IN 2002, Sarah Williams was given the devastating news by doctors that her baby had just a one per cent chance of survival after birth.

At 20 weeks, her unborn daughter had been diagnosed with thanatophoric dysplasia - an extreme form of dwarfism, where the skeleton doesn’t develop as it should in the womb.

Despite the overwhelming odds, however, the mother of two from Burford said there was never a doubt in her mind that she wouldn’t go through with the pregnancy.

The baby, Cerian, sadly died during birth from an unrelated complication.

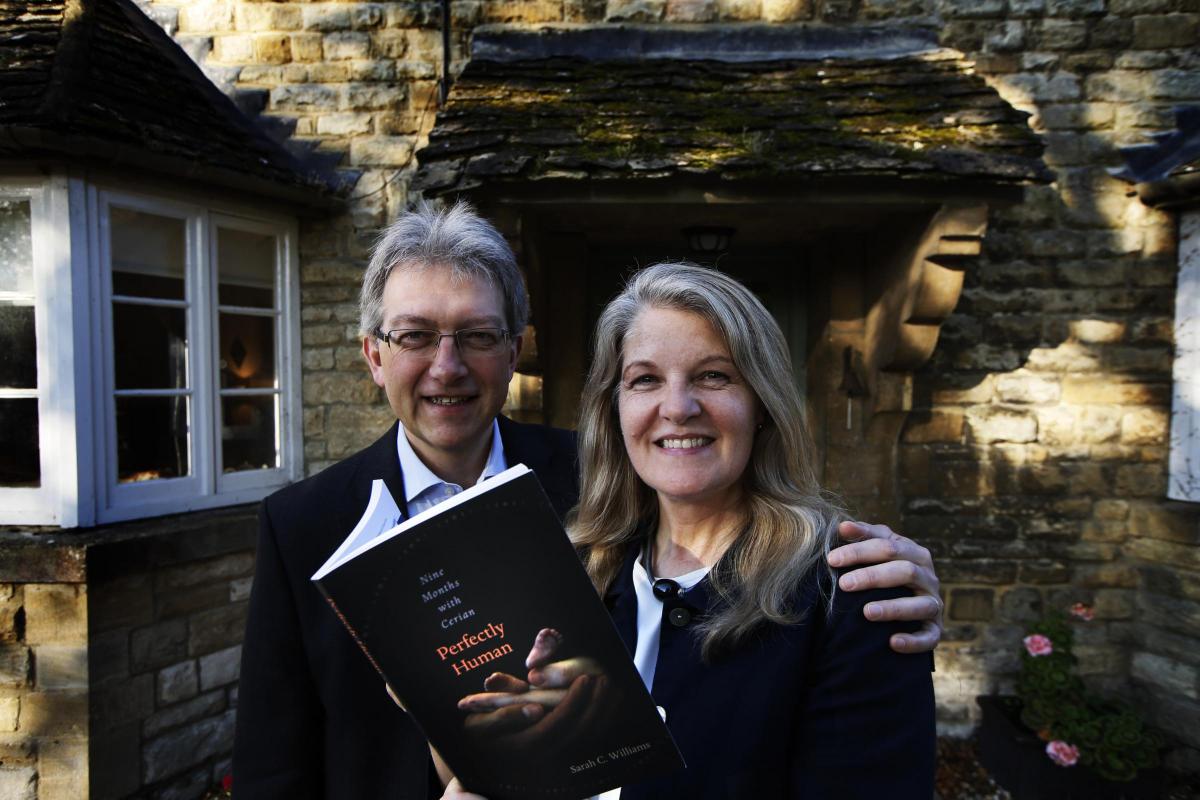

Both she and her husband Paul remain firm in the belief they made the right choice, however.

Speaking about the pain of losing her child Mrs Williams said: “It’s an ongoing grief, you don’t ever get over losing a child.

“She died of a placental abruption during the last stage of labour.

“That’s an important fact for me because my biggest worry was my baby would die in pain.

“She died like any other still birth, not because of her physical abnormalities.

“The doctors said she would either die during the birth or soon after the birth, but they weren’t clear on that.

“So we might have had an hour with her - even if we had had 10 minutes of our baby alive then we would’ve gone through with it.”

Mrs Williams revealed that the decision laid bare a lack of support for parents who choose to carry babies with potentially fatal abnormalities to full term, while also raising serious questions over the potential ethical issues related to prenatal screening.

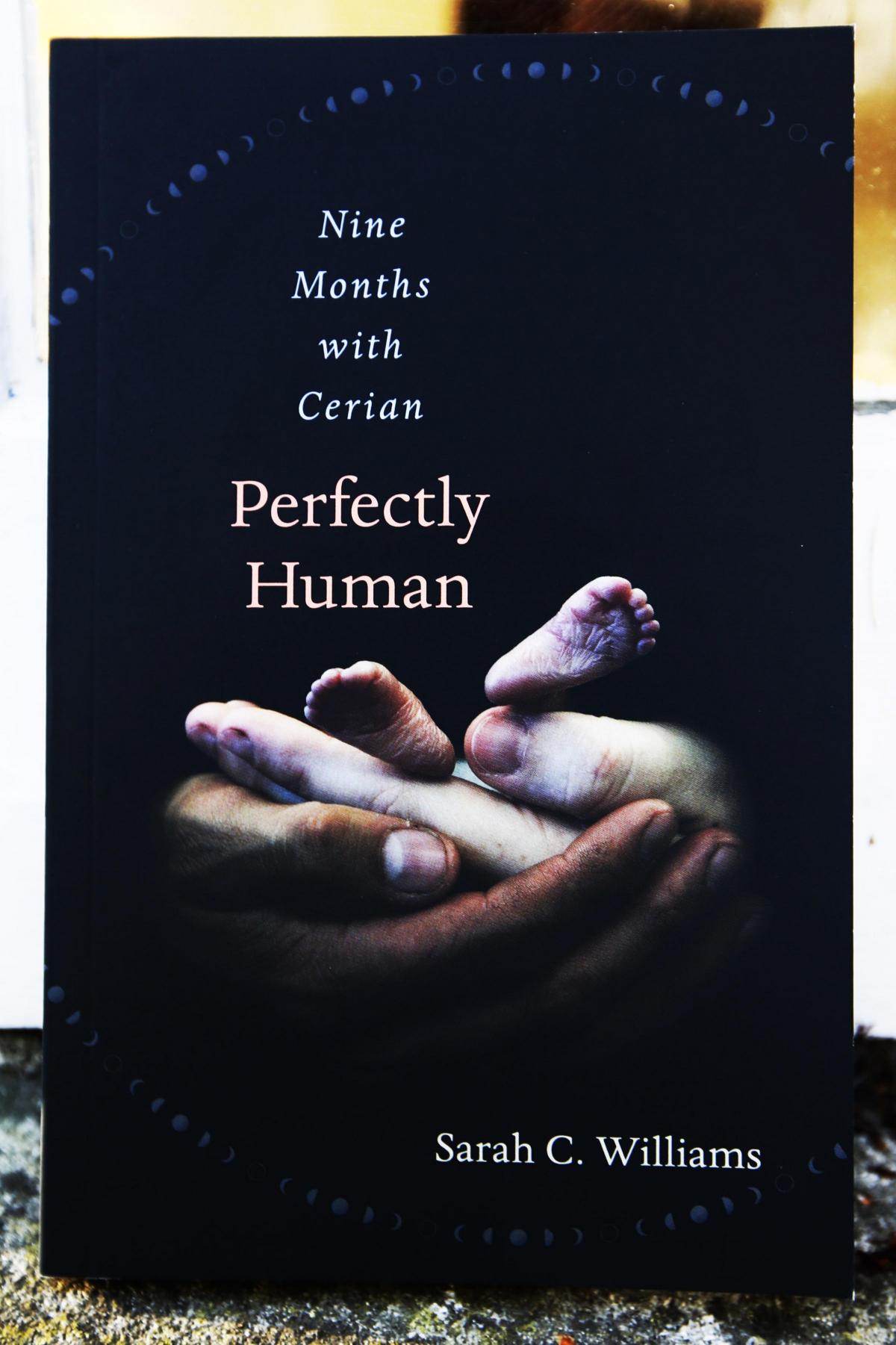

The college professor has now chosen to re-release her book, Perfectly Human: Nine Months with Cerian’, which recounts the heartbreaking story as she looks to spark conversation and debate over the issue.

She said: “It’s an unbearable weight for women to carry - deciding the fate of an unborn child - in actual fact that weight is so unbearable I question whether it should be something that women should be asked to decide on in the first place.

“We felt no matter what, in the long term we wanted to be able to say we did everything we could to love the child who we had here with us.

“I had already made a connection like many mothers do and the decision we made allowed us to love the child as a person.

“Even with a one per cent chance that the child might survive, against the odds, we felt that one per cent chance was enough for us to ask if we could live with the death of that child on our conscience.”

Mrs Williams believes the practice of prenatal screening itself is framed as ‘morally neutral’, however the system she encountered when having to decide whether or not to have an abortion was ‘anything but neutral’.

She said: “It was clear that everyone expected me to have a termination.”

“Faced with the imperative of choice, I discovered very quickly that although a termination was presented in the language of choice it was the only recommended medical option and the hospital budget was weighted towards parental technologies and stem cell research not obstetric care for complicated pregnancies.

“We felt like we were in unchartered territory.”

The wider question of eugenics and policymakers seeking to unburden health systems of future costs have also been raised by Mrs Williams.

She said: “The potential of prenatal screening lies in its power to control the overall health of a population in order to better allocate scarce fiscal resources. Never before has the pressure to mitigate the long-term costs of social care been greater.”

Ultimately, however, Mrs Williams, said the issue revolves around the question ‘what does it mean to be human?

She said: “I’m raising the question what do we really mean when we talk about a ‘normal baby’ or an ‘abnormal baby’.

She added: “Since the 1967 defining of the legality of termination we have almost as a culture created a distancing mechanism based on when we believe life starts.

“We are not helping ourselves as a culture by not finding more nuanced language to talk about it.”

The new edition of Perfectly Human: Nine Months with Cerian is available now.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel