How pioneering industrialist William Morris transformed Oxford’s public transport.

Of all the great benefactors who have endowed Oxford and Oxfordshire with money one stands alone for the sheer scale of his generosity — Lord Nuffield.

His home at Nuffield Place, off the Oxford-Henley road, gives a unique insight into the unassuming way of life of this extraordinary man and his wife. It also preserves a slice of the 1930s.

There is the story of how a motorist stopped to chat one day while Lord Nuffield was clipping the hedge. The motorist asked him what sort of a chap Lord Nuffield was.

“Oh, he is not so bad when you get to know him,” he replied.

Was he paid well?

“It is enough and there is some left over for others.”

The stranger then proceeded to tip him half a crown!

William Morris, later to become Viscount Nuffield, was born in Worcester in 1877 but moved to Oxford when he was three. He started in business aged 16 with £4 capital, making and repairing bicycles in James Street, Oxford.

He then went on to found a car manufacturing empire which, at its height, employed 30,000 people in Cowley.

But few realise that before turning his attention to motor cars he was not such a mild-mannered young man. And he concentrated on motor buses — much to the consternation of Oxford city councillors. Anyone moaning that there are too many buses clogging up Oxford’s city centre streets today should spare a thought for their predecessors of 1913.

In August that year there was no public transport in Oxford at all — thanks to the extraordinary antics of William Morris and the future MP and editor of the Oxford Mail, Frank Gray.

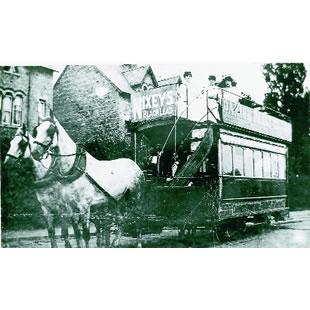

For some decades horse-drawn trams, trundling along tracks, sunken into the surfaces of St Giles and the Woodstock Road, had been in daily use. Then the drivers went on strike over 6d (2.5p) a day and the two colourful Oxford entrepreneurs decided that it was time Oxford’s transport was upgraded.

Some say that the trams, one of which was until recently seeing active service as a chicken coop in Yarnton, only survived as long as they did because they were remembered with such nostalgic fondness by generations of former undergraduates.

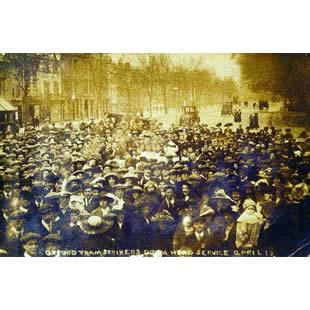

Be that as it may, there was nothing sentimental about the derision with which the town (as opposed to gown) viewed the trams, or the way in which Gray and Morris stirred up popular feeling by putting a couple of motor buses on the streets without a licence.

Only a small proportion of the crowd, which alternately jeered a poor old horse and its tram and cheered the motor bus, was able to board the first bus bound for the city centre.

A dignified policeman calmed the situation down by declaring that he hoped no force would be necessary but he noted that: “You [Gray] and Mr Morris take full responsibility for this breach of the law and anything which may result.”

Amazingly, the two then called a mass meeting at which the behaviour of the populace so cowed the authorities — they tried to torch a horse-drawn tram — that the corporation (the predecessor of Oxford City Council) gave in.

That same year over at the Gown, as opposed to Town side of Oxford, Edward VIII, when Prince of Wales, seems to have been enjoying a happier time at Oxford than that endured by his grandfather, Edward VII.

He wrote in his autobiography: “From my point of view, as a human being, the easy conditions under which I took up residence at Oxford in October 1912 were a vast improvement over those laid down by the Prince Consort for my grandfather some 50 years before.”

Instead of living apart from other Christ Church undergraduates in a rented house, with fellow students expected to stand up respectfully every time he attended a lecture, the future Duke of Windsor lived in rooms at Magdalen College.

However, he points out in his book, A King’s Story: “The Socialist son of a miner who might sit beside me at lectures would scarcely have agreed that I entirely shared the common lot.”

For instance, the student prince was given the first private undergraduate bathroom at an Oxford college and his rooms were specially redecorated for him. In addition, he was attended by a personal tutor, a valet and an equerry.

Looking back at this recent century of wars and economic expansion, the greatest changes for Oxfordshire seem to have sprung from centralisation on the county town.

The huge industry at Cowley, making the very machines that allowed people to commute ever further, prospered, but the older rural industries centred on villages and smaller towns died — slates from Stonesfield, gloves from Woodstock, plush from Shutford.

Indeed, all the moving about we do these days is probably the aspect of early 21st-century life that would most astonish a time-traveller from the rural Oxfordshire of 100 years ago.

We all know about glove-making at Woodstock. The Queen was presented with a pair by the town’s mayor in 1957, just as Elizabeth I had been some 400 years before. Less well known is Woodstock’s metalworking trade.

The last Woodstock metalworker, whose shop closed down about 100 years ago, displayed in his window a Royal Warrant for steel-making, granted to his ancestor by Queen Anne.

The industry consisted of making polished objects out of horseshoe nails. Details, such as whether the technique involved heating the nails up or working from cold, are now forgotten. Thame, too, had an industry it made its own — the manufacture of hooks and eyes, now superseded almost entirely by the zip fastener. Until the 1930s the town, like most other rural centres, also had its own brickworks.

In Shutford, near Banbury, the once flourishing business of making plush, a sort of velvet used in the liveries of footmen, or the fabric used to cover grand furniture, continued until 1944, when the last remaining hand-weaver, John Turner, retired after 53 years service.

And in Stonesfield the business of making slates came to an end when the two remaining workers had an argument about who could work the quickest. In any case, the slate-splitting process relied on sharp frosts of a kind seldom seen these days, although possibly not last winter!

Back in Oxford, where the motorworks of William Morris had in the First World War turned to armaments manufacture, the Oxford Union Society voted in 1933 “that this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and its Country” by 275 votes to 153.

Just six years later, students and townsmen were, of course, fighting the Nazis, and the Cowley works were again given over to military purposes.

Mercifully, however, Hitler spared Oxford from bombing raids, though as the war artist Paul Nash, who lived in Oxford from 1939 until his death in 1946 recorded, a corner of the Cowley works was used for storing shot-down Nazi aeroplanes.

Lord Nuffield would probably be surprised today to see how brain has taken over from brawn at the site of his factory, now largely a high-tech business park, with only a fraction of the space being used for BMW to produce the Mini — a runaway success — on clean production lines requiring very few workers compared to the tens of thousands he employed.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article