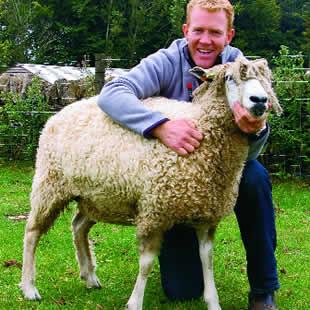

Broadcaster and farmer Adam Henson explains how Cotswold sheep have shaped the history and landscape of Oxfordshire.

Not only does the Cotswolds owe its name to a breed of sheep ‘The Hills of the Sheep Cottes’ but also their heritage and architecture. But, like all good stories, it is best to start at the beginning.

After the Romans invaded Britain in AD 45, they settled here, built communities and started farming. Like all settlers throughout history, they brought their livestock with them.

The sheep they found here were small, horned, coloured, short-tailed and naturally shed their wool — in other words, the little indigenous sheep, which have survived in our northern isles to this day.

The Romans needed quality wool and meat in large quantities, so they introduced the Roman Longwool. This was a big, white hornless sheep with a heavy lustrous fleece that did not shed.

The area of Britain most intensively settled by the Romans was the south east corner bordered by the Fosseway, which runs from Exeter to York. Here you will find all our Longwool breeds today, including the Cotswold. The high limestone grazing suited these sheep and, by medieval times, they ran these hills in their thousands. Wool was the most important product of this country and our major export.

The flock masters and wool merchants grew rich on the ‘golden fleece’ and built all our great manor houses and churches. Folklore has it that the tops of the elaborate stone tombs at St John the Baptist Church, in Burford, represent the wool bales of the Tudor fleece merchants who prospered from the sheep-nibbled hills around the town. Unfortunately for the theory, the ‘bale tombs’ date from the Restoration period — two centuries after the Cotswold wool boom.

Wealth from wool, though, unquestionably gave the parish church its current grandeur. Enriched by donations from Burford’s fleece tycoons, the building was completed in the late 1400s and its windows filled with stained glass, of which fragments remain at the top of the west and east windows.

A boom period came from 1340 to about 1540 when top-quality wool from Cotswold sheep was exported to Europe. The export of wool to the continent was a prime source of income for the Crown, as evidenced by the Lord Chancellor’s bench, called the woolsack, in the House of Lords being stuffed with Cotswold wool for several hundred years.

Wool merchants of the Cotswold market towns collected fleeces from the local farms and sold them to middlemen called Wool Staplers who held a monopoly of the trade from the Crown.

In early medieval years raw wool tended to be exported to Flanders to be turned into cloth and several kings actually issued commands forbidding such export in the hope of growing a manufacturing business in England.

Here Witney had some advantages. Firstly it had acquired skilled woolmen early when the Bishop of Winchester controlled its trade. Secondly its position by the pure waters of the Windrush made it ideal for the process of turning wool into cloth. In short, conditions were ideal for the advent of the blanketeers.

However, even during the 15th century, wars on the continent were interrupting the flow of the wool across Europe and causing a slowdown in trade.

But merchants soon began to realise that exporting manufactured cloth was going to be even more profitable than the export of raw wool. And this continued right into the 19th century as the blanket mills of Witney continued to flourish.

The export of fleece wool developed into the production of cloth and the woollen mills of the Stroud valley became famous for this, especially for Cardinal’s robes and army tunics, as the red colour was perfected here.

The decline of the Cotswold sheep began when the nation’s woollen industry moved to Lancashire during the industrial revolution, where more woollen mills could be built to use the many fast-flowing streams.

Also, British colonists had developed vast flocks of Merino sheep in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and South America. Merino wool with its short, ultra fine staple, was ideal for the market. So the Longwool breeds, with their long coarse fleeces, turned to the production of mutton to feed the overcrowded towns.

Two hundred years ago, a farmer in Leicestershire, Robert Bakewell, developed his Dishley Leicester sheep, which were so popular that his rams were used to improve all the Longwool breeds including the Cotswolds.

So the Cotswold got bigger and retained its quality fleece. Right up until the Second World War, Cotswold rams were exported to the Eastern counties to cross with their Suffolks to produce the Suffolk half-bred.

Cotswolds were a mutton breed and the castrated males were kept during their second year as theirs was the best quality fleece. They were then fattened on turnips, on which they were folded and sold as quality mutton.

By the end of the Second World War, families were much smaller and the demand for small joints of milk-fed lamb was the final death knell for the Cotswold. It declined in numbers so rapidly that by the end of the 1960s there were a mere 300 breeding ewes in just two flocks. The few members left in the breed society were struggling to keep going when in 1973, my father, Joe, helped to launch the Rare Breeds Survival Trust, as its founder chairman.

With good publicity and media support, the trust made rare breeds fashionable and helped small breed societies by offering registration facilities and breed promotion.

Today, most of the wool clip goes to individual hand-spinners or to the Cotswold Woollen Weavers at Filkins, near Lechlade, where it can be seen being made into woollens.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article