My search for the lost Beechey boys started with a small brown case found in a dusty attic and crammed with hundreds of letters written from the trenches.

There were eight brothers, the sons of an English country parson who gloried in the name of the Rev Prince William Thomas Beechey.

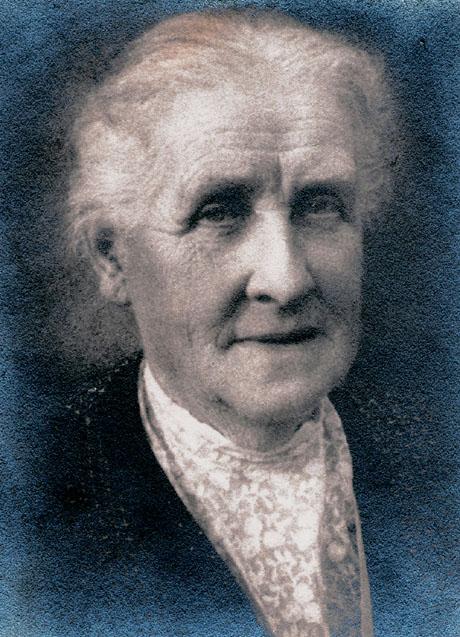

In 1918, their widowed mother, Amy, was presented to King George V and thanked for her sacrifice. It wasn't enough to prevent her youngest son, still just a teenager, being packed off to the Western Front to face the guns for the last three weeks of the conflict.

Even amid the carnage of the Great War it was a tragedy without parallel, one that had remained forgotten and unmarked for 90 years.

On a May bank holiday five years ago, I travelled to Devon to meet the Beechey brothers' niece. The worn leather case with rusting hinges had been rescued from her attic and lay open on the dining room table.

I picked up one of the bundles of letters, held together with rubber bands perished with age, and as the elastic disintegrated out dropped a yellowing, war-stained envelope with Killed In Action' scrawled across it.

It was the start of a quest that would take me to Australia where two of the brothers had emigrated for a new life on the land before the call to arms came.

Only after I had finished Brothers In War did I discover that the Beechey family actually had their roots much closer to home. The brothers' great grandfather, James, was a publican and farmer from Black Bourton, Oxfordshire.

His wife was Mary Collett, a Clanfield girl who bore him six children before dying at the age of 33, probably from exhaustion. In an untamed corner of St Stephen's churchyard, Clanfield, the Collett name is still visible on tombstones, one commemorating Thomas, Mary and Elizabeth, "who died in their infancy".

Huge families were a Beechey tradition. The Rev PWT Beechey's father was one of 13 children, while the rector himself went one better.

After 14 children, the frisky reverend gentleman who was 20 years older than his wife Amy, was banished to a spare bed in the coach house of their Lincolnshire rectory.

He would die of cancer in 1912, and be spared seeing his fine boys lay down their lives.

Almost 22 years separated Barnard, the eldest, from Samuel, the youngest, but it was their misfortune that they would all have to serve in the Great War.

As early as 1915, Barnard would be writing to his mother from a stinking shellhole in France: "We all wish the thing was over." It soon would be for him.

Only Christopher, then hacking out a living from the brutal bush country of Western Australia, would display the highest of motives for volunteering to fight in 1914, declaring: "For once in my life I saw duty clearly before me."

Younger brother Harold, who had joined him on the other side of the world, fretted: "I only hope the war will last long enough for me to get away so I can get a few quid."

Chris would be one of three brothers to survive, but he was a virtual cripple after being shot by a Turkish sniper at Gallipoli.

Convalescing in England, he fell in love with a hospital volunteer and married her in a rush before returning to Australia for the sake of his health - the sixth son Amy would never see again.

In 2003, I interviewed his daughter, Kathleen, at an old people's home near Sydney. She told me how her mother had stopped Chris going to the Anzac ceremonies because they upset him so much.

I lost touch with Kathleen and the home had no record of where she might have gone. I thought she must have died, but with the book published in Australia, I had a letter recently from a woman who had borrowed it from her local library.

"I am a registered nurse working in an care facility in Sydney," she wrote. "I am nursing a Mrs Kathleen Hector. I asked her what her maiden name was and she said Beechey'. I asked if her father was Chris Beechey because I'd noticed in his book Michael Walsh thanked Chris's daughter, Kathleen Hector.

"Kath is nearly blind now so I am reading the book to her. The look on her face is wonderful as she listens to the story of her brave father and his brothers."

The most poignant of all the Beechey letters was the last one Amy received from Leonard, a quiet romantic who had married in 1915, in the vain hope of avoiding conscription. He would sit amid the desolation of war and write home recalling blissful sunset walks with his wife, Annie.

Gassed and wounded at Bourlon Wood in 1917, his final message on a tiny scrap of paper said simply: "My darling mother, don't feel like doing much yet. Lots of love, Len."

It was written in a feeble, childlike hand that was enough to break Amy's heart as she saw another son's life slipping away.

In another newspaper article, I quoted the kindly words of a hospital chaplain who was with Len to the end. In response, David Hide wrote to me from Chichester: "Your story of the death of Leonard Beechey proved particularly moving for me on account of the two letters written by my father, Stanley Hide, to Mrs Beechey. They gave me a view of an aspect of his life which he kept hidden from his family."

I now have a photograph of the Rev Stanley Hide in army uniform, dog collar and wire-rimmed spectacles through which he saw enough horrors to be sickened by war. When it was over he stuffed his unopened box of service medals in an old sock drawer.

The Beechey story has touched many others. I knew Harold had left a sweetheart behind in Perth, Western Australia. In a pioneer town where men outnumbered women 11 to one, Diana Curly' Boyce promised to wait for him and was true to her word as Harold endured one horror after another. He was twice evacuated from Gallipoli with dysentery and was wounded in France: "Very lucky, nice round shrapnel through arm and chest, but did not penetrate ribs. Feel I could take it out myself with a knife," he writes from hospital.

Patched up and waiting to be sent back to the front line again, Harold admitted: "I don't think there is anyone who has been through the Hell at Pozières, or any of those little places down on the Somme, who wants to go again. I know I jolly well don't but I won't shirk the thing for all that."

He was killed by a German shell at Bullecourt, France, in April 1917, and has no known grave. Curly Boyce became Godmother to Chris's daughter Kathleen but nothing more is heard of her, after mention that she had become engaged to an elderly admirer.

Then, out of the blue, the ladies of the Western Australian Genealogical Society, sent me a copy of a death notice, dated 1957, for Diana Curly' Tonkinson née Boyce. Her son Ernie wasn't the least bit offended when I tracked him down in Albany, WA, and told him I was writing about his mum's sweetheart from the First World War!

At Stamford School in Lincolnshire, the CR Beechey Cup is still awarded for cricket. It is named after Charles, second oldest of the Beechey boys, who was a scholar and master there and was in no hurry to join up.

Handed a telegram while taking a maths class, he read it, folded it neatly and tucked it in his pocket before carrying on with the lesson. Only afterwards did he reveal it was news of a brother killed in action. Charles would not be spared and he summed up the family's agony in a heartfelt message from the front: "These last three years seem so awful to us after the 20 we spent in such peace and enjoyment, so let me now hope that we have had our share of the losses, although we are taking more than our share of the dangers."

In November, I delivered a Veterans' Day Address to 500 students and faculty members at a private school near Chicago, Illinois. Brought up on Vietnam, Pearl Harbour and Gettysburg, they were astonished at how the brothers' sacrifice had gone unmarked for so long. But in 1914-18, amid the mud and slaughter that engulfed the Beechey boys, clearly there was none of the compassion of Saving Private Ryan.

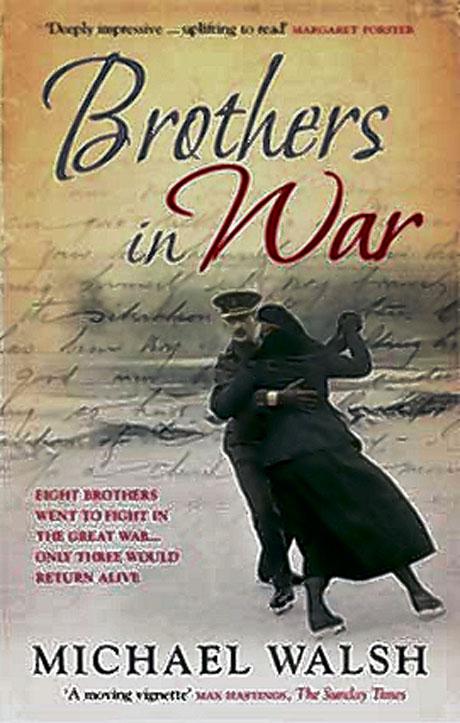

Brothers In War is published on June 7 by Ebury Press at £7.99 and in hardback and as a three-CD abridged audio set.

Roll of honor - Sergeant Barnard Reeve Beechey, 2nd Battalion the Lincolnshire Regiment, killed in action September 25, 1915, aged 38. No known grave. Commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial, Hainaut, Belgium.

- Second Lieutenant Frank Collett Reeve Beechey, 13th Battalion the East Yorkshire Regiment, died of wounds November 14, 1916, aged 30. Buried at Warlincourte Halte British Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France.

- Lance Corporal Harold Reeve Beechey, 48th Battalion Australian Imperial Force, killed in action April 10, 1917, aged 26. No known grave. Commemorated on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial, Somme, France.

- Private Charles Reeve Beechey, 25th Battalion Royal Fusiliers, died of wounds October 20, 1917, aged 39. Buried at Dar Es Salaam War Cemetery, Tanzania, Africa.

- Rifleman Leonard Reeve Beechey, 18th Battalion the London Regiment (London Irish Rifles), died of wounds December 29, 1917, aged 36. Buried at St Sever Cemetery Extension, Rouen, France.

- 2nd Lieutenant Samuel St Vincent Reeve Beechey, Royal Artillery, and Corporal Eric Reeve Beechey, Royal Army Medical Corps, both survived as did Private Christopher William Reeve Beechey, 4th Field Ambulance, Australian Imperial Force, who was discharged as a permanent invalid after being wounded at Gallipoli.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article