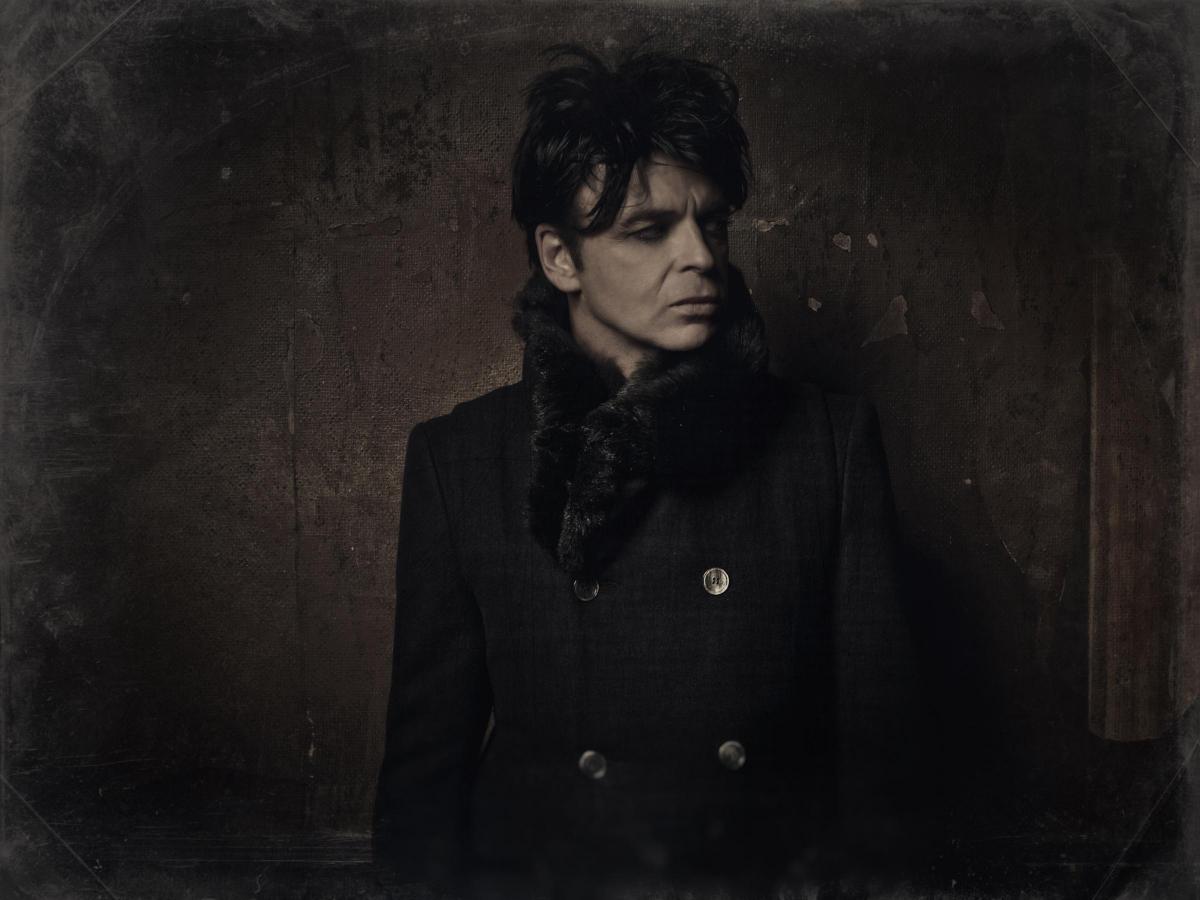

Electro pop pioneer Gary Numan is a man who lives in the future. He tells Tim Hughes why he is now taking the time to revisit some of his earliest tunes

GARY Numan, the godfather of British electro-rock, has always existed out of time.

When he burst onto an unsuspecting 70s music scene with his band Tubeway Army, he seemed other-worldly, his hard-edged music and robotic image standing in sharp relief against a background of saccharine pop, pompous prog-rock and scuzzy punk.

Four decades on and he still sounds unique and futuristic, his music alternative, dark and aggressive and sounding just as urgent as those electrifying opening synth chords on Are Friends Electric in 1979.

