OXFORDSHIRE escaped the worst of the effects of the 1926 General Strike.

Our sister paper, The Oxford Times (the first edition of the Oxford Mail didn’t appear until 1928), was upbeat in its assessment of its impact on Thursday, May 6, though there had been violence and arrests in other parts of the country.

The strike by 1½m railwaymen, dockers, printers, steelworkers, power workers, building workers and gasmen lasted nine days, from May 4 to 13, and was called by the Trades Union Congress.

The aim was to force the Government to act to prevent wage cuts and worsening conditions for 800,000 locked-out coalminers.

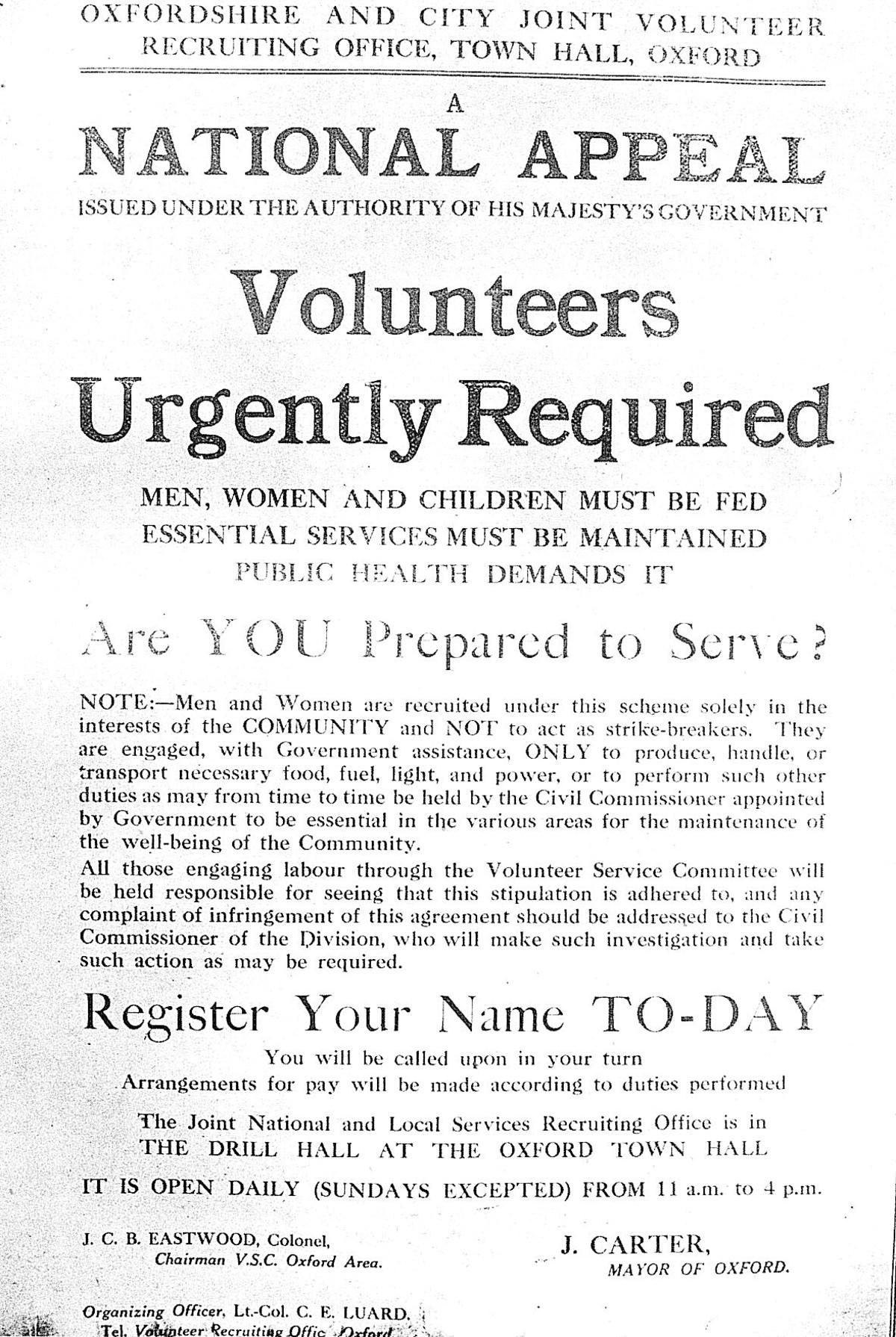

Volunteers were quick to answer a Government appeal to keep vital services running. When Colonel Luard, in charge of recruitment, arrived at his office in the drill hall at Oxford Town Hall at 9am on May 4, crowds were waiting to sign on.

The Oxford Times reported: “The Drill Hall was a hive of industry, the recruiting of volunteers in order to keep up essential services proceeding at a rapid pace. Scores of willing helpers are giving their assistance in the clerical work involved. All day, there was a stream of people, young and old, offering their services in any capacity.”

