While ‘Faithful though unfortunate’ has ever been the family motto of the Dukes of Marlborough – it is rendered on their coat of arms in Spanish (‘Fiel Pero Desdichado’), though no one knows why – the words seem singularly inappropriate when applied to the ninth holder of this august title.

Fidelity was certainly not the way with Charles Richard John Spencer-Churchill, nor yet with his first American wife, the former Consuelo Vanderbilt. Each cheated on the other early in their marriage and carried on doing so.

And who could be called ‘unfortunate’ – or ‘disinherited’ or ‘unblessed’, as ‘desdichado’ can also be translated – when that person has received a sum not unadjacent to £50m?

That (in its modern equivalent) is what was handed over to the duke in railway shares by Consuelo’s father, William K. Vanderbilt, one of the world’s richest men – his father had been the very richest – as his daughter’s dowry.

It was a straightforward business deal, supplying a financial lifeline to the duke and and his cash-strapped Blenheim estate, while bestowing the title of duchess, with a palace over which to rule, on the lovely 18-year-old Consuelo.

This gave status greatly to the delight of her socially ambitious mother, Alva Vanderbilt (if not entirely to the young woman herself who, like her husband, was in love with someone else when they married).

Yes, Consuelo was the sort of bride immortalised by the great American writer Edith Wharton as one of The Buccaneers, in the title of her last (and uncompleted) novel.

Another was her friend Mary Goelet, who was to become the wife of the Duke of Roxburghe, a cousin of the inaptly named ‘Sunny’ Marlborough – his disposition, especially in the presence of his wife, being anything but.

The name, of course, derives not from the duke’s demeanour but from the courtesy title, The Earl of Sunderland, which he carried from his birth.

The father of the present duke was also called Sunny, a fact not understood by the oafish politico Woodrow Wyatt – the father of Boris Johnson’s one-time squeeze Petronella Wyatt – who referred to him in his journals as ‘Sonny’.

The story of the 9th duke’s unhappy marriage (actually marriages, there being another, equally doomed, to a second American, Gladys Deacon) has not gone unrecorded.

It was told by Consuelo herself in her beautifully written 1953 autobiography, The Glitter & the Gold, and more recently (2005) by my one-time Osney neighbour Amanda Mackenzie Stuart in Consuelo and Alva.

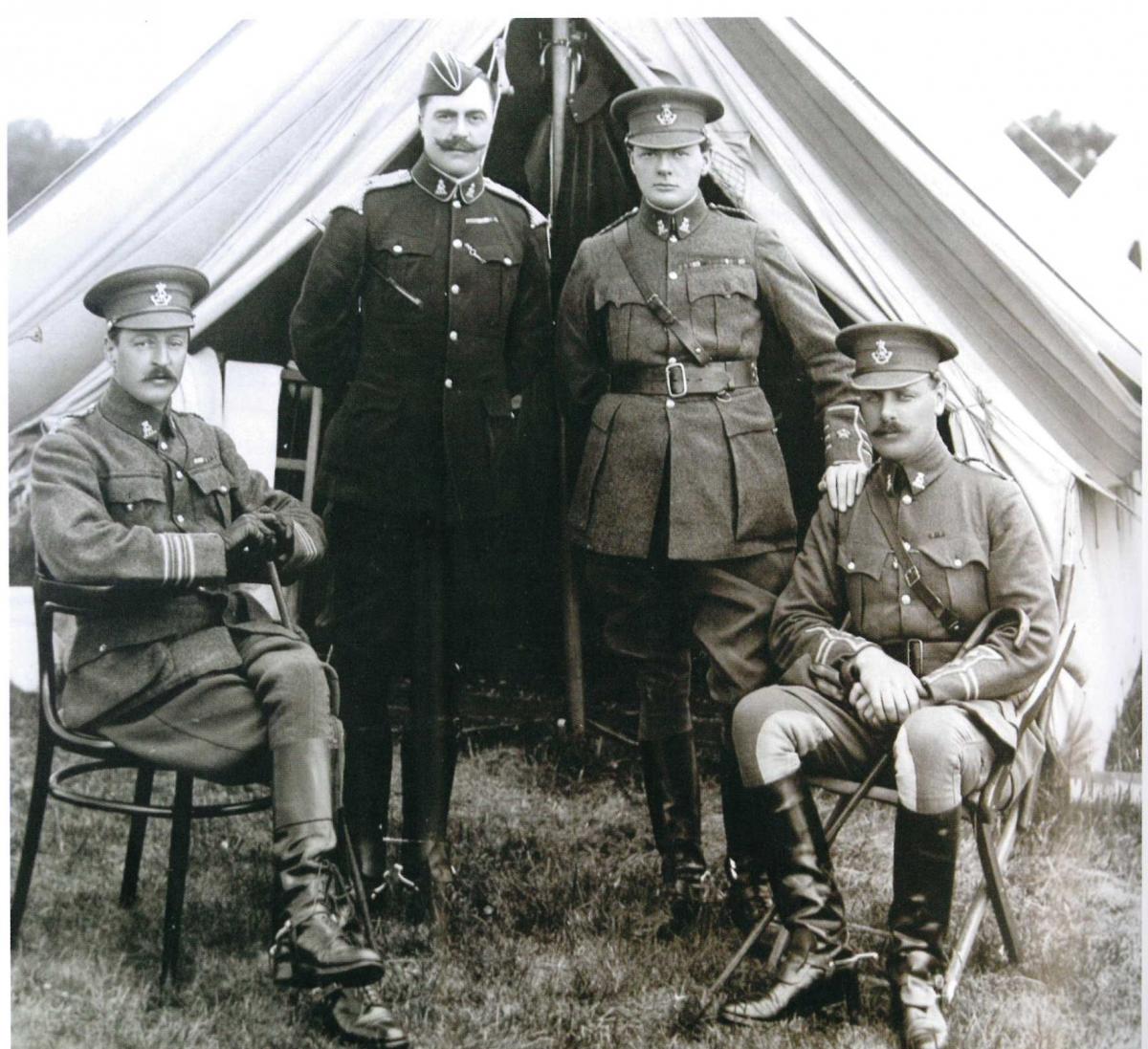

Now we can read it again – and of so much more besides, especially of his great friendship with his cousin Winston Churchill – in an exceptionally handsome new book, The Churchill Who Saved Blenheim, The Life of Sunny, 9th Duke of Marlborough (Unicorn, £25).

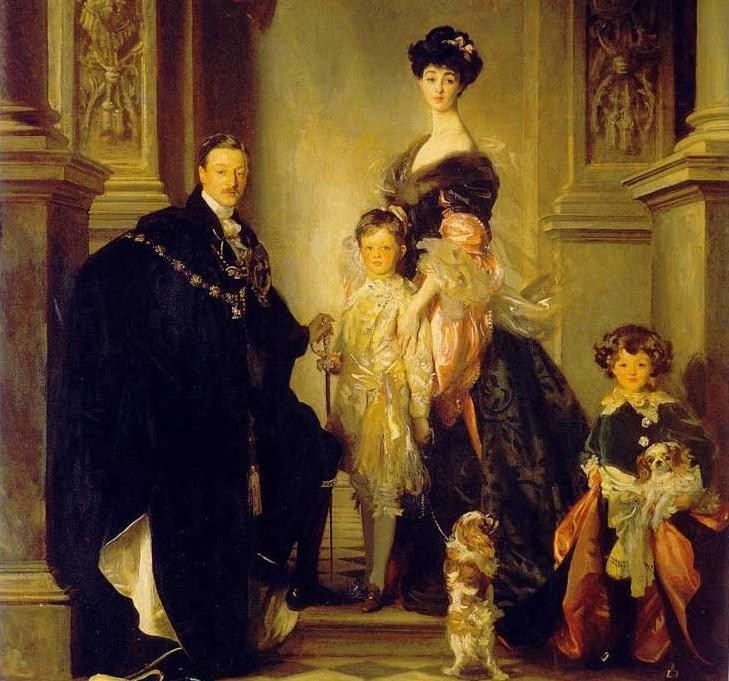

The scrupulously researched (and beautifully illustrated) volume is a joint work by one of the duke’s grandsons, Michael Waterhouse, who has previously published a life of the Liberal statesman Sir Edward Grey, and Karen Wiseman, the former head of education at Blenheim Palace.

It comes with a hearty endorsement from Hugo Vickers, the biographer of the aforementioned Gladys Deacon. He says the book at last does justice to a figure “wickedly traduced” by Consuelo in her autobiography.

I think, in fact, that might be laying it on a bit thick. Before me is a copy of The Glitter & the Gold, on the back cover of which is stated, fairly: “Sunny Marlborough had also made sacrifices. He, too, had been deeply in love with someone else. It followed that after the provision of the customary ‘heir and the spare’ [an expression, incidentally, that Consuelo is believed to have initiated] separation became inevitable.”

Where Vickers is right, though, is in stating that The Churchill Who Saved Blenheim begins with “a devastating pistol shot”.

This comes in a prologue in which is printed a letter sent by the duke to the lawyer (and Lord Chancellor-to-be) Richard Burdon Haldane, from whom he sought advice concerning Consuelo’s infidelities.

These involved not only her American lover, Winthrop Rutherford, but also the duke’s cousin Frederick Guest whom he surprised with his wife at his London home. “They both received me in a confused manner.”

This had led to conversation “in which she confessed to me that she had been on intimate relations . . . for a space of six weeks”.

He told Haldane: “I have tried during the last 18 months under circumstances and situations sometimes overwhelming in the sorrow and grief that they have brought me forcing me to bear the deepest feelings of misery, to sink entirely my own personal feelings and inclinations.”

It is hard not to pity him.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here