In the words of the immortal Vikki Carr and her 1967 hit: “It must be him.” But why is this necessarily so? Must the prime ministership of Boris Johnson be considered the climax to a political drama as inevitable as the bloodbath that closes a Greek tragedy?

I fear that it must, and the reason has everything to do with the shadowy, who-the-hell-are-they? status of the Tory leadership rivals who were ranged against him.

With the single exception of Michael Gove, the line-up of Boris’s opponents consisted largely of unknowns. I include in this his remaining ‘rival’ Jeremy Hunt , who is better remembered as ‘victim’ of a pronunciation blunder than for anything he has achieved as foreign secretary.

Contrast this, for instance, with the line-up of big-league names, familiar to all – Rab Butler, Reginald Maudling and the former Oxford MP Lord Hailsham (Quintin Hogg) – in the contest to succeed Harold Macmillan as PM in 1963. The mantle was bestowed – notoriously in those days of ‘the magic circle’ – on the 14th Earl of Home (Alec Douglas-Home).

Odd, isn’t it, that the Tories, in their newer democratic days, are about to deliver us another product of Eton College and Oxford University.

Mention of democracy obliges me to observe that it is hardly in the spirit of this that the nation should have forced upon it as prime minister a gentleman for whom none of us has voted (in the role) – someone about whom a majority would perhaps have uttered: “Anybody but.”

What has propelled the Tories towards a Boris canonisation is the certainty that his various dismal rivals would be even less favoured by the electorate.

Johnson, of course, has always enjoyed his high public profile, though this has been earned through his widely acknowledged status as a buffoon and unrepentant bad boy.

In representing him over the years as a cartoon character in Dennis the Menace mode, Private Eye – while seeming to attack him – has actually been doing him a good turn.

A rackety private life of a sort that would have once made him politically beyond the pale, these days seems almost an endearing feature of his character for the electorate. Yes, I include recent altercations with current squeeze Carrie Symonds. So like the rest of us . . .

I don’t imagine this would be the view, however, of his estranged wife Marina Wheeler, the mother of his four children, who was dumped in favour of the glamour puss.

Many of my readers, I feel sure, will have met barrister Marina – the daughter of broadcaster Charles Wheeler – during Boris’s days as MP for Henley. (He was successor, incidentally, to Michael Heseltine, a should-have-been Tory leader who must be aghast at what his party is about to do.)

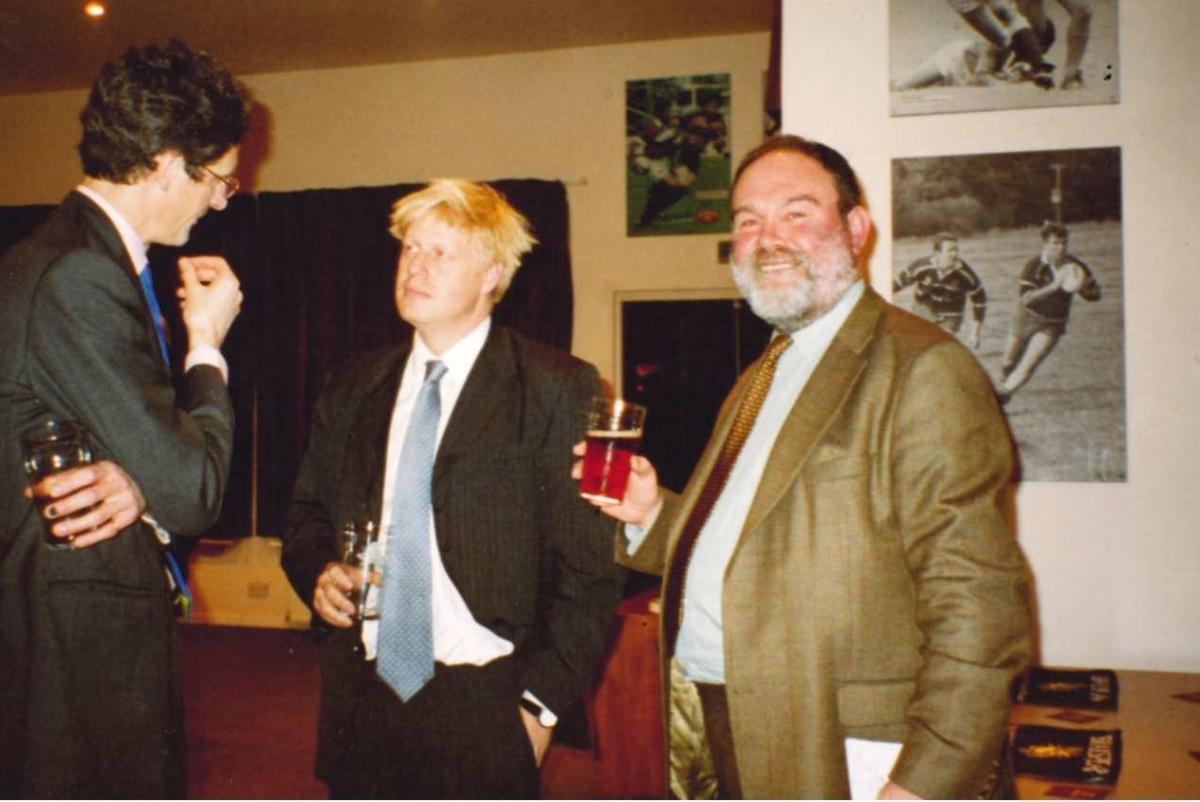

I met Marina, and was entirely charmed by her, at a party in the drawing room at Garsington Manor following a performance by Garsington Opera. Adopting his easily assumed ‘man of the people’ pose, Boris told me he was not especially fond of opera (affecting to know nothing of the Mozart work we had heard) and was there at the invitation of his godfather, the manor’s owner Leonard Ingrams, founder of the Garsington Festival.

A well-rehearsed aspect of Boris’s past, of course, is his fathering of a love child with journalist Petronella Wyatt, a colleague in his days as editor of The Spectator. As may be imagined the matter is extensively set out in his biography by another journalistic colleague, Sonia Purnell. Expect an updated edition any time soon.

Johnson’s solid career as a journalist is an aspect of his working life (like that of his hero Winston Churchill) that should not be overlooked. True, it got off to a shaky start after he was dismissed by The Times after allegedly making up a quote by the historian Colin Lucas (another of his godfathers).

Boris later made his name as a Brussels-bashing European correspondent with the Daily Telegraph and as its highly paid weekly columnist.

How highly paid was a matter of contention. When I passed comment in this column – citing a salary alleged elsewhere as £200,000 a year – Johnson took issue with me in the letters column. His criticism was leavened, to my pleasure, with his opening admission that “I always enjoy the works of Christopher Gray” and his closing observation that I was clearly not being paid enough for them.

Some years ago I met Boris’s journalist sister Rachel Johnson at the Sheldonian Theatre, where I was introducing her friend Robert Harris at the Oxford Literary Festival.

During the course of our conversation, I mentioned that I knew her brother. Sensing a name-drop, I suppose, she asked: “Which one? I have several,” a remark which sounded well rehearsed.

Will she still be saying that next month when Boris is – heaven help us – the prime minister?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here