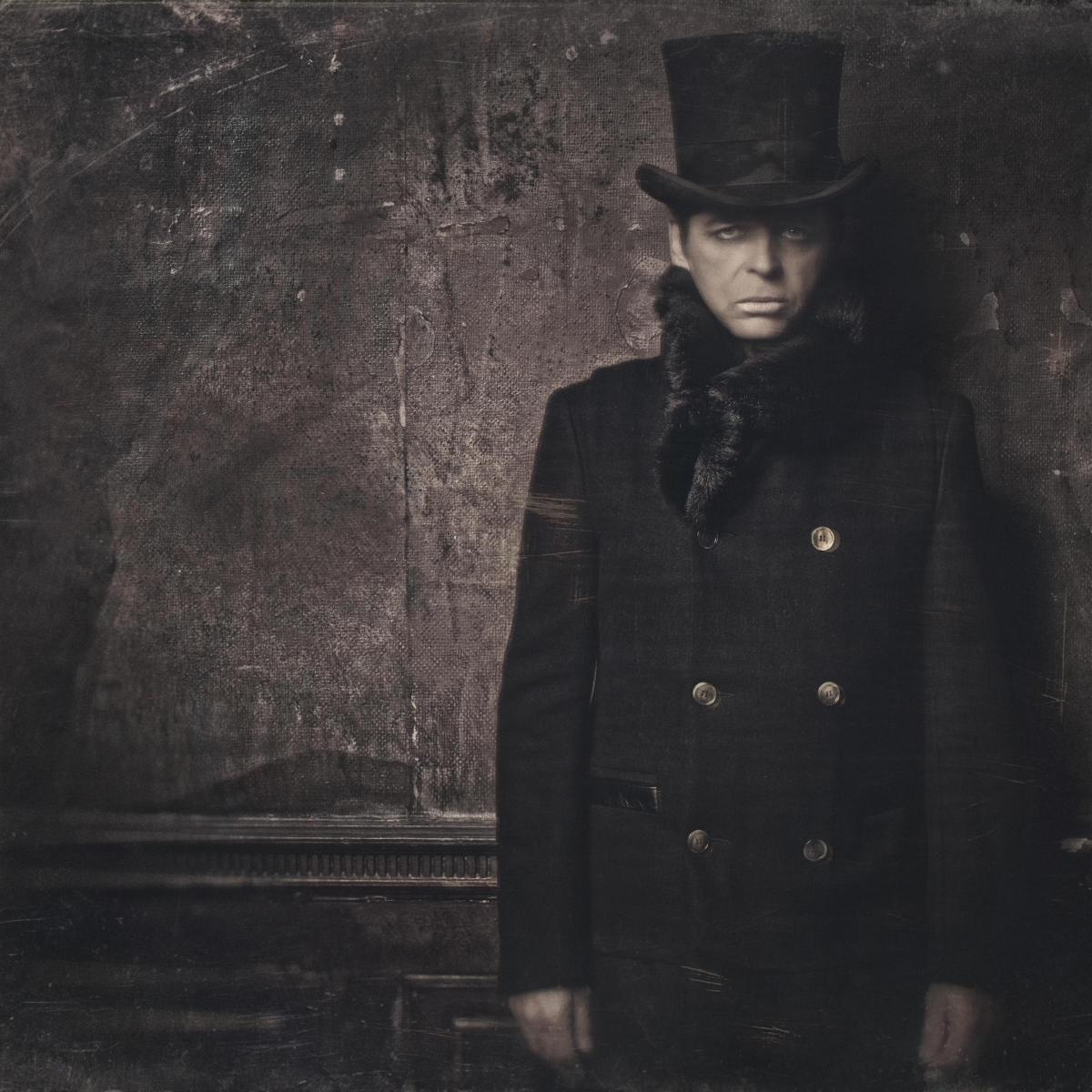

While always pushing the boundaries, fans of Gary's vintage material will be delighted to know he is not averse to revisiting his classics, and next Thursday returns to Oxford to celebrate groundbreaking albums Replicas, The Pleasure Principle and Telekon, which span his 'Machine' period between Tubeway Army and his first two solo albums.

"I don't play much old stuff normally so, as I'm between my last album and the new one coming out next year, it seemed like a good opportunity to play songs we rarely play, and a good excuse to get out on tour again in what should be a quiet songwriting period," he says.

"It's partly why my new album is late, I love touring."

He goes on: "The three albums we’re taking songs from are all from the very start of my career.

These are the albums that helped launch electronic music into the mainstream (they were all number 1 albums) and shaped much of what came later.

"My last album Splinter had the best reviews I’ve ever had, was the best selling Numan album since 1981, and so it seemed to make sense to revisit where it all started."

For a man who can't stop moving forward, it's a rare treat for fans.

"Doing old stuff is okay once in a while, like this tour, but it's always more exciting playing new songs," he says.

"Next year will see the new album out and we'll be touring the world with that one.

"I'm very excited to see that coming together."

Still, he says, it's fun revisiting that extraordinarily productive few months, between 1979 and 1980.

"Each of the three albums, although all released within a 12 month period, straddle and document my life before success, during the onslaught of it, and on to the paranoid thing it left me afterwards, for a while. So yes, it's interesting to revisit all those feelings and remember what my life was like back then, and how I was dealing with it.

"Badly for the most part."

He refers to his roller coaster career, battles against depression and financial ruin, and unkind - and undeserved - criticism. Unbeknown to himself, or anyone else, he was also living with Asperger's Syndrome – a condition only recently diagnosed.

Far from hindering him, though, he credits his Asperger's for shaping the creativity, which at one stage made him one of the country's biggest and best known artists.

"It's helped me very much," he says. "I am obsessive, which is a very useful trait in the music world.

"I am ruthlessly focused, again, a good thing in my profession. I can detach emotionally, which is very handy for reading bad reviews. I think differently, I see the world differently – which is all very useful for carving out your own unique path.

"I would never not want to have Aspergers. Not being very comfortable, or capable, socially, is a very small price to pay for all the good it brings."

The albums feature his best known tunes, among them Complex, We Are Glass, I Die: You Die – and, of course, Are Friends Electric and Cars.

Does he still enjoy playing the classic tunes, or grow tired?

"I like the reaction they get but Are Friends Electric and Cars are far from my best songs, in my opinion, so I look forward more to other moments in the set. I'm proud of them though.

"I have done gigs in the past where I left them out but I realised that was selfish, and perhaps a little arrogant. I always do those two now, be it a new album I'm promoting or not."

And he can't wait to bring them to Oxford.

"I love playing live, and travelling, so touring is perfect for me," he says.

"We've had so many great gigs in Oxford, it's become quite a favourite with me and the band."

He is assured a heroes' welcome from his loyal army of fans – or 'Numanoids'.

"I work very hard at my music but also at my relationship with the fans," he says. "I do several things, and have even more diverse things planned, that allow us to meet and share experiences.

"This week, for example, I have fans sitting in on the rehearsals every day. I want them to see and be a part of things most artists prefer to keep behind closed doors. Each year I try to think of more ways that we can interact. I think it's vital, as the music biz is rapidly evolving into a very different animal, to have a very close relationship with your supporters."

And what can we expect from the new album?

"It will be heavy, dark, aggressive and mostly electronic, and it will be late unfortunately. I now hope to have it finished by March and released in July."

It follows the release of a biopic, Android in La La Land, a candid and heartfelt look at Gary's life and career. How was it to make, I ask? And did it turn out as he hoped?

"Not quite," he says. "I thought it missed out a lot of the drama, and humour, within the stories it told. "There was so much more to be told, and chronologically it's a bit all over the place and so a lot of it doesn't make sense."

And what has the reaction been?

"People seem to like it, but that's because it isn't a bad film. It's just okay, a harmless thing. I believe it could have been a lot better."

So, as he steps back in time with his classic tour, how does he think he has changed since his early days.

"The music is obviously very different but I'm not sure I've changed that much," he says. "I'm still as insecure as ever."

And what is he most proud of?

"As an artist, that I am now considered innovative and influential; a ground breaking pioneer. That's a pretty cool and a rare position to be in for someone still very much alive.

"As a man, I'm not so sure. I still have a lot of work to do there I think. Another 42 years should do it."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here