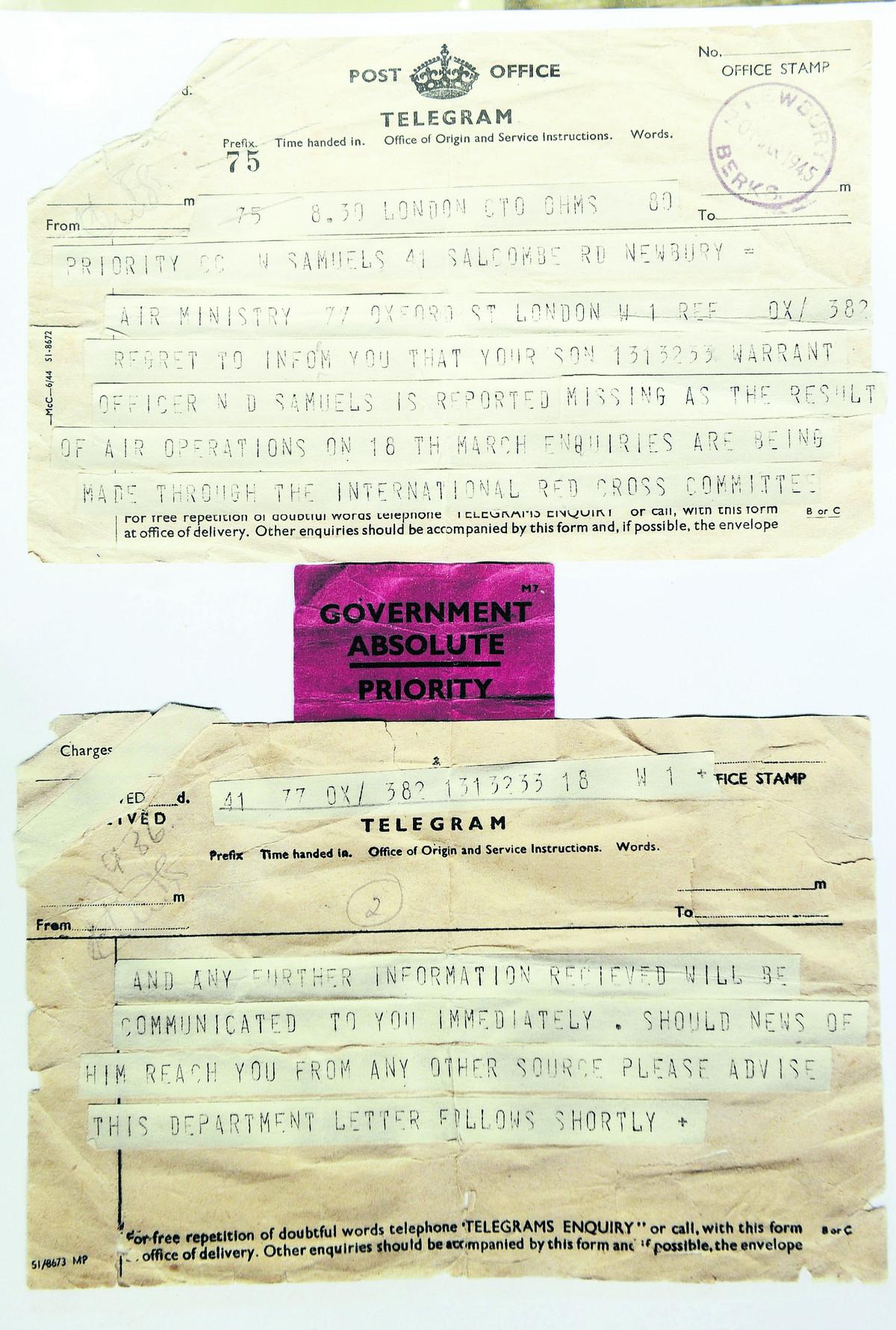

FLORENCE Samuels screamed loud enough to rattle windows when she was handed the telegram saying her son was missing, presumed dead.

It was the anguish of a mother who had lost her son at war, but in fact Warrant Officer Norman Samuels was busy ducking the enemy along the Baltic coast in 1945 after being shot down.

After weeks of evading capture, scavenging for survival, the Typhoon pilot was eventually snared.

Tired, weak and hungry, he was taken to Stalag Luft I, a Second World War prisoner of war (PoW) camp near Barth, Germany.

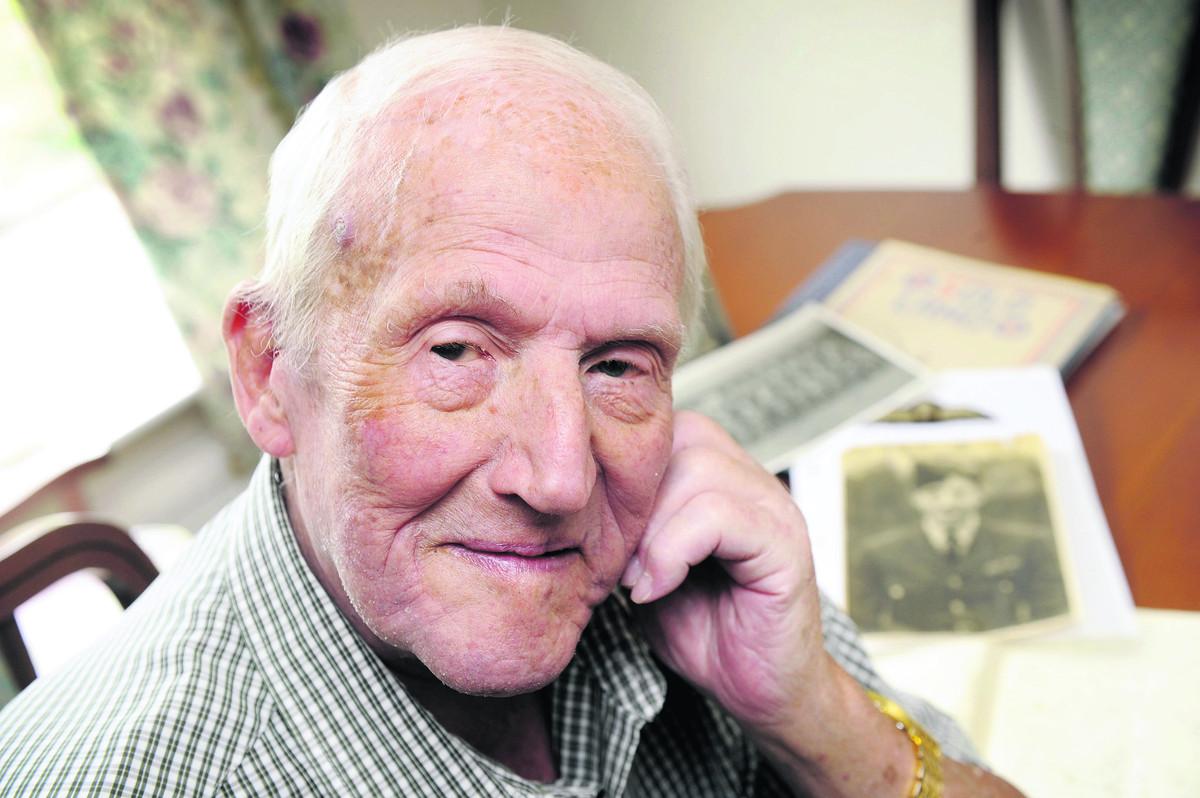

Now 91, the war hero who now lives in Abingdon with wife Barbara, has recounted his time flying the top planes of the day, and how he survived where many of friends died.

He came forward after an appeal in the Oxford Mail to gather stories of PoWs for the Soldiers of Oxfordshire Museum being built in Woodstock.

Mr Samuels was born in Newbury in 1921 and grew up in the West Berkshire market town.

In 1940, aged 19, he joined the Royal Air Force Oxford University Air Squadron.

At that time the UK had no place for trainee pilots. So, after six weeks of basic training he was sent to America to learn to fly under the Arnold Scheme, a training programme run by United States Army Air Corps General “Hap” Arnold.

Under this tutelage he quickly became an elite pilot.

In 1941, at ease in the cockpit of almost any flying machine, he says, he was sent back to the UK.

He said: “I joined 193 Squadron in Devon, and that was where I met my future wife, Barbara Lean, on Christmas Day 1942.

“A Spitfire squadron had lost six of its 12 pilots in one day, so they moved us across to 610 Squadron.

“They were marvellous planes to fly, and I enjoyed every moment. We had Spitfire MkVs then - they weren’t fast enough for war really at that time.

“We cleaned them with car polish, and that gave us an extra 5mph, then they clipped the wings and that gave us another 5mph.

“Of course we were still 100mph short of the Germans’ speeds, but what could you do?”

He helped defend London, and fought over Beachy Head, but with losses elsewhere he was drafted back to 193 Squadron, which was by now in Antwerp, Belgium, in 1944.

After surviving the ill-fated Battle of Arnhem in Holland in September, 1944, his luck ran out in a Typhoon near the same town in 1945, just weeks before the end of the war.

He said: “It was the last push by the Germans and on March 18 I was shot down.

“I’d already fought in the Battle of Arnhem, when we suffered heavy losses. Going back, I wasn’t so lucky.”

He continued: “I didn’t have time to think if I was going to die. I must have been knocked out clean by my gun sight. I’d put rubber on it because I was always hitting it with my hand.

“I’d seen men die in crashes; they hit their head and it killed them.

“The rubber must have saved my life. To be honest looking back I should have died many times over.

“I ended up walking through Germany, got on a train, and that was bombed by the Allies.

“I walked and walked, right up to the Baltic Rhine, I scavenged for food and did what I could to survive.

“It was a long time between being shot down and being captured.

“Every day was ‘live or die’.”

The Germans eventually caught up with him and sent him to Stalag Luft I, a camp filled with about 9,000 PoWs.

He said: “I had lost weight by the time I arrived, and we didn’t have a lot of food. I remember a battle with a Welshman who kept stealing my bread.

“Luckily I was only there a few weeks before we were liberated, by the Americans, on my wife’s birthday, April 30, 1945.

“I started the war with the Americans, and finished it with the Americans.”

After the war he worked as an engineer for the Southern Electricity Board.

The couple, who have been married for 67 years, moved to Abingdon and had one son, Peter.

Peter, 62, and also living in Abingdon, said: “We are all hugely proud of Norman for what he did, and love him dearly.”

Mr Samuels wrote his experiences down in a book for his family.

He said: “It was a very different world then to what it is today.

“It wasn’t personal; I killed Germans, and saw my friends killed. But I never held any grudges. I was a young man sent to fight and that is what I did.

“At the time the Government had sent another telegram to my mother, this one said if I didn’t appear that day, that would be the end of it.

“Luckily there was a distraction as she was heading to church and she never got it, I think it might have finished her off.”

And his mother? She lived to 100, and when her son came home she screamed again. This time with delight.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel