As modelling work in Irkutsk is hard to come by, Katja pays the bills by cutting hair.

“It’s sad but true,” she said to me as she trimmed my beard in my hotel’s salon. “The women out here are all beautiful. But not the men. The men are smart, but not pretty. But it’s what we’ve needed to survive.”

Over time, Irkutsk has had many guises. A caravanserai in the early intercontinental fur trade. A launching point for scientific explorations to eastern Siberia. A destination for the 14 million Russians exiled by the gulag to forced labour camps between 1929 and 1953. And, for me, the only property in childhood games of Risk with a more exotic place name than Kamchatka.

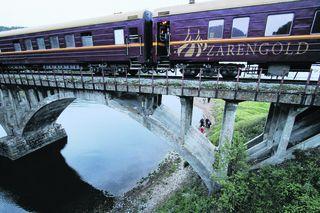

I was halfway through a journey traversing half the world by train. The Trans-Siberian had long remained a pipe dream for me until I decided last summer to take the trip of a lifetime. And so, on a warm July evening at 7.33pm, I climbed on to a 22-carriage locomotive and watched as the hawkers of the bustling Beijing Railway Station faded into the distance. My dacha on wheels was the Tsar’s Gold, a private magic carpet of a train with 44 attendants, six chefs, scores of guides, waiters and engineers, along with those three incontrovertible necessities for long-distance overland travel: a doctor, a librarian and an accordion player (yes, I was slumming it).

From Beijing, we traversed the Gobi desert overnight, crossing into Mongolia at the flatlining ex-oil town of Erlian. On board, meanwhile, there was plenty going on: Russian classes, vodka and caviar tasting sessions and – once we reached Siberia – a mesmerising on-board concert of Buryat throat singers.

That this railroad even exists at all is something of a miracle. Completed in 1916 at a cost of 1.4 trillion gold roubles – more than half a quadrillion pounds in today’s money – the world’s longest continuous train route was built by bands of labourers who suffered floods, cholera, anthrax, bubonic plague, landslides, bandits and tigers to complete it. Even the short stretch of Rail that skirts Lake Baikal required the construction of some 200 bridges and 33 tunnels.

We got to know these tracks intimately when we stopped and spent a day barbecuing and dancing alongside them at Lake Baikal. A case of vodka was opened. Bottles were passed around. The accordionist serenaded Spanish women with Russian folk songs. German couples shimmied around the samovar. Not for nothing is Baikal the stuff of legends. One Russian I spoke to told me that when she travels abroad, there are two things she misses: her mother and Lake Baikal.

From Baikal, we ventured west through the taiga, Russia’s coniferous forest, a landmass more than twice the size of the Amazon that is home to nothing but birch trees – branch after slender white branch that zoomed by our windows for days on end. Considered sacred flora in this part of the world, birch is the national tree of Russia and is used as a shamanic gateway for ancestral spirits in traditional Buryat ceremonies.

The repetitive scenery of the Siberian wilderness allowed for a retreat back into the self-indulgence of train travel. I spent some time leafing through the novels and history books at the train’s makeshift English-language library before settling on a DVD of Doctor Zhivago. It did not escape me that at no point had anyone deigned to take out War and Peace. But when you’ve booked yourself on a two-week train ride, there is no guilt in watching a little TV.

With the compass set towards Moscow, we traversed the Ural Mountains on to the European continent, speeding past rivers, lakes and remote villages with painted wooden houses. In Ekaterinburg, we paused in silence as Russian tourists wept over the graves of Tsar Nicholas and his family, executed in 1918 and now venerated as Russian Orthodox saints by much of the country. A day later we strolled the streets of Kazan, where we gawked at the city’s huge aquamarine mosque before dancing at a Tartar wedding in the mosque’s parking lot.

And then, 4,735 miles after leaving Beijing, we arrived at Kazansky Vokzal, Moscow’s gargantuan eastern railway station and a place where just a few weeks earlier, Jean Paul Gaultier had staged a titanic fashion show. Our journey had lasted just 15 days, but it felt like I had lived a lifetime on board. I stepped off the Tsar’s Gold for the last time and met Natalia, our governessy guide to the Russian capital and a woman whose diction and phraseology suggested she had learned to speak from a 1930s-era copy of English for The Soviet Scientist.

As I left the station, I gazed up to the large schedule board of trains – a swirl of red blinking Cyrillic cities, track numbers and departure times.

Later that evening, as I strolled the cobblestones of Red Square, where St Basil’s Cathedral and the GUM department store were aglow with light, I thought back several thousand kilometres to Irkutsk. I imagined the beautifully-sculpted face of Katja, heavy in concentration as she trimmed another man’s beard. I doubted she would remember me. But perhaps, as a wise friend once said, unrequited love – like lake swimming, caviar and throat singing – is a necessary companion on long train journeys.

GETTING THERE

* RAILBOOKERS offers custom-tailored, private trips on rail holidays in Europe and classic rail journeys across the world. The Tsar’s Gold Trans-Siberian journey operates several times a year between Beijing and Moscow via Mongolia (also reverse direction). There are still cabins available for various departures between May and September 2011 and 2012. The lead-in price is £3,295 per person, based on a standard four-berth cabin, and £4,495 per person based on a two-berth cabin.

For more information, call 020 3327 2438, or visit the website railbookers.com * British Airways (ba.com, 0844 493 0787) flies direct to both Beijing and Moscow from London Heathrow.

STAYING THERE

* In Beijing, the Kempinski Hotel Beijing Lufthansa Center (kempinski.com/beijing; +86 10 6465 3388) offers spacious, plush rooms (from RMB920, or £87) with access to a rooftop pool and half a dozen restaurants, including a Bavarian bräuerei.

* The Hotel Baltschug Kempinski Moscow (kempinski.com/moscow; +7 495 287 2000) is the city’s premiere luxury hotel, with 230 opulent rooms (from RUB7,920, or £167) offering every possible amenity and views straight to St Basil’s and the Kremlin. There is also an excellent Russian restaurant and jazz bar, as well as round-the-clock VIP car service.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article