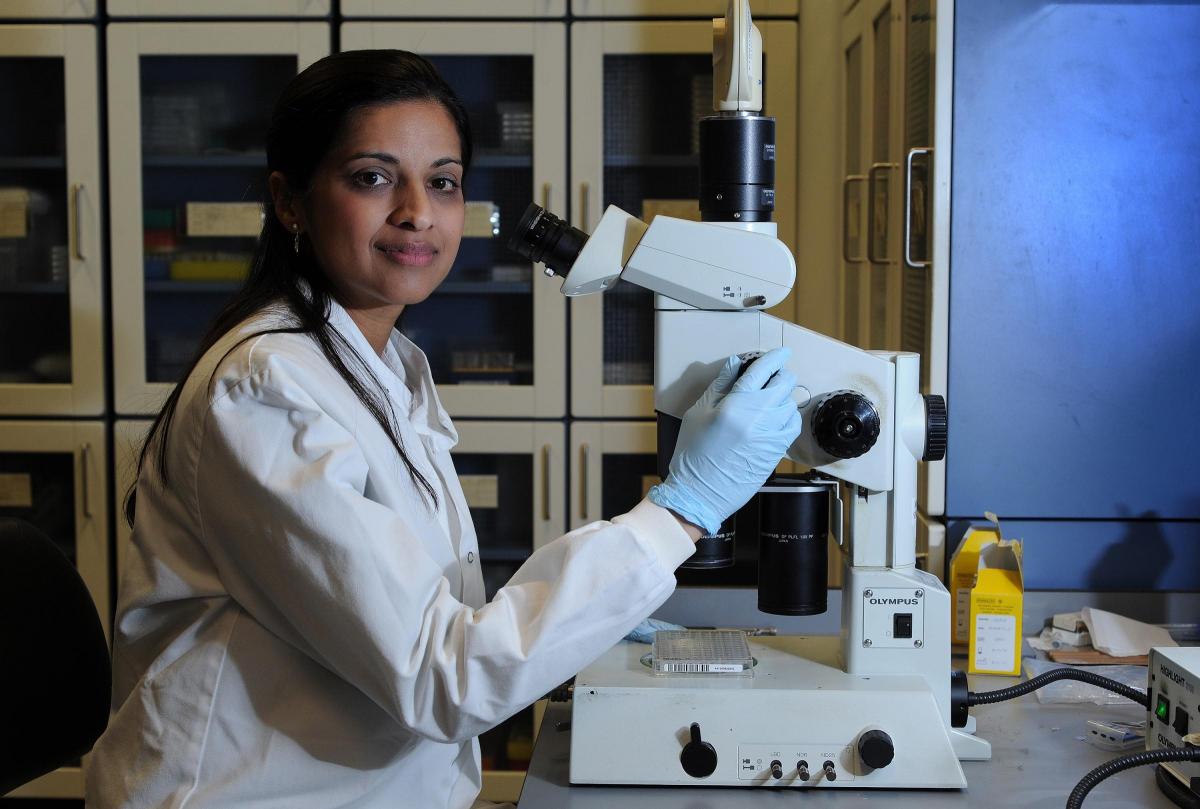

Dr Sarah Nurmohamed's experience of tragedy has turned into a personal challenge to help find a cure for cancer. Gerald Isaaman, a charity campaigner for the charity Leuka, talked to her about her work

Seeing a dear friend die from a complicated form of leukaemia despite all her efforts as a research scientist to save him has been a grim personal tragedy for Dr Sarah Nurmohamed.

The 35-year-old suffered injuries herself in a car accident in London in 2014, which put her shoulder out of socket, tore ligaments in her back and caused whiplash which has added to difficulties for her work at the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine at Oxford University.

She said: "At the time of the accident I was a Junior Research Fellow in Oxford and at a peak in my career working towards establishing my independent career in blood development and Leukaemia.

"I have always been very driven and working in the field that I do, makes me all too aware that life is short.

"After the accident, I wanted to live every moment and I found that my movement was impeded by the injuries. I worked closely with my doctors and physiotherapists to re-gain mobility.

"The best way to recover, although painful, is to stay as mobile as possible. Getting back to work so quickly has been a part of my recovery and I am driven by my ambitions to find cures for leukaemia."

The injuries only served to add to her determination to find the genetic code that causes blood cancers, which has now overtaken heart diseases as the UK's number one cause of death, one person in 25 now prone to suffer from cancer.

The research scientist has slowly taught herself over the past year to become ambidextrous and can now write and do her research equally with both hands.

This passion to return to work and help find a cure for cancer has not only aided her recovery but helped her return to a favourite pastime of ballet dancing.

Dr Nurmohamed said: "It was a very sad time for me when a friend – who was like a little brother – passed away last November. The day he died I was in hospital myself.

"He basically had an anti-drug resistant bug and I caught it myself and ended up in hospital too.”

She added: "These unique experiences like the death of my friend are invaluable for my career and re-emphasis the necessity for scientists and clinicians to work together in the search for leukaemia cures."

Dr Nurmohamed has now recovered and has spent the past months continuing her research with the help of two summer students in her laboratory, one from Russia and the other from the UK, all of which adds to the international collaboration taking place across 10 centres in the UK thanks to the funding of the London-based charity called Leuka.

Dr Nurmohamed is originally from Toronto, Canada, before moving to the UK a decade ago to complete her education at Cambridge before deciding to spend the next seven years devoted to cancer research.

She said: "My work begins with understanding blood development and aims towards understanding how the errors in the genetic code causes blood diseases, such as leukaemia, with the ultimate goal of designing cures for patients, and we are making progress."

The researcher's passion is echoed by Olive Boles, the London-based chief executive of Leuka, she said: "Finding a cure for cancer is test of endurance.

“But what Leuka is seeking is future funding to fight blood cancers through the work of inspirational scientists across the country who remarkably come from round the world to work in the UK because of its global reputation as a centre of scientific and clinical excellence.

“Their task – and mine – is dedicated to save the lives of some 20 people a day diagnosed with leukaemia a type of blood cancer. Unfortunately one in 25 people will develop some form of blood cancer in their lifetime. To do that we have to raise more funding to support our committed scientists in their amazing research to find solutions.

“It can be a frustrating struggle as some successful treatments have been found but it is then discovered that the side-effects they produce make them impossible to introduce, the cure sometimes proving worse than the disease.

“But I am dedicated to the Leuka cause, as I can empathize with those whose lives are devastated by the disease.

To donate to Leuka see leuka.org.uk/supportus/donate

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here