The shelfful of supposedly comic writing stored at arm’s length from the loo in my bathroom is a sad reminder of the evanescence of journalistic fame, especially for practitioners striving to be funny.

In this graveyard of lost reputations there languish names like Alan Coren, Miles Kington and Michael Frayn, fading figures all and soon to be unknown to new generations of readers.

Basil Boothroyd anyone? He is totally forgotten now, along with the magazine Punch with which he was long associated. He is represented in my comedy collection with his 1967 book Let’s Stay Married.

From the same year comes the paperback All Ways on Sunday, by the Sunday Times columnist Patrick Campbell, which – having pulled it from the shelf – I discover not to be mine at all.

An act of petty larceny is revealed in the signature on the title page. This compendium of journalism by the stuttering star of TV’s Call My Bluff is the property of one ‘W. Littlejohn’. Had Bill Littlejohn pushed it the way of his son, my schoolmate Richard, and said: “You ought to try your hand at something like this, lad.”?

Perhaps. In any event Richard did take up the typewriter, becoming the star journalist of his generation, still in his pomp at the Daily Mail as I write (though I have heard talk of a possible defection).

A week or so back, I found myself discussing forgotten writers with the widow and son of the English humorist Auberon Waugh at a party in Daunt’s Bookshop in London. Lady Teresa Waugh, herself a novelist, and Alexander Waugh, the literary executor of his grandfather Evelyn, both cited James Thurber as a sad example.

It seemed impolitic in the circumstances to ponder how posterity is treating Bron Waugh. A little better than previously, perhaps, thanks to a book whose publication we were celebrating.

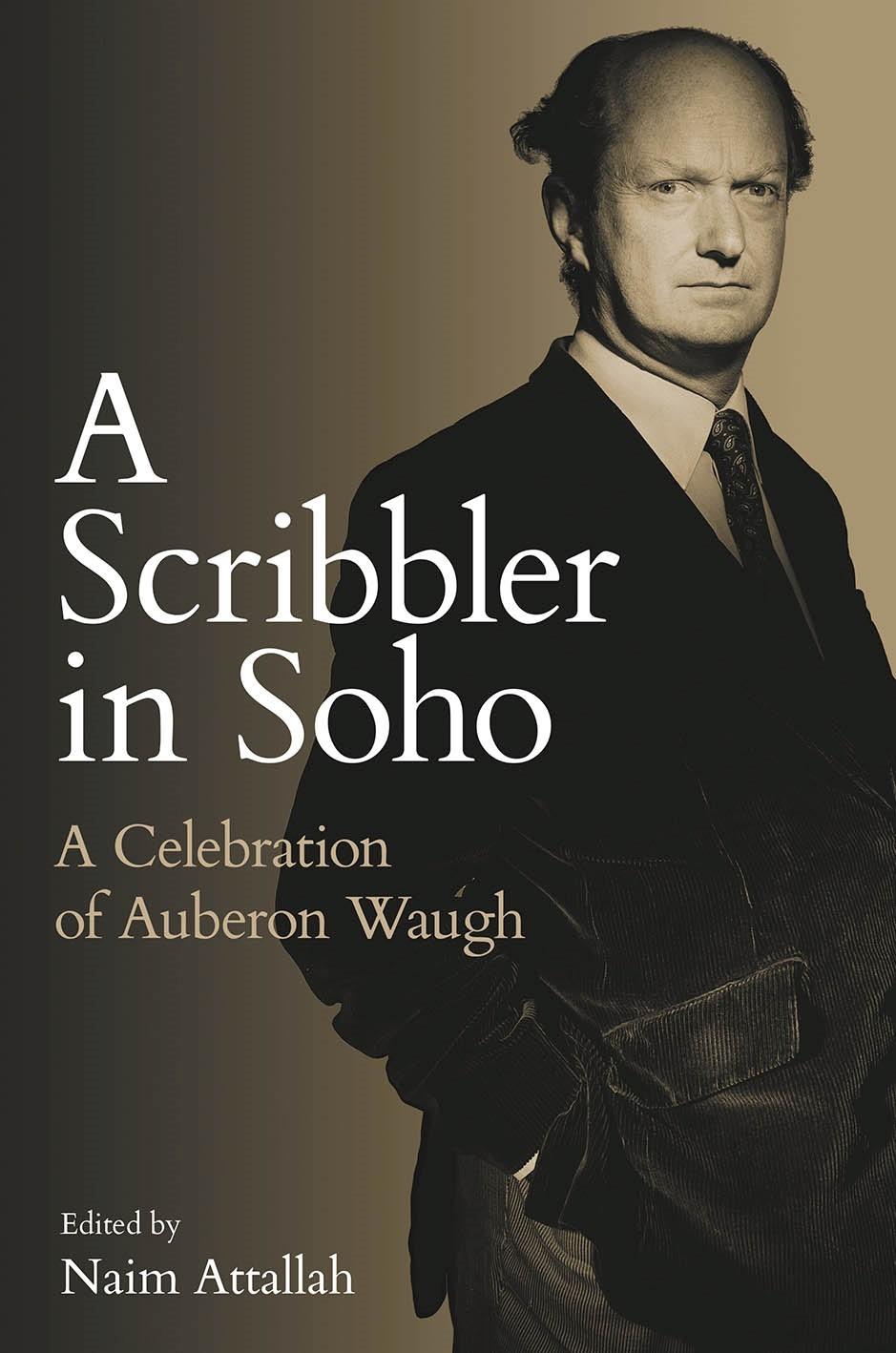

This is an entertaining collection of Waugh’s journalism, A Scribbler in Soho, edited with commentary by Naim Attallah and published, at £20, by Quartet Books, which he owns. Attallah was a long-time pal of Waugh and bankroller of The Literary Review which he edited from 1986 until his death in 2001.

The pair were partners, too, in the associated Academy Club, which occupied the basement of the magazine’s premises in Beak Street, Soho, later moving above the new offices in nearby Lexington Street

Operated in the eccentric way characteristic of Waugh, its six rules included one banning poets.

The reason for this was explained in one of Bron’s ‘Words from the Pulpit’ addresses delivered in each issue of the Literary Review during his editorship. A selection of these is featured in A Scribbler in Soho.

Bron explained: “The reason . . . was partly that they could talk about nothing but themselves, partly that they never paid for their drinks and partly that all the pretty women fell in love with them.”

Witty as these monthly sermons are, they are nothing in comparison with the hilarious, almost lunatic, style he brought to writing his diary in Private Eye between 1972 and 1985. He thought this his best work, and most readers would agree.

Its surreal style is well illustrated in a piece from August 1978 when he advises – following an outbreak of botulism among pensioners – that a change of diet is advisable.

“In Somerset, I always feed my OAPs on Kit-e-Kat. It keeps them sleek and frisky.”

When Margaret Thatcher became Tory leader in 1975, he opined: “I blame Denis Thatcher . . . for not keeping his wife under control. Anybody else whose wife [had ambitions to become prime minister] would shut her in her bedroom on bread and milk for a few days.”

In May 1977, he noted uses for nun’s urine (should you be lucky enough to have any) – as anti-freeze and silver polish.

In a brief speech at Daunt’s, Naim paid tribute to his friend.

He told us: “I miss him, especially when I see the mediocrity of today’s state of affairs and wonder what a field day Bron would have had describing [it] in his unique way.

“When I thought of publishing A Scribbler in Soho, part of my intention was to create a book which would allow a new generation of readers to discover just how funny and original Bron’s writings could be.”

I sincerely hope they do.

My hoard of Private Eyes is a treasure trove

HAVING read with huge enjoyment the marvellous pieces by Auberon Waugh assembled by Naim Attallah for the new book of his journalism, my appetite was whetted for more wit and wisdom from the sage of Combe Florey.

Happily, I didn’t have far to look, since tucked away in my loft are bagfuls of old copies of Private Eye covering the whole period (1972-1985) during which his diary appeared therein (and the years either side).

Plucking one at random – the edition for Friday December 26, 1975 – I found Bron on fine form as he surveyed a new list of Life Peers.

“Of the nine people named today, none is an obvious Soviet agent,” he wrote, “ none (so far as I know) has paid Wislon [sic – the Eye’s name for PM Harold Wilson] large sums of money, and none is a particularly close friend of Lady Forkbender.”

The last was a daring reference to Lady Falkender, the secretary and some said lover of Wilson. She was well known for resorting to lawyers concerning this allegation, and over the suggestion that she put forward the names for earlier honours on her notorious ‘lavender list’. Since Lady F. is now dead – as of this month – I can freely allude to both.

But it was things earlier in the magazine that caught my eye for their local interest.

Pseuds Corner featured appearances by Oxford-resident novelist Angela Huth and Oxford Dictionary editor Robert Burchfield.

I know/knew both; likewise Adam Carr, eldest son of the St Antony’s College Warden Raymond Carr, who featured in the Grovel gossip column concerning his profitable friendship with president’s daughter Caroline Kennedy.

The lead letter, fingering a journalist for plagiarism, came from Andrew Billen, of Essex. Could this be the Grandpont-resident interviewer of celebrities in The Times? Indeed, it could, he tells me, as a precocious 16-year-old.

He, too, possesses a hoard of Eyes, dating back to 1971. “What a strange lad I was.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here