Marlborough, and the journalist and wine writer Auberon Waugh. Permit me to serve them up today.

Approaching them in order of precedence, I begin with the former Consuelo Vanderbilt’s description of dinner à deux with her duke at Blenheim Palace, which at the time of her ‘accession’, in 1895, contained only one bathroom.

Consuelo made use of it (or possibly a tub in her room) before dressing for these dreaded meals that loomed “ominous and wearisome” – as she wrote in her autobiography – at the end of a long day of palace business.

“They were served with all the accustomed ceremony, but once a course had been passed the servants retired to the hall; the door was closed and only a ring of the bell placed before Marlborough summoned them.

“He had a way of piling food on his pate; the next move was to push the plate away, together with knives, forks, spoons and glasses – all this in considered gestures which took a long time; then he backed his chair away from the table, crossed one leg over the other and endlessly twirled the ring on his little finger . . .

“After a quarter of an hour he would suddenly return to earth . . . and begin to eat very slowly, usually complaining that the food was cold! As a rule neither of us spoke a word.”

Contrast the leisurely horror of this with the high-speed service at one of the grand dinners with guests, organised by the duchess, at which eight courses were served in one hour flat.

“This was not an easy matter,” she wrote, “since the kitchen was at least 300 yards from the dining room.”

Quick-fire dining was the fashion at the time in Consuelo’s native New York where the Vanderbilts’ friend Mrs Stuyvesant Fish limited a multi-course dinner to a strict 50 minutes, with the servants ordered to remove plates whether guests had finished or not.

And if 50 minutes seemed rather a long time to wait for a cigarette, there was no worry on this score. Mamie Fish permitted smoking with the soup. Princess Margaret would have approved.

A great woman was Mrs Fish. She was once told by a rival hostess: “And this is my Louis Quinze salon.” “Oh,” said Mamie. “And what makes you think so?”

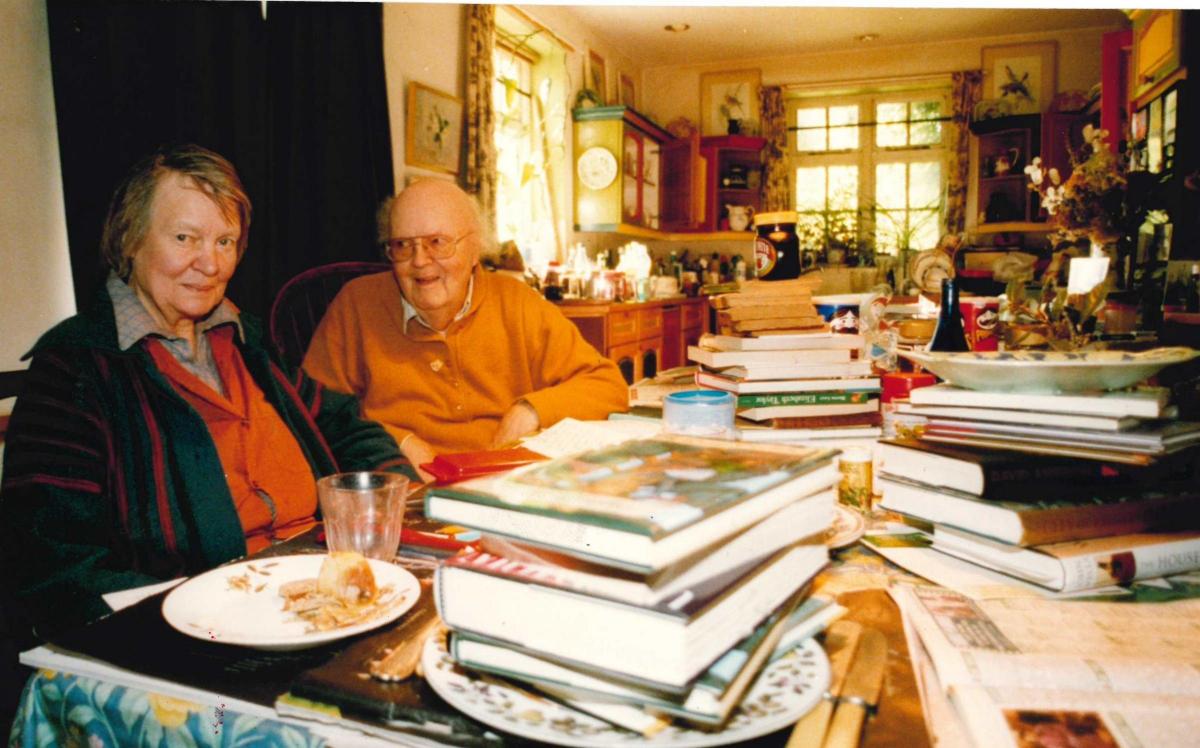

From the exacting requirements of high society we move to a far less salubrious milieu for dinner with the novelist Iris Murdoch and her English professor husband John Bayley, as described by their friend A.N. Wilson in his book Iris Murdoch As I Knew Her.

This was not in their famously filthy Oxford home, in Charlbury Road, but in their equally disgusting London flat with “the loo not merely stained but encrusted, a bas-relief of limescale, ancient excrement and some not so ancient”.

The ‘meal’ for four – fully deserving of those inverted commas – began with a small pork pie cut into segments. This comestible was all present and correct, unlike the pie in Charlbury Road whose disappearance into the domestic clutter (see above) post-purchase, never to be seen again, led the Bayleys to refer henceforward to any missing object as having “gone to pork pie land”.

There followed salami, “which had known better days”, whiskery olives and scrambled eggs. “Only one egg unfortunately,” said Bailey. He called the dish “t-t-t-tapas”.

Finally, there were cheese and biscuits and Mr Kipling cakes, exceedingly good, we hope.

Of booze, there was certainly no shortage, Wilson states – “gin and vermouth, two sorts of white wine and a mélange of reds”.

That mélange would not have appealed to the novelist Evelyn Waugh had one of its constituents been claret. According to his son Auberon, writing in Waugh on Wine (Quartet Books, £10), he abruptly ceased drinking red Bordeaux in 1956 – sold every bottle in his cellar and sedulously avoided it for the last ten years of his life.

Bron believed the reason for this was tied up with the ‘U/non-U’ debate that so exercised Brits in the 1950s after the publication of Nancy Mitford’s Noblesse Oblige.

In his contribution to the book, Christopher Sykes wrote of “a Gloucestershire landowner who believes that persons of family always refer to the wines of Bordeaux as ‘clart’, to rhyme with ‘cart’, a delusion showing ‘an impulse towards gentility’”.

That person was Sykes’s pal Evelyn who quickly decided change was necessary. The Gloucestershire house went, and so did the ‘clart’, never to be mentioned again.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel