On a sunny Sunday in July 1976 — a day similar in many respects to the Sunday just passed — I first made the acquaintance of the remarkable John Otway. The location was the Boot, Stonesfield, a pub that will never be forgotten by those privileged to have known it and its hosts, John and Marian Leaves. The occasion was a Christmas party. In July? They did things that way at the Boot.

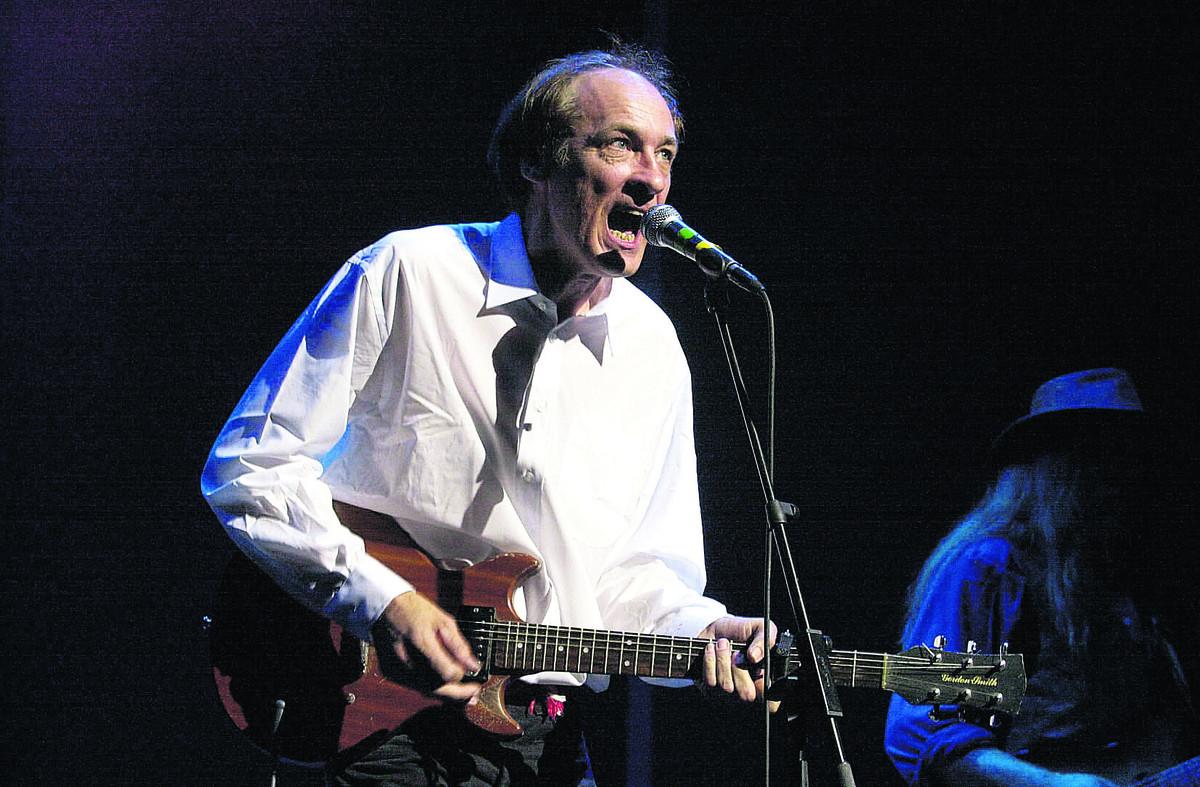

One after the other came the songs that Otway aficionados were to consider trademark in the decades to come of John’s ‘stardom’, in his unique take on this status. I recall, in particular, his trio of covers in which he successively murdered Donovan’s The Alamo, The Animals’ House of the Rising Sun and Bob Lind’s Cheryl’s Goin’ Home.

Memorably present, too, was Louisa on a Horse, which Otway and Wild Willy Barrett — also memorably present — had just recorded with producer Pete Townshend of The Who. This was not to prove the passport to the sort of conventional fame that Townshend had earlier achieved with Something in the Air for Thunderclap Newman, albeit that they were one hit wonders.

No, chart success for Otway had to wait until his third single Cor Baby That’s Really Free which, aided by the singer’s spectacularly shambolic appearance on The Old Grey Whistle Test, reached No 27 in the charts in late 1977.

It began to look as if Otway, too, was destined to chart but once. But then, in 2002, after further decades of tireless touring — with regular dates for his solid base of fans in Oxford — Otway had a second success with Bunsen Burner. As a present for his 50th birthday, admirers cleverly contrived to buy the single into the charts through multiple purchase in key places. (I still possess five copies of the disc, never played since.) The ruse worked. The record reached No 9, and Otway was on Top of the Pops.

The story of both hits naturally occupies a prominent place in Rock and Roll’s Greatest Failure: Otway the Movie, a feature length documentary from director Steve Barker. Premiered at the Leicester Square Odeon (where else?), the film was later screened at Cannes and is now being shown at venues around the country.

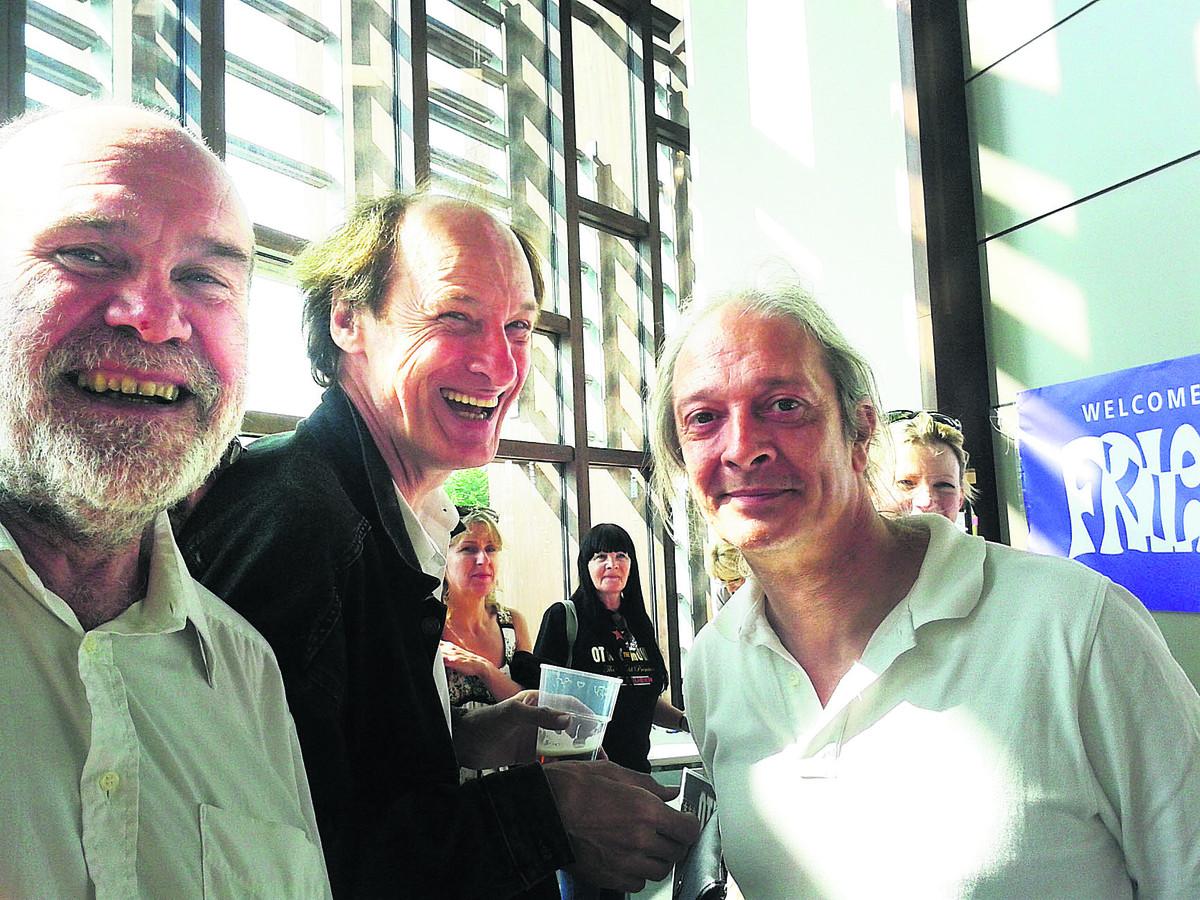

The tour began with two screenings on Sunday — in the presence of the star — at the Aylesbury Waterside theatre, an appropriate venue for a man who is that town’s most famous export since ducks. Packed into both were many who had known Otway during the days of his translation from dustbin man to rock musician. Did I not also see his mother? She is memorably quoted on screen voicing the opinion that his complete lack of a singing voice ought to have precluded any ambition for fame as a vocalist.

Promoter Paul Clerehugh (mine host at the Crooked Billet, Stoke Row) is blunt on screen too (in the nicest way) concerning Otway’s appearance at the Royal Albert Hall singing The Highwayman with backing by the Aylesbury youth orchestra of which he was once a member. This was not a version of Jimmy Webb’s country classic of that name but an idiosyncratic Otway take on the Alfred Noyes poem featuring Bess, the landlord’s daughter. “That Otway has no musical talent,” says Paul, “becomes glaringly apparent.”

Kinder comments on our hero come from, among others, disc jockeys Johnnie Walker and Bob Harris, the principal witness — along with five million viewers —to Otway’s Whistle Test pratfalls.

Some old Otway mates I spoke to would have liked more about the early days. Myself, I would have welcomed mention of his many appearances (in between the likes of Billy Idol and the Clash) at Oxford’s Oranges and Lemons (now the Angel and Greyhound) where Leaf and Marian went after the Boot. Simultaneously, he was proving a top attraction for the rock aristocracy — Led Zeppelin were regulars — with a Thursday night residency at London’s Speakeasy club. There I witnessed, at close hand, a confrontation between Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols and the aforementioned Pete Townshend (“We did it first!”) that has gone down in rock history.

Otway the Movie will be shown at Oxford’s Phoenix Picturehouse shortly, on a date still to be fixed.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article