The Australian musician Chris Latham travelled to Oxford last week in a pilgrimage to one of his country’s most romantic war heroes.

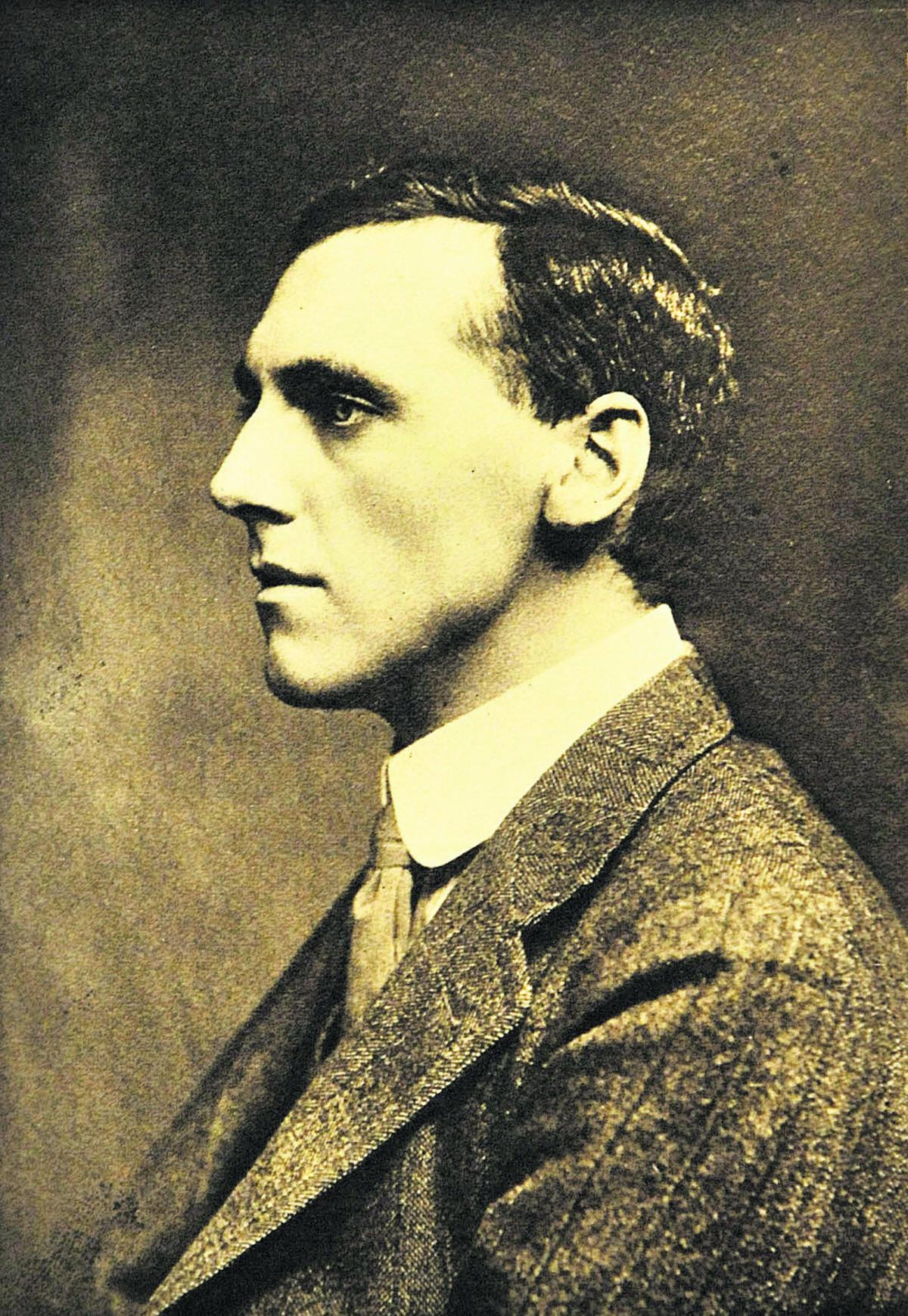

Frederick Septimus Kelly, who died attacking a German machine gun emplacement in the last days of the Somme campaign, was one of the most talented oarsmen to take to the river at Oxford, winning a gold medal in the 1908 Olympics.

But more than that, he was a brilliant musician and composer, who continued to write music of remarkable beauty even as he sat in the squalor of trenches, with death and the thunder of war all around him.

Kelly, who came from Australia to study at Eton and later Balliol College, Oxford, even produced a violin sonata during rare moments of peace that he somehow managed to find during the Battle of Gallipoli, where so many of his countrymen were to perish.

It was written for the beautiful Hungarian violinist, Jelly D’Aranyi, whom he had met when she was 16, and had played music with regularly, before going to war.

He had turned his attention to the sonata shortly after producing a memorable elegy to his friend the poet Rupert Brooke, who died of blood poisoning shortly before the battle began.

“It is all there in my head but not yet on paper,” he had written to D’Aranyi. “You must not expect shell and rifle fire in it! It is rather a contrast to all that, being somewhat idyllic.”

D’Aranyi, who never married and kept his photograph on her piano for the rest of her life, would perform it at Kelly’s memorial service. But the piece disappeared and was to become known as Kelly’s Lost Sonata.

Mr Latham’s interest in the Gallipoli campaign and love of Kelly’s music, with all the heartbreaking stories surrounding it, persuaded the Australian to go in search of a piece of music that had been missing for some 80 years.

The hunt was to involve the celebrated violinist and director of the Canberra International Music Festival in years of detective work and a hunt across Europe, before he finally uncovered the Lost Sonata, written in Kelly’s own hand, in a house in Florence.

Mr Latham spoke of his discovery, which has reawakened interest in Kelly back in Australia, during a visit to Balliol and to the college’s historic collections centre in St Cross Church, where he was able to view Kelly’s oars.

He had first read about the sonata in Kelly’s recently discovered diaries, which form part of an impressive Kelly archive held in Australia’s National Library.

Mr Latham said: “When I realised it was not in the archive, I thought ‘who might still have it?’. He had written it for D’Aranyi. She had played it and I thought she must have held on to it. It was then a question of finding her or those who responsible for her estate.”

After investigating the family tree, he eventually unearthed D’Aranyi’s grand-niece through Facebook. It emerged she lived in Florence and had inherited the manuscript.

“It looked surprisingly new and was really well preserved, written in Kelly’s own hand,” recalled Mr Latham. “There had been three versions, this was the second, the fair copy he had made. I certainly did not expect it to be such a good piece. It’s actually beautiful.

“With music written in the trenches, it is not like the war poets. Musicians often served as stretcher bearers. But they wrote happy, optimistic, life-affirming pieces. Composing music was an act of transcendence, to transport them out of the mud.”

Mr Latham returned home to Australia with a copy and performed the piece at a music festival. He is now hoping to oversee more performances at a major Kelly retrospective, entitled Music and War.

Born in Sydney in 1881, Kelly came to Oxford on a musical scholarship, going on to become president of the university’s musical club. But at Balliol, Mr Latham was made fully aware of the musician’s place in Oxfordshire’s sports history.

While in Oxfordshire, Kelly won the Diamond Sculls at Henley in 1902, 1903 and 1905, in the last setting a record that stood until 1938. He rowed in the four seat for Oxford against Cambridge in the 1903 Boat Race and in 1908 competed in the London Olympic Games, winning gold in the eights.

It was to be the last time he competed in a rowing boat, giving up the sport to become a composer and concert pianist, making his debut in Sydney in 1911 and in London in 1912.

Kelly, who set up home with his sister at Bisham, near Marlow, joined the Royal Naval Division soon after the outbreak of war and was involved in the unsuccessful defence of Antwerp. The following year he sailed for the Dardanelles with the Hood Battalion along with such scholar-soldiers as Rupert Brooke, Arthur Asquith and Patrick Shaw-Stewart, who were quickly collectively christened on the ship as the ‘Latin Club’.

While recovering from wounds at Gallipoli, he wrote the poignant Elegy for String Orchestra, in memory of Brooke whose burial on Skyros he had attended. Promoted to lieutenant, Kelly was among the last to leave and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for conspicuous gallantry there. He was to survive the Gallipoli slaughter only to die before a machine gun at Beaucourt-sur-l’Ancre, aged 35, on November 13, 1916.

Only now is his music receiving proper recognition in the country of his birth. It would be fitting, indeed, if events in Oxford to mark the 100th anniversary of the Great War were to include the music of Frederick Kelly, with the fallen here remembered with the return home of the Lost Sonata.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article