A total of 3,142 people volunteered, 1,373 from the city, 1,769 from the county and 1,870 undergraduates. In the event, only undergraduates were deployed, with nearly 1,000 of them going off to jobs in other parts of the country.

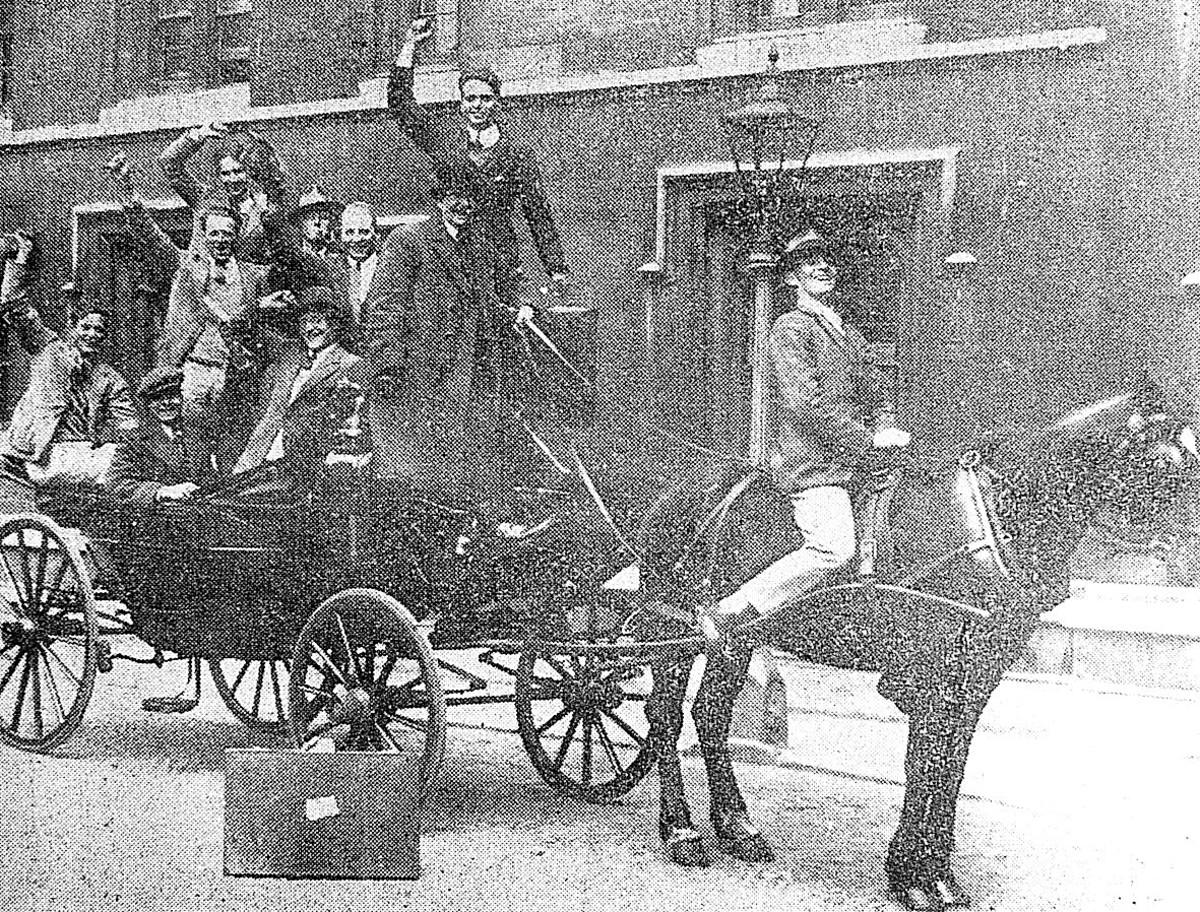

Seats were provided outside the Town Hall and post office in St Aldate’s and they sat with their suitcases until cars could be commandeered to take them to their destination.

Some played halfpenny nap using their suitcases as tables and were promptly told by a policeman that playing nap in the open was illegal.

Cheers were given as each vehicle stopped and took away a band of volunteers. One driver who said he was going to Scarborough, was told as three undergraduates got in: “Drop these men at Hull.”

One student whose car broke down outside Hull told later how a menacing crowd had fired marbles from catapults at him. “What amazed us,” he said, “was the accuracy with which some of the filthy mob spat at us at six yards’ range.”

There was some local support for the strikers. At a meeting in St Giles, Oliver Baldwin, son of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, said if the unions were smashed, it would mean longer hours and lower wages for everyone.

A group of women students boarded a bus in St Margaret’s Road and tried to persuade the driver and conductor to go on strike, calling them ‘blacklegs’ and ‘rotters’ when they refused.

But the strike gradually fizzled out. Although the miners stayed on strike, others drifted back to work.

The Government’s recruitment of special constables, volunteers and troops and the grin-and-bear-it spirit of the British people had won the day.